Trump & Rubio tighten the noose on Cuba

The impacts of a tightened US blockade, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the return of Trump with a vindictive Marco Rubio as Secretary of State, have deepened the crisis in Cuba, making international solidarity with the island more important than ever.

June 05, 2025 by Manolo De Los Santos

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio in a press conference. Photo: US Secretary of State / X

Cuba is once again facing a severe, multi-faceted crisis, not due to the hurricanes that pummel through the Caribbean every year, but from the relentless and suffocating pressure exerted by its powerful neighbor to the north. This is a recurring story of a people striving for independence under an unyielding siege and blockade. Through deliberate actions, the US government has been meticulously constructing and enforcing even greater barriers that threaten the very survival of the Cuban people.

The latest expression of this crisis came on May 30 with an announcement from ETECSA, Cuba’s state-owned telecommunications company, regarding a significant rate hike for mobile data. While seemingly minor to outsiders, for Cubans, it ignited a major criticism born of simmering frustrations. The new rates, particularly for additional data, are high in comparison to the average salary. An extra 3 GB now costs 3,360 Cuban pesos, nearly ten times the price of the monthly 6 GB plan. This is not merely a price adjustment; it came as a shock to the vast majority of Cuba’s 8 million mobile phone users, many of whom rely on internet access for education, work, and to connect with family abroad. This ETECSA announcement, though, is not an isolated incident; it underscores the immense strain under which Cuba attempts to meet the basic needs of its people under the US blockade.

Tightening the blockade

For those less familiar with Cuba’s recent history, the island’s economy, already reeling from the pandemic’s devastating blow to tourism and the six-decade blockade, has been further squeezed since Trump first took office. The 243 sanctions imposed by Trump during 2017-2021 remain in place, a suffocating blanket woven into the fabric of daily life. Even under President Biden, who campaigned on promises of change, the pressure was maintained.

Back in 2017, the US accused Cuba of “sonic attacks” on its embassy officials. A claim later proven false, yet it served its purpose: a pretext for Trump to freeze relations, collapsing tourism, and closing the door to the over 600,000 annual US visitors. Then came the shutdown of Western Union in 2020, disrupting vital remittances. The suspension of visa services at the US Embassy in Havana in 2017 sparked the largest wave of irregular migration since 1980, a desperate exodus of Cubans seeking any way out.

The economic devastation since then has been profound. Cuba’s GDP shrank by a staggering 15% in 2019 and an additional 11% in 2020. Imagine a country unable to purchase basic necessities due to banking restrictions, its public services and industries crippled. When COVID-19 hit in 2020, Cuba’s robust public healthcare system, a point of national pride, found itself under immense pressure. Its only oxygen plant, critical for treating patients, became non-operational because it couldn’t import spare parts due to the blockade. Thousands of Cubans struggled to breathe, yet Washington refused to make exceptions.

Cuba’s response to deepening crisis

Trump’s final act in office, listing Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism in January 2021, was a devastating blow. This designation makes it nearly impossible for Cuba to engage in normal financial transactions, cutting off vital trade. Then in the first 14 months of the Biden administration, the Cuban economy lost an estimated USD 6.35 billion due to the continued Trump sanctions, preventing crucial investments in its aging energy grid and the purchase of food and medicine. The Cuban peso plummeted, devaluing already low public sector wages. While the rationing system provides a subsistence diet, this level of deprivation hasn’t been felt since the “Special Period” of the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Faced with these severe constraints, the Cuban government has had to adapt. In 2020, it began to rely more heavily on the private sector as both a new source of employment and an importer of basic goods – a pragmatic step born of necessity. Over 8,000 small and medium-sized businesses have registered since 2021, and in 2023, the private sector was on track to import USD 1 billion in goods. While this rise of the private sector has boosted the import of some supplies, it has also introduced new challenges for Cuba’s socialist project by creating income disparities, a stark contrast to Cuba’s historic emphasis on equitable wealth distribution.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel has consistently emphasized the government’s commitment to providing essential services while acknowledging the need for change due to the current scenario of an ever-tightened blockade. He defines Cuba’s socialist project of social justice not merely as welfare, but as a fair distribution of income where those who earn more contribute more, and those who cannot are supported. This is the tightrope the Revolution walks: balancing economic realities with its foundational principles. The leadership insists on safeguarding the socialist project and guaranteeing essential services while resisting calls for major privatization efforts.

The pandemic, which decimated tourism, Cuba’s leading industry, further exacerbated the crisis. Despite dwindling access to hard foreign currency, the government spent hundreds of millions of dollars on medical supplies and continued to guarantee salaries, food, electricity, and water, adding USD 2.4 billion to its debt to cover basic needs.

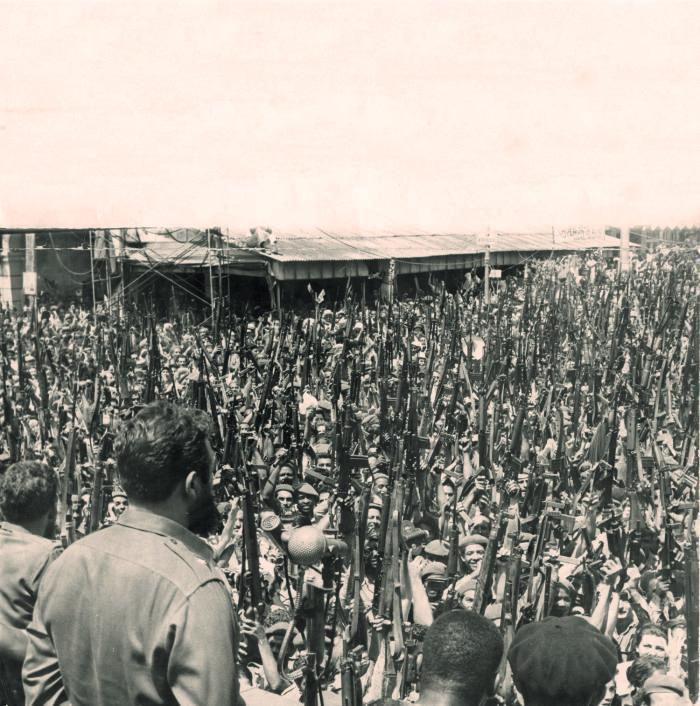

Six decades of US regime change attempts

The ultimate contradiction consuming Cuba’s every effort to meet the basic needs of its people is the open and unrelenting antagonism of the United States. The US government’s objective from day one of the Cuban Revolution has been regime change, achieved by manufacturing worsening conditions and sponsoring internal subversion. While the blockade has always hindered Cuba’s development, for the first three decades, Soviet support and a favorable environment in the Third World offset much of its impact. The 1990s, which became known as the “Special Period”, was a crisis of immense proportions, as Cuba had to face the might of the US blockade on its own, yet it forced innovative responses that allowed Cuba to survive.

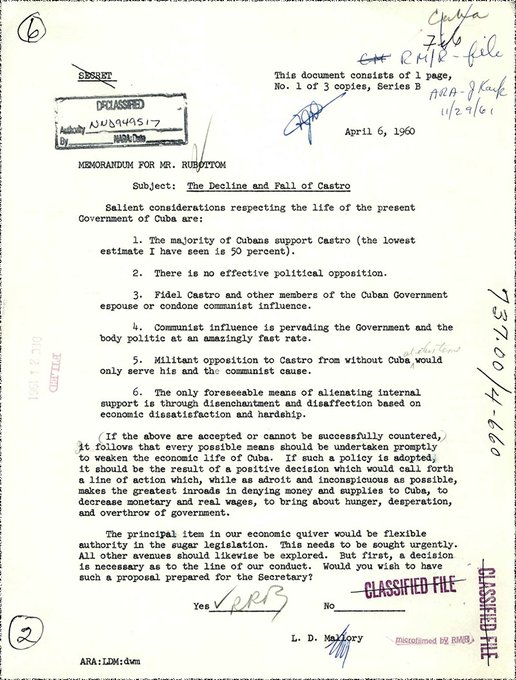

However, the current moment is different. The cumulative effect of Trump’s sanctions, the pandemic, the global economic downturn, Biden’s inaction, and the return of Trump with a vindictive Marco Rubio as Secretary of State, have created a perfect storm for the US to attempt its long-held objectives of regime change. Lester Mallory’s infamous memorandum from 1960, which explicitly stated that the blockade’s aim was to cause internal rebellion through hunger and desperation, has found a new, more sophisticated application. This strategy is forcing the Cuban state to adopt measures that might be contrary to its project but are critical for its survival in a period of great hostility.

State-owned enterprises, the bedrock of Cuba’s socialist economy, are crumbling under the inability to fund much-needed maintenance or generate enough foreign currency reserves, due to the blockade.

ETECSA, heavily sanctioned by the US, has been left with little to no options to renovate its entire internal infrastructure besides raising its rates for the first time in years. From its servers to radio base stations, all require imported technology. The state, historically capable of subsidizing everything from education and health to transportation and food, is being forced to reduce, adapt, and in some cases, relinquish its ability to meet all needs at once. Garbage collection, water services, and most critically, electricity, face such severe challenges that their dysfunction breeds not only frustration but a growing disbelief in the state’s capacity to solve these problems.

While the US government, in 60 years of economic warfare, has failed to overthrow the Cuban state outright, its measures have now begun to have their most severe impact, to the point where the Trump administration and its henchmen, like Marco Rubio, are further tightening the noose on the Cuban state’s ability to meet the people’s needs. Whatever measures Cuba takes at this moment are not signs of weakness or surrender, but a direct consequence of the crisis forced upon it by the blockade.

The people’s responses to this crisis have been varied. Since July 2021, protests, often small and isolated, have become a normal occurrence across the island, and Cubans overall have become more vocal in their criticisms and demands of the Cuban state. In response to the ETECSA price increase, Cubans across diverse sectors of society have voiced criticism. Among them are students and chapters of the Federation of University Students (FEU) across campuses which, since the announcement, have not only criticized but also led direct negotiations with the Cuban state and ETECSA to find solutions. Nonetheless, like clockwork, anti-Cuban voices in the US have tried to exploit this moment of crisis to manipulate the students’ criticisms into attempts to overthrow the Cuban Revolution.

In response to this, Roberto Morales, a high-ranking leader of the Communist Party, condemned the “media manipulations and opportunistic distortions” that “enemies of the Revolution have attempted to impose.” While legitimate critiques by the people are understandable and an important aspect of life in Cuba, he argues that they must be viewed within the larger context of a nation under siege. The objective of Trump and Rubio, as it always has been for the anti-Cuban elements in Miami, Morales declares, has been “to sow chaos, promote violence, and shatter the peace of our homeland.”

Human toll of the blockade

An even bigger response to this crisis, however, has been the largest wave of migration in Cuban history, surpassing the Mariel boatlift and the 1994 rafter crisis combined. Nearly 425,000 Cubans migrated to the US in 2022 and 2023, representing over 4% of the population. Thousands more have gone to Spain, Mexico, Brazil, and other countries. Cuba’s population has fallen below 10 million for the first time since the early 1980s, losing 13% of its inhabitants since its peak in 2012. Yet the US, which for decades has created the conditions for and promoted this mass migration of Cubans, has taken a sharp turn. Cuban asylum seekers are being deported and Cuba was just added to Trump’s travel ban list, outright banning Cubans from traveling safely and legally to the US.

This is the stark reality for Cuba: a country besieged, its people enduring great hardship, and its government adapting in ways that are both necessary and challenging for survival. The challenges are immense, and the sacrifices of its people are profound to sustain the gains of its revolution.

It is in this context that the solidarity of people in the world and in the US must be forged anew. We cannot simply be aware; we must be active. We must go beyond raising awareness and take actionable steps to support the Cuban people. This means demanding an end to the brutal and genocidal US blockade, a cruel and inhumane policy that punishes an entire nation for its commitment to self-determination. It means supporting humanitarian aid efforts, advocating for diplomatic engagement, and mobilizing for a world without sanctions and blockades. The Cuban people need more than our sympathy; they need our active, unwavering solidarity.

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2025/06/05/ ... e-on-cuba/

******

Cuba Adjusts Internet Tariff Following Popular Demands: Education and Health Prioritized

June 5, 2025

Cuba's Mesa Redonda program with ETECSA's executives and students where new adjustments to mobile data plans was announced. Photo: X/@ETECSA_Cuba.

Cuba’s state-run telecommunications company ETECSA has announced adjustments to its recent commercial measures in response to widespread criticism from various social sectors, particularly within the university sphere. The new changes include specific benefits for students and healthcare workers amid a broader economic crisis exacerbated by the U.S. blockade and technological constraints.

Amid growing public dissatisfaction over increased mobile internet prices, the Cuban Telecommunications Company S.A. (ETECSA) introduced new flexibilities aimed at mitigating the impact of recent rate hikes, especially in vulnerable sectors such as education and public health.

ETECSA, Cuba’s sole telecommunications provider, was established after the Cuban Revolution as a state-owned entity with a mandate to ensure universal, equitable, and sovereign access to communication services. Its mission has long been tied to the country’s scientific, educational, and cultural development, assigning it a social responsibility that extends well beyond commercial interests.

The announcement came from ETECSA’s Executive President, Tania Velázquez Rodríguez, during a second broadcast of the national television program Mesa Redonda. The update followed a series of exchanges with student leaders, academics, and civil society actors who raised serious concerns about affordable access to digital connectivity.

One of the most significant updates is the launch of a second 6 GB plan priced at 360 Cuban pesos (CUP), available exclusively for university students. This will bring the total monthly quota to 12 GB for 720 CUP, offering partial relief compared to the basic data plan introduced on May 30, which costs 3,360 CUP.

Additionally, ETECSA announced free mobile access to a list of roughly 40 educational and scientific websites, benefiting students, researchers, educators, and healthcare professionals. This initiative aims to protect academic development and the right to information amid economic hardship.

In coordination with state agencies, efforts will also be made to promote the use of national platforms such as Todus and Nauta email, whose data consumption is deducted from lower-cost “national megabytes.” National scientific journals will also be hosted on ETECSA servers to facilitate more affordable access to key academic resources.

Velázquez also stated that Cuba’s educational infrastructure—particularly in universities, vocational high schools (IPVCE), pedagogical institutes, and provincial technical schools—will be strengthened. This includes improvements in Wi-Fi zones and the installation of local servers with backup energy sources.

Minors will be granted academic internet access upon authorization from their legal guardians, as part of a broader effort to ensure digital equity among young students. On the audiovisual front, the content platform PICTA, developed by the University of Computer Sciences (UCI), will incorporate highly demanded educational materials, helping integrate visual content into learning processes.

During the broadcast, Interim Communications Minister Ernesto Rodríguez Hernández emphasized that the high cost of telecommunications in Cuba is not solely the result of internal policies, but also a consequence of the U.S. economic blockade, which drives up technology costs and restricts international providers.

“Many providers have withdrawn or limited their services, including critical technical support,” Rodríguez explained. He described the updated measures as “a difficult but necessary decision to set the country on the path to recovery. It was better to act now than to wait for a worse outcome.”

From the University Student Federation (FEU), its national president Ricardo Rodríguez González stressed that student concerns mainly revolve around the high cost of data plans in relation to academic demands, particularly in science and technology fields that require frequent data usage. He underscored that statements from university faculties were issued with respect and aimed at seeking optimal solutions for both the nation and its academic community.

Regarding the choice of the 6 GB package as the baseline offer, Velázquez explained that this was based on internal ETECSA studies of average mobile data consumption among prepaid users. The goal, she said, was to establish a “representative and fair” plan that would not restrict access to essential educational or informational platforms.

The validity period for these plans will extend to 35 days, allowing unused data to roll over if a new top-up is made within that timeframe.

https://orinocotribune.com/cuba-adjusts ... ioritized/

******

U.S. Diplomacy in Cuba: Subsidies and interference

“Why will there never be a coup d'état in the United States? Because there is no U.S. embassy in Washington”, says an old popular joke.

Author: Raúl Antonio Capote |

informacion@granmai.cu

Author: Delfin Xiqués |

xiques@granma.cu

june 4, 2025 10:06:31

U.S. Department of State: Background Notes on Cuba. Photo: Ecured

“Why will there never be a coup d'état in the United States? Because there is no U.S. embassy in Washington”, says an old popular joke.

U.S. embassies, with a long tradition in coups d'état and political subversion -Paraguay 1954, Guatemala 1954, Dominican Republic 1963, Brazil 1964, Argentina 1976, Bolivia 1971, Uruguay 1973, Chile 1973-, became the base of operations for destabilization in the continent.

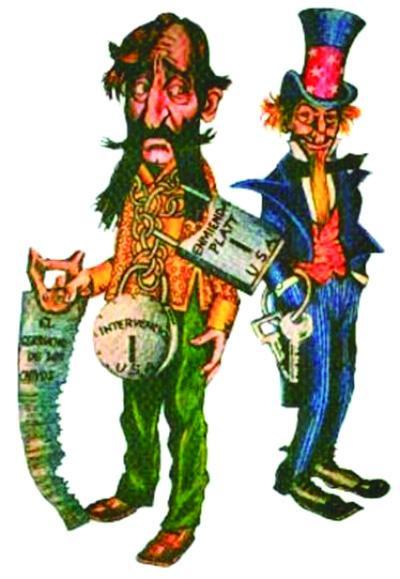

The military occupation, the imposition of the Platt Amendment in Cuba and the multiple armed interventions of the United States in the internal affairs of the Island, during the first decades of the 20th century, symbolized the advent of the neocolonial Republic.

Then we had Yankee embassy in which more than ambassadors, proconsuls invested with more authority than a Spanish Captain General, bossed presidents, parliamentarians and military.

That lasted until January 1959, when the Revolution triumphed. There were no direct bilateral diplomatic ties between the two countries between 1961 and 2015, after President Dwight D. Eisenhower broke off relations with the largest of the Antilles.

U.S. Ambassadors to Cuba

Herbert G. Squiers: May 20, 1902 - December 2, 1905

- He was a fervent annexationist. He participated on behalf of his country in the signing of the first treaty on the Isle of Pines; he was such an interferenceist that he forced the U.S. State Department in 1905 to remove him from his post.

William E. Gonzales: June 21, 1913-December 18, 1919

- On August 9 he ratified the approval of the government of General Mario García Menocal, who by then succeeded that of General José Miguel Gómez, making use of the Platt Amendment.

Boaz W. Long: June 30, 1919 - June 17, 1921

- During his mission in Cuba, Enoch H. Crowder is appointed with the rank of “personal envoy” of U.S. President Warren G. Harding. The “envoy” supervised Cuban state activities and acted as the highest authority, even above the President of the Republic.

Enoch H. Crowder: February 10, 1923 - May 28, 1927

- On March 5, 1923, he presented his credentials as the first ambassador of his country in the Caribbean nation, when the Northern Legation on the Island became an Embassy.

Harry F. Guggenheim: October 10, 1929 - April 2, 1933

- He was ambassador during the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, which he supported on behalf of his government.

Sumner Welles: April 24, 1933 - December 13, 1933

- Sent to Cuba as “mediator” between the dictator Gerardo Machado and the popular forces. His presence was declared unwelcome by the Hundred Days Government, due to his interfering attitude.

Jefferson Caffery: February 23, 1934- March 9, 1937

- He continued the same line of his predecessor and began to conspire with elements opposed to the revolutionary government to overthrow it.

Robert Butler: May 22, 1948- February 10, 1951

- On March 11, 1949, U.S. Marines, who had arrived in Havana's port, outraged the statue of José Martí. The ambassador's apology showed the Government's contempt for him; he did not even know the name of Cuba's National Hero.

Arthur Gardner: May 28, 1953 - June 16, 1957

- He was a staunch supporter of Fulgencio Batista. The CIA station in Havana had at that time more than two dozen operational officers in its embassy. During his work, the Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities (BRAC) was created on the island.

Earl E. Smith: June 3, 1957 - January 19, 1959

- Openly supported the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Smith resigned on January 10, 1959 and was replaced by Phillip W. Bonsal.

Heads of the U.S. Interests Section (USINT)

The U.S. Interests Section (USINT) operated from September 1, 1977 to July 20, 2015, and became the headquarters of the counterrevolution in Cuba.

Lyle Franklin Lane: 1977-1979

- He was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the first Chief of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana.

Curtis W. Kamman: 1985-1987

- On January 29, 1987, Commander-in-Chief Fidel Castro Ruz warned Curtis W. Kamman about the espionage activities carried out from USINT. In the summer of that year more than one hundred CIA officers, among those stationed at SINA, were unmasked.

Joseph Sullivan: 1993-1996

- Maintained close ties with “opposition” groups, among them the “dissidents” of Concilio Cubano.

Vicki Huddleston: 1999-2002

- In 2000, USINT sought to manipulate an event of great international prestige such as the 7th edition of the Havana Biennial. Parallel to the event's activities, officials of the Interests Section developed their own plan: an aggressive operation of influence and recruitment.

James Cason: 2002-2005

- Following instructions from the White House, he used diplomatic immunity to organize meetings in his official residence with leaders of counterrevolutionary organizations. He supported “opposition” organizations with all kinds of resources, which was denounced in 2003 by Cuban television.

Michael E. Parmly: 2005-2008

- He gave continuity to the work of his predecessor. Notes exchanged between Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello and Cuban-Americans living in Florida implicated Parmly with Cuban-born terrorist Santiago Álvarez Fernández-Magriñá.

Jonathan D. Farrar: 2008-2010

- In 2010 the Wikileaks site declassified a cable from Farrar in which he acknowledged that he was in contact “with most of the official dissident movement in Havana,” whose members, he claimed, frequently visit USINT.

John Caulfield: 2011 - 2014

- On June 19, 2012, USINT culminated an Introduction to Journalism course through which about 26 counterrevolutionaries obtained their diplomas, issued by Florida International University.

All of the following served as Chargé d'Affaires a.i. at the U.S. Embassy.

Mara Tekach: July 20, 2018-July 21, 2020.

- On November 20, 2019, Tekach was charged with working closely with Cuban counterrevolutionary José Daniel Ferrer. He focused his work on the purpose of recruiting mercenaries, identified areas of the economy against which to target coercive measures, and actively engaged in defamation and open incitement to violence.

Timothy Zúñiga-Brown: July 31, 2020 to July 14, 2022

- He worked to create an artificial crisis, trying to portray as political an economic emigration caused, in the first place, by the very blockade measures designed for that purpose. He was determined, like his predecessors, to provoke an explosion on the island by any means necessary.

Mike Hammer November 14, 2024

- The “Ambassador of the Cuban counterrevolution” carries out an active provocative work with the aim of creating a diplomatic crisis that will lead to his expulsion from Cuba and justify the closing of the embassy. To that end he consciously violates everything established.

https://en.granma.cu/mundo/2025-06-04/u ... terference