Dialogue with Fudan University’s China Institute: Is China really socialist?

Dialogue with Fudan University’s China Institute: Is China really socialist?

The second Friends of Socialist China delegation to China took place from 26 May to 5 June 2025. The delegation, composed of 15 comrades from Britain and the US, visited Xi’an and Yan’an (Shaanxi), Dunhuang and Jiayuguan (Gansu) and Shanghai, visiting important historical sites, learning about China’s development, attending the 4th Dialogue on Exchanges and Mutual Learning among Civilisations, and engaging meeting with a range of organisations.

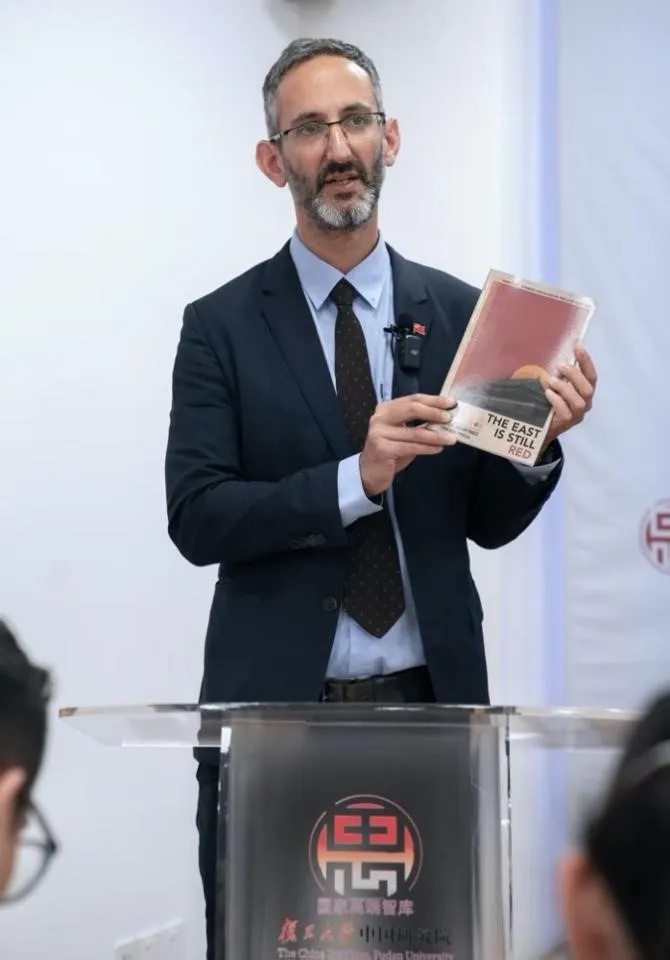

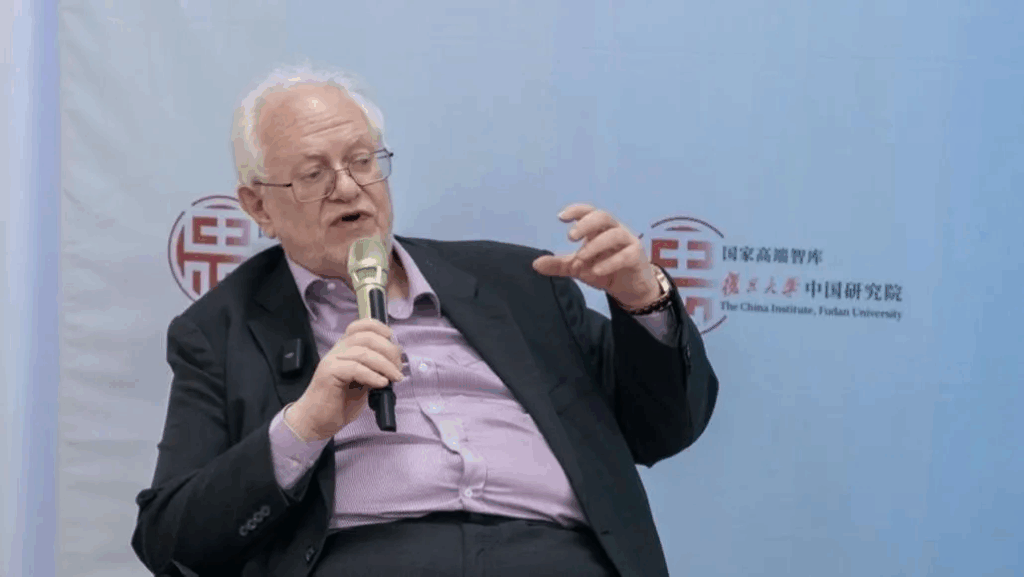

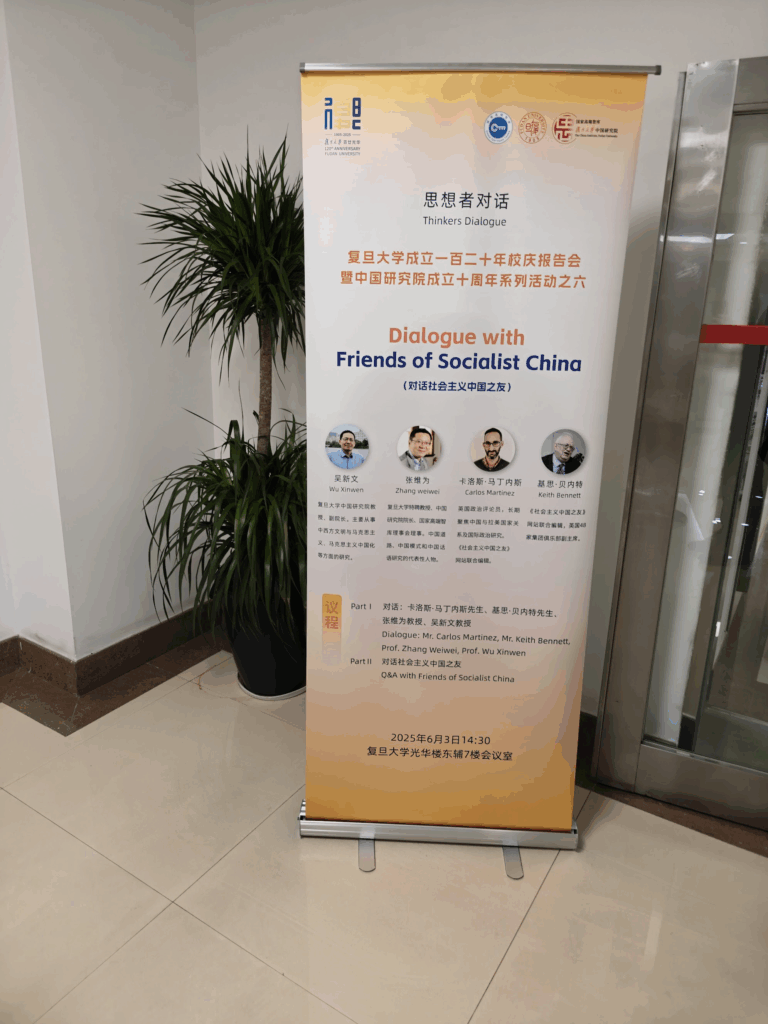

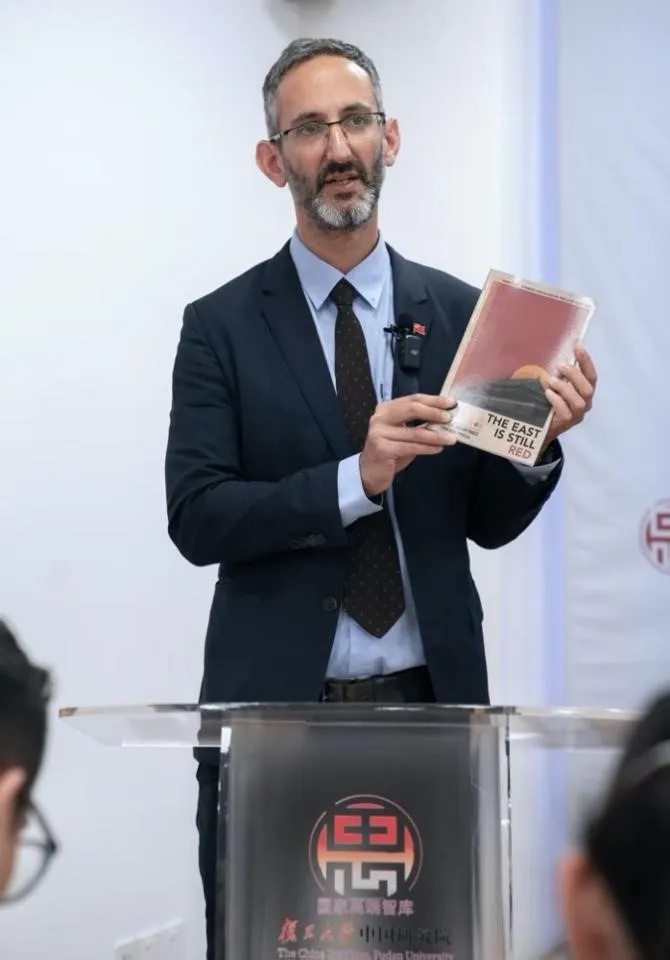

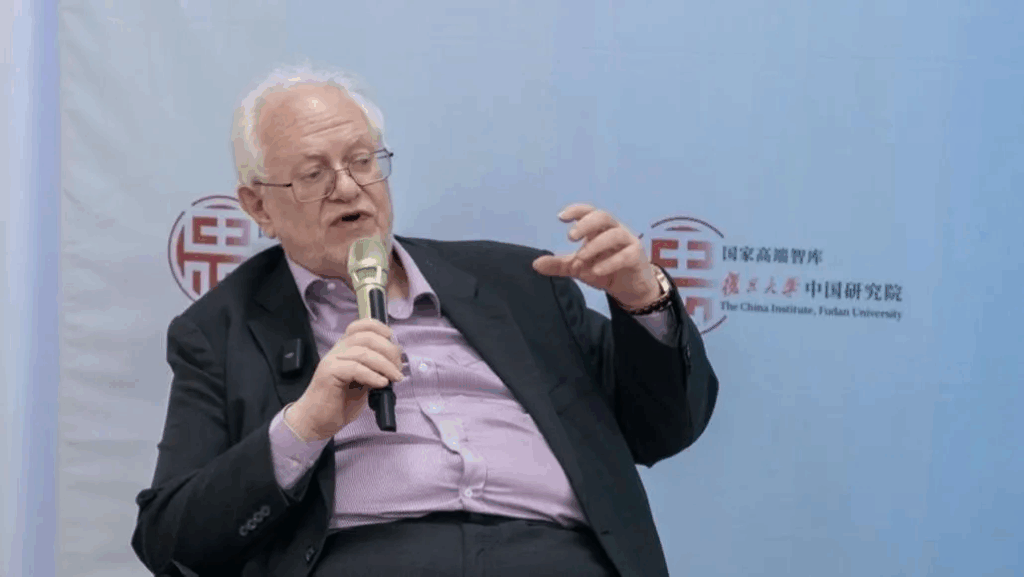

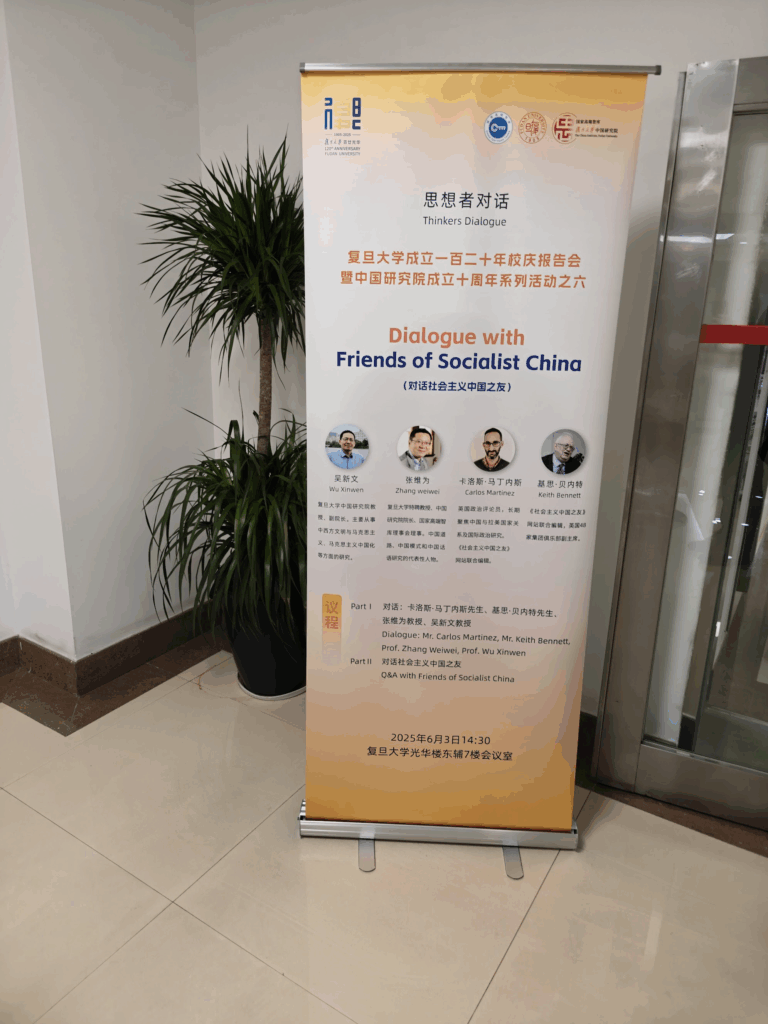

On Monday 3 June, the delegation participated in a dialogue with the China Institute of Shanghai’s Fudan University, consisting of a panel discussion featuring Professor Zhang Weiwei, Professor Wu Xinwen, and Friends of Socialist China co-editors Carlos Martinez and Keith Bennett, followed by a wide-ranging discussion with the audience.

We reproduce below a report of the event from the China Institute WeChat channel, which has been machine-translated. The full video can be found on the China Academy website, and is embedded below. We will also be publishing a delegation report in due course.

(Video at link.)

On the afternoon of June 3, Carlos Martinez, co-editor of the Friends of Socialist China website, and Keith Bennett, vice chairman of the British 48 Group Club, led a delegation of Friends of Socialist China to visit the China Institute of Fudan University. Professor Zhang Weiwei, director of the National High-end Think Tank Council and dean of the China Institute of Fudan University, and Professor Wu Xinwen, vice dean, had in-depth dialogues and interactive exchanges with Mr. Martinez, Mr. Bennett and other members of the delegation on Chinese socialism and its global significance.

In his speech, Professor Zhang Weiwei welcomed the Friends of Socialist China delegation and briefly introduced China’s exploration of socialism along the way and its impact on the outside world.

Mr. Martinez’s speech revolved around the core ideas of his book “The East is Still Red: Chinese Socialism in the 21st Century”, pointing out that the Western world has a lot of fear and negative reports about China, but very few achievements and positive reports about China. He believes that China’s achievements in poverty alleviation have attracted worldwide attention. In the past 40 years, 800 million people have escaped poverty. China’s poverty alleviation standards in housing, food, clothing, drinking water, electricity, education, and medical care are basically equivalent to the living standards of the middle class in the global South . He highly praised China’s achievements in environmental protection and pointed out that China has become the world’s only renewable energy superpower, with wind and solar power generation accounting for 60% of the world , electric bus production accounting for 98% of the world , and electric vehicle production and sales accounting for more than 70% of the world . He criticized the West for attributing China’s achievements since reform and opening up to a certain form of capitalism, pointing out that if China adopted capitalism, it would not be possible to give priority to improving the living standards of the vast majority of people, especially the vulnerable groups, and it would not be possible to give priority to the development of renewable energy; in capitalist society, wealth is directly tied to public power, which is not the case in China. He believes that China is still red, as it was in the past and still is now.

Professor Zhang Weiwei affirmed Mr. Martinez’s view that “the East is still red” and discussed the three characteristics of Chinese socialism: first, the dominant position of public ownership is guaranteed, including the state’s ownership of land and strategic resources; second, the political, social and capital forces have formed a balance that is beneficial to the vast majority of the people, making most Chinese people the beneficiaries of globalization; third, the Communist Party of China is a party of overall interests, which is completely different from the partial interest parties in the West. As a civilized country that is “the sum of hundreds of countries”, China has formed a tradition of a unified ruling group in its long history. The Communist Party of China is, to some extent, the continuation and development of this tradition.

Mr. Bennett agreed with Professor Zhang Weiwei’s views. He believed that the key to defining whether China is socialist or not lies in whether the state has a dominant position in the economy, which means that we should not only pay attention to state-owned enterprises or land ownership, but also pay attention to enterprises of a cooperative nature. He went on to point out that whether it is an organization at the township level or a large enterprise like Huawei, they are essentially cooperatives, which is very different from private capitalist ownership. He also believed that with the strengthening of the leadership role of the Communist Party of China, some large private enterprises also need to serve the overall interests of the country, society and the majority of the people. He emphasized that China under the leadership of the Communist Party of China is the only country in the world that has proposed solutions to the real survival problems of mankind, and many of its propositions have been accepted by the vast majority of countries in the world.

Professor Wu Xinwen pointed out in the dialogue that Chinese socialism has both particularity and universality, and that it is necessary to expand its universal significance and answer questions such as “what can China contribute to the world”. He said that when the official expression “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is used, it represents a defensive position, which means that China’s socialism is not Soviet-style or Eastern European-style socialism, but socialism with Chinese characteristics. He emphasized that the reason why China is socialist rather than state capitalism is that the main policy makers in China are the Communist Party of China, not capital interest groups.

The two sides also discussed issues such as the construction of the global China narrative, the West’s “new Cold War” against China, and the Latin American socialist movement.

During the question-and-answer session, Professor Zhang Weiwei and other members of the delegation had a lively interaction on issues such as the China – Africa cooperation model, differences in the financial systems of China and the United States, full-process people’s democracy, China-Latin America strategic cooperation, the adaptive dilemma of Western-style democracy in China, the prospects for the development of China-Africa relations, the strategic direction of China’s diplomacy, and the relationship between domestic development and international responsibilities.

After the event, the two sides presented books to each other and took photos together.

https://socialistchina.org/2025/06/06/d ... socialist/

https://socialistchina.org/2025/06/06/d ... socialist/

What’s wrong with Western claims of China’s “debt burden” on poor nations

What’s wrong with Western claims of China’s “debt burden” on poor nations

The explainer article below, originally published on Xinhua News Agency, challenges Western allegations that China is imposing a “debt trap” on developing countries through loans tied to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The article specifically addresses the recent analysis from Australian foreign policy thinktank the Lowy Institute claiming that the poorest 75 countries in the world are due to pay record high debt repayments to China this year.

The authors write: “A closer look at the debt structure and facts will prove that those allegations cannot hold water.” They note that the lion’s share of developing world debt is in fact owed to Western lending institutions. World Bank data indicates that, for Sub-Saharan Africa, bilateral debt with China accounts for 11 percent of the total. Furthermore, debt to Chinese entities typically incurs far lower interest rates, and is associated with longer maturities and greater repayment flexibility. Unlike loans from Western multilateral lending institutions, China’s loans come without punishing conditions of “reform” – that is, privatisation and liberalisation measures.

“In the 46 countries that participated in the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative, Chinese creditors accounted for 30 percent of all claims and contributed 63 percent of debt service suspensions… China’s debt reduction has already doubled the average reduction scale of the G7 countries.”

The article also highlights that China’s loans are typically focused on infrastructure, telecommunications and green energy, and are thus helping the poorest countries to generate wealth, improve living standards, and break out of underdevelopment.

The article concludes that the “debt trap” narrative is simply a rhetorical strategy by Western powers to undermine China’s growing mutually-beneficial relationships with the countries of the Global South.

A recent report published by an Australian think tank claimed that many developing countries were on the hook for record high debt repayments to China in 2025, as bills come due from the lending under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Once again, China became an easy target to blame. In recent years, Western think tanks and media outlets have kept hyping up the so-called Chinese “debt trap.” However, a closer look at the debt structure and facts will prove that those allegations cannot hold water.

Who is the biggest lender?

The think tank report blamed China as the major source of debt pressure for developing countries, warning that “now, and for the rest of this decade, China will be more debt collector than banker to the developing world.”

In fact, for many developing countries, a majority of debts are owed to Western donors and multilateral institutions, while Chinese entities’ loans account for only a minority.

For example, in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, 66 percent of public and publicly guaranteed debt is held by private bondholders and multilateral creditors, while bilateral debt with China accounts for 11 percent, as the International Debt Report 2023 released by the World Bank (WB) Group has shown.

As for Sri Lanka, its debt to Chinese entities accounts for only 10.8 percent of its total external debt, while private creditors taking the lion’s share of 53.6 percent, multilateral creditors — 20.6 percent, according to data released by the country’s Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance, Economic Stabilization & National Policy as of March 2023.

Spokesperson for Pakistan’s Foreign Ministry Mumtaz Baloch has previously slammed a New York Times article’s accusations that “Chinese loans led to Pakistan’s economic crisis,” retorting that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has made positive and transparent contributions to Pakistan’s national development.

The total public debt involved in the CPEC project is only a small part of Pakistan’s total debt, Baloch said, noting that the public trade debt from China has low interest rates and long maturities.

Contrary to portrayals by Western think tanks and media of China as an unforgiving lender, China has actively contributed to global debt relief efforts over the years.

In the 46 countries that participated in the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative, Chinese creditors accounted for 30 percent of all claims and contributed 63 percent of debt service suspensions.

Since 2016, China, as a bilateral creditor, has been responsible for roughly 16 percent of global debt relief, surpassing the United States and the WB, said professor Ding Yibing, dean of School of Economics, Jilin University, adding that China’s debt reduction has already doubled the average reduction scale of the G7 countries.

Amid the growing concerns of a debt default, China has always adhered to the principle of equality in bilateral relations and proactively participates in just and fair negotiations with different nations, said Song Wei, a professor at the School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Beijing Foreign Studies University.

China’s contribution to debt relief exemplifies the international obligations expected for a responsible major country, Song said.

What are China’s loans really for?

The report claimed that the pressure to repay China’s debt was raising the debt vulnerability of developing countries and putting strain on local funding for health and education as well as climate change mitigation.

However, the vast majority of developing countries and BRI partner countries see the truth behind the false narrative very clearly.

China’s financial engagement has helped Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) countries and other developing countries meet critical infrastructure needs and build self-sufficiency, said Pedro Barros, a researcher at Brazil’s Institute for Applied Economic Research.

“Chinese financing has been vital for regional growth. Ecuador, for example, once reliant on electricity imports, now has multiple hydropower plants built with China’s help, significantly reducing power shortages,” he said.

A report by the Latin America and the Caribbean Network on China revealed that China-aided infrastructure projects in the region have generated over 777,000 jobs between 2005 and 2023.

In addition, contrary to what the report said that China could use the repayments for geopolitical leverage, China’s loans always focus on shared development goals without imposing political conditions, experts say.

As Africa’s largest partner in the green energy transition, China provides African consumers with “affordable, durable and accessible” green products, without imposing conditions, said Adhere Cavince, a Kenya-based international relations scholar.

In contrast, Western aid is often tied to political and economic conditions such as austerity measures, privatization and “democracy promotion,” which often cause civil strife, Cavince added.

The so-called “debt trap” was further challenged by a report from Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, which described China’s loans as “patient capital” — long-term financial options that boost connectivity, enhance trade and attract investment.

Why the West passes the buck

For years, the West has been hyping up the so-called “debt trap” resulting from Chinese loans, in what many experts described as an attempt to disrupt normal cooperation between China and the developing world.

The “debt trap” narrative promoted by Western powers against China is “highly hypocritical,” Honduran Vice Foreign Minister Gerardo Torres told Xinhua in 2024 on the sidelines of the inaugural LAC Development Forum in Beijing.

Noting that China-LAC win-win cooperation aligns closely with the region’s development needs, Torres said Western countries lack the moral stand to criticize the so-called Chinese “debt trap,” given their historical role as major creditors to the region.

“For decades, Western nations have imposed their financial criteria through loans that never led to true development,” he said, referring to the mega-dollar debts owed by LAC countries to Western lenders.

Barros also labeled the Western promotion of the “debt trap” narrative as a rhetorical device.

“For decades, Western countries have misused financial tools, undermining democracy and development in LAC. Now, they accuse China of doing the same,” he said. “But the abuses in the past weren’t about the loans themselves — they stemmed from a colonial mindset that persisted for centuries.”

China’s growing engagement with the developing world unsettles some nations in the West, said Humphrey Moshi, director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. “The ‘debt trap’ narrative aims to discredit China’s growing influence in Africa and maintain Western dominance,” he said.

“They use narratives like ‘neocolonialism’ and ‘debt trap’ as geopolitical tools to smear China and weaken the effectiveness of its development partnerships with developing countries,” Cavince said.

“It is neither in the interest of emerging economies nor that of China,” Cavince added. “That is why, despite the hype, no African country is taking it seriously.”

https://socialistchina.org/2025/05/31/f ... -on-china/

From containment to confrontation, from cold to hot: the US drive to war on China

From containment to confrontation, from cold to hot: the US drive to war on China

In the following article, Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez argues that the US-led New Cold War against China is failing. Despite extensive efforts to contain China’s rise – through tariffs, sanctions, and attempts at economic decoupling – China continues to grow economically and technologically. It now leads globally in multiple areas including renewable energy, electric vehicles, and advanced manufacturing. Its global reach is expanding, as evidenced by its central role in BRICS, the Belt and Road Initiative, and its status as the top trading partner for three-quarters of the world’s countries.

The West’s tariffs and sanctions have clearly backfired, invigorating China’s domestic industries rather than weakening them.

However, Carlos warns that the failure of “cold” methods could well provoke a shift toward direct military confrontation. The article identifies Taiwan as the most likely flashpoint, with the US escalating arms sales to the island and increasing its military deployments in the region. In the last two decades, successive US administrations, Democratic and Republican alike, have undermined the One China policy and fanned separatist sentiment, in defiance of international law.

Military preparations, including AUKUS, the rearmament of Japan, and new US bases in the Philippines, reflect a growing bipartisan consensus in Washington in favour of war planning.

This all adds up to accelerating preparations for war with China – a war with the objective of dismantling Chinese socialism, establishing a comprador regime (or set of regimes), privatising China’s economy, rolling back the extraordinary advances of the Chinese working class and peasantry, and replacing common prosperity with common destitution. Needless to say, this would be disastrous not just for the Chinese people but for the entire global working class.

Carlos calls for resolute opposition to this dangerous escalation.

The New Cold War is not working

The US-led ‘cold’ war against China is manifestly failing in its objectives of suppressing China’s rise and weakening its global influence.

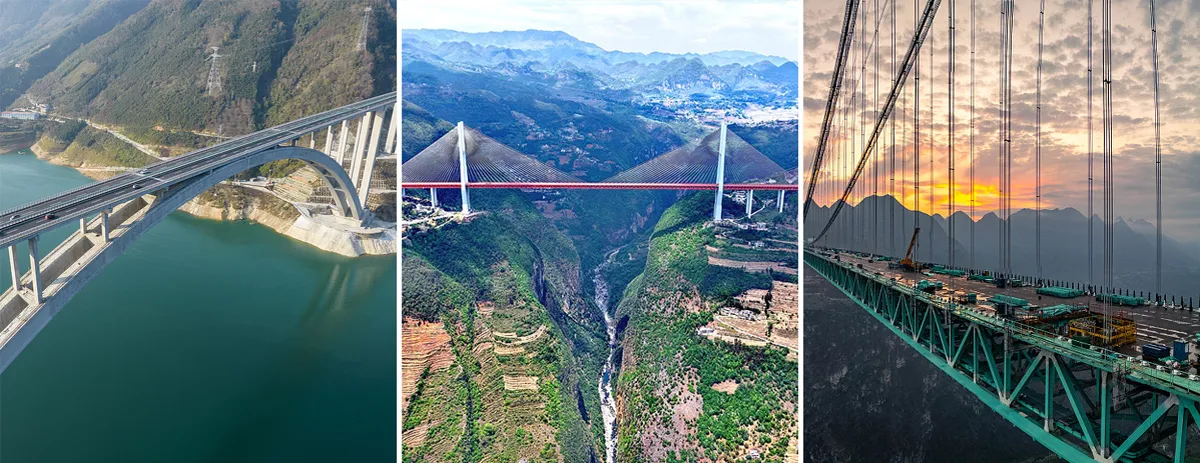

China’s economy continues to grow steadily. In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, it is by now the largest in the world. Its mobilisation of extraordinary resources to break out of underdevelopment and become a science and technology superpower appears to be paying substantial dividends, with the country establishing a clear lead globally in renewable energy, electric vehicles, telecommunications, advanced manufacturing, infrastructure construction and more. It is by far the global leader in poverty alleviation and sustainable development. Sanctions on semiconductor exports have not slowed down China’s progress in computing, and indeed have had an enzymatic effect on its domestic chip industry. The spectacular success of DeepSeek’s open-source R1 large language model indicates that the US can no longer take its leadership in the digital realm for granted.

Meanwhile, the West’s attempts to ‘decouple’ from China have yielded precious little fruit. While a handful of imperialist countries have promised to remove Huawei from their network infrastructure, and while sanctions on Chinese electric vehicles mean that consumers in the West have to pay obscene sums for inferior quality cars, China’s integration and mutually-beneficial cooperation with the world has continued to expand. China is the largest trading partner of approximately two-thirds of the world’s countries. Over 150 states are signed up to the Belt and Road Initiative. China lies at the core of BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Trump’s tariffs were meant to coerce China into accepting the US’s trade terms and to force other countries to unambiguously join Washington’s economic and geopolitical ‘camp’, thereby alienating China. Nothing of the sort has taken place. Even the normally supine European Union has denounced the tariffs and signalled its intention to expand trade with China.

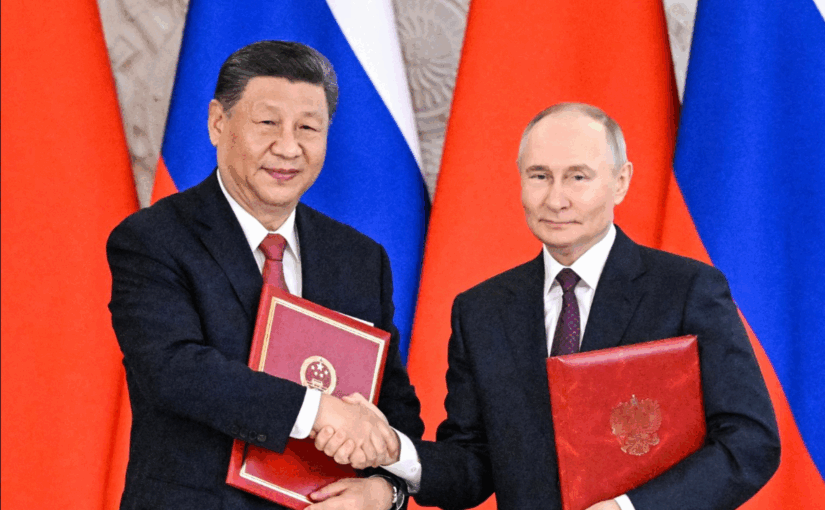

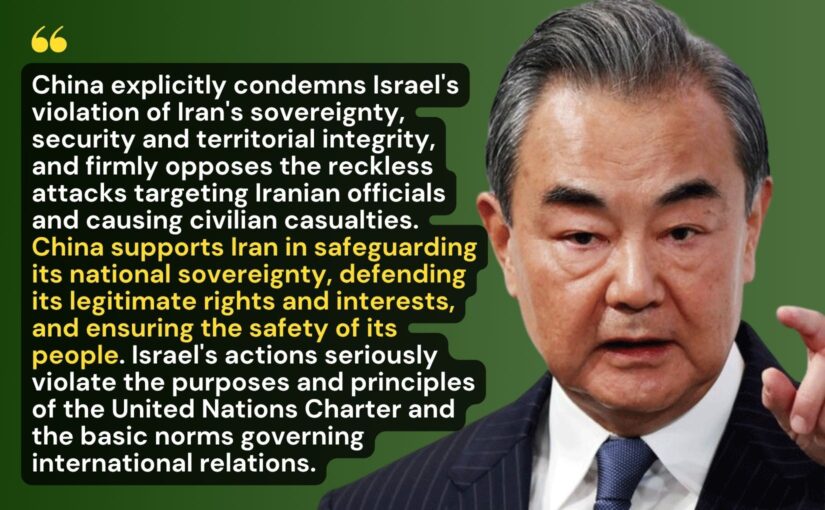

In summary, the Project for a New American Century is not going well. Zbigniew Brzezinski famously wrote in his The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives (1997) that “the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition of China, Russia, and perhaps Iran, an ‘anti-hegemonic’ coalition united not by ideology but by complementary grievances.” Precisely such an anti-hegemonic coalition exists, and is uniting the countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean and the Pacific in a project of building a multipolar future, thereby posing an existential challenge to the so-called ‘rules-based international order’ based on the principles of unilateralism, war, destabilisation, coercion and unequal exchange.

From cold war to hot war?

So far, so positive. But we mustn’t forget that “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. If imperialist policy is not having its intended effect, there is a very real risk that the US ruling class and its hangers-on will resort to outright war in pursuit of their hegemonic ambitions.

Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, said Mao Zedong. And while the US’s economic dominance may be waning, it still has an awful lot of guns with which to project political power. Donald Trump announced recently, sat next to genocidal-maniac-in-chief Benjamin Netanyahu in the White House, that the next US budget will assign a record-breaking trillion dollars to the military. This is more than three times China’s military expenditure, and approximately ten times that of Russia. Meanwhile the US has over 800 foreign military bases, a stockpile of around 5,500 nuclear warheads, and vast deployments of troops and weapons around the world, increasingly concentrated in China’s neighbourhood.

Taiwan as the trigger

The flashpoint for a military attack on China would most likely be Taiwan Province, which has long occupied pride of place in the US’s encirclement campaign.

Taiwan has been part of China since many centuries ago. It was seized by Japan in 1895 and returned to Chinese control the end of World War 2, as agreed at the Potsdam Conference. Defeated in the Chinese Civil War (1946-49), Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang forces decamped to Taiwan and declared the island to be the true ‘Republic of China’. It would have been quickly integrated into the People’s Republic but for the Truman administration positioning the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet in the Taiwan Strait in 1950, calculating that de-facto American control would bring significant strategic advantages, including the ability to maintain a permanent nuclear threat against China, the Soviet Union and the DPRK.

In the words of the criminal warmonger General Douglas MacArthur, Taiwan was to become the US’s “unsinkable aircraft carrier” in the region, and the cornerstone of its First Island Chain strategy – a collection of military bases, weapons and troops deployed specifically in order to contain and encircle the People’s Republic of China.

Undermining of the One China principle

Under the Shanghai Communiqué, issued in 1972 on the last evening of Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China, the United States “acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position”. As such the US – along with 180 other countries – supports the One China principle and recognises the People’s Republic as the sole legal government representing the whole of China. However, the US has maintained close economic and military links with Taiwan, and adopts a posture of “strategic ambiguity” in its relations with the island.

In recent years, seeking to provoke conflict and undermine China, Washington has increased its support for Taiwanese separatists and ramped up its supply of weapons to the administration in Taipei.

Bipartisan consensus on escalation

Joe Biden stated multiple times – in clear contravention of the US’s commitments and with no basis in international law – that the US would intervene militarily if China attempted to use force to change the status quo concerning Taiwan. In 2023, Biden signed off on direct US military aid to Taiwan for the first time, with a BBC article observing that “the US is quietly arming Taiwan to the teeth”. Then-Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 trip to Taipei was the highest-level US visit to the island in a quarter of a century.

In January 2023, US Air Force General Mike Minihan sent a memo to the officers under his command saying “my gut tells me” there will be a war between the US and China in 2025 and that the trigger for that war would be Taiwan. The memo calls on US armed forces to “be prepared for deployment at a moment’s notice” in order to enter a war in the Taiwan Strait and “defeat China”.

Republicans are no less bellicose on this issue. Mike Pompeo, Trump’s secretary of state from 2018 to 2021, said in 2022: “The United States government should immediately take necessary and long overdue steps to do the right and obvious thing: that is to offer the Republic of China, Taiwan, America’s diplomatic recognition as a free and sovereign country.”

Trump’s new cabinet is packed with notorious anti-China hawks such as Marco Rubio (secretary of state), Pete Hegseth (defence secretary), Mike Waltz (national security advisor) and Peter Navarro (senior counsellor for trade and manufacturing).

An internal guidance memo circulated by Hegseth in March calls on the US military to “prioritise deterring China’s seizure of Taiwan and shoring up homeland defence”. A report in the Washington Post states that the document “outlines, in broad and sometimes partisan detail, the execution of President Donald Trump’s vision to prepare for and win a potential war against Beijing”. Incidentally, the memo also provides some useful context for the Trump regime’s moves towards extrication from the Ukraine conflict: since “China is the Department’s sole pacing threat”, the “threat from Moscow” will have to be “largely attended by European allies”. In other words, the US’s strategy constitutes a reiteration and deepening of the Obama-Clinton Pivot to Asia.

These escalations over Taiwan by successive US administrations are closely linked to the creation of the AUKUS nuclear pact between the US, Britain and Australia, as well as to the US’s encouragement of Japanese rearmament and the establishment of four new US military bases in the Philippines – “a key bit of real estate which would offer a front seat to monitor the Chinese in the South China Sea and around Taiwan”, according to the BBC.

This all adds up to accelerating preparations for war with China – a war with the objective of dismantling Chinese socialism, establishing a comprador regime (or set of regimes), privatising China’s economy, rolling back the extraordinary advances of the Chinese working class and peasantry, and replacing common prosperity with common destitution. Needless to say, this would be disastrous not just for the Chinese people but for the entire global working class.

The drive to war against China must be resolutely opposed.

https://socialistchina.org/2025/05/31/f ... -on-china/

******

Special Report: China’s Strategic Commitment to Latin America and the Caribbean

June 6, 2025

Chinese President Xi Jinping poses for a group photo with guests attending the opening ceremony of the China-CELAC Forum's fourth ministerial meeting in Beijing, May 13, 2025. Photo: Xinhua/file photo.

By Misión Verdad – Jun 6, 2025

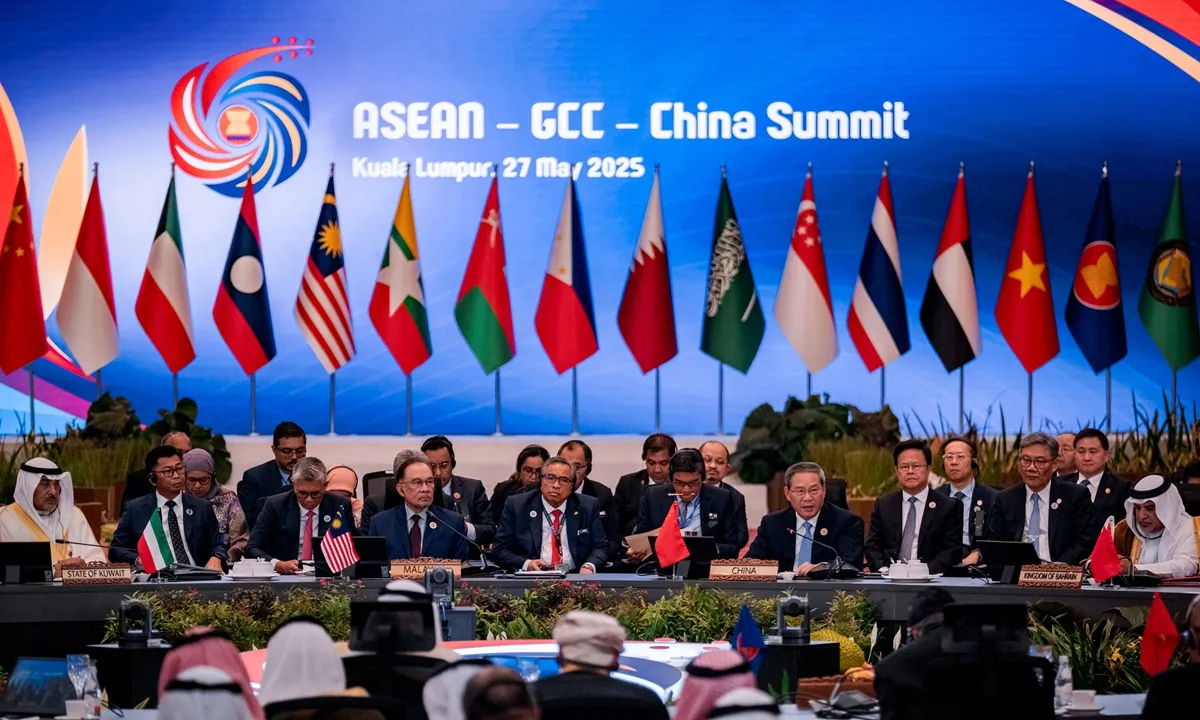

During the recent China-CELAC Forum ministerial summit, the president of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, delivered a speech clearly demonstrating China’s roadmap toward Latin America and the Caribbean: a long-term strategic agenda aimed at consolidating a community of shared destiny.

In his speech, Xi reaffirmed Beijing’s commitment to a framework for cooperation based on equality, mutual respect, and shared benefits.

From his first words, the Chinese leader struck a warm and symbolic note by recalling that, after 10 years of existence, the China-CELAC Forum has evolved from a diplomatic “sapling” to becoming “an imposing tree,” a reflection of the maturity reached in this relationship.

However, the message was not limited to rhetoric. Xi also concretely demonstrated results, political priorities and new lines of financing, investment, and infrastructure, which outline the central place that Latin America occupies in China’s international strategy.

He noted, for example, that thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative, over 200 infrastructure projects have already been implemented between China and the region, creating more than one million jobs.

He focused on concrete advances such as the port of Chancay in Peru, a strategic hub that now connects Latin America with Asia across the Pacific.

He also highlighted that bilateral trade surpassed US$500 billion for the first time last year, representing a growth of over 40 times since the beginning of the century.

Strategic cooperation agenda

President Xi then articulated an agenda summarized in five programs:

1. Solidarity program: It promises that over the next three years, 300 members of CELAC political parties will be invited annually to China to exchange experiences in governance.

2. Development program: Commits a 66 billion yuan credit line to support projects in the region and encourage Chinese investment in sectors such as infrastructure, energy, the digital economy, and artificial intelligence.

3. Civilization program: It seeks to strengthen cultural ties through a Latin American and Caribbean Art Season, joint archaeology projects, and the fight against the illicit trafficking of cultural property.

4. Peace program: It strengthens China’s support for the region as a Zone of Peace with new plans for police training, cooperation in cybersecurity, the fight against organized crime, and drug control.

5. People’s program: It seeks to foster people-to-people connections between China and Latin Americans and the Caribbean through advanced education programs, visas, tourism, and direct exchanges between the peoples.

One of the most notable announcements was the creation of a new line of credit of 66 billion yuan, equivalent to approximately $9.18 billion, intended to finance infrastructure and development projects in CELAC member countries.

The significance of this financing lies not only in its volume but also in the fact that it is denominated in yuan, which is part of China’s broader commitment to promoting regional financial cooperation outside the dollar system.

In the area of infrastructure, China reaffirmed its commitment to new investments in ports, highways, and energy projects.

Cooperation is also expanding into emerging sectors of high strategic value. Beijing has placed particular emphasis on the joint development of clean technologies, 5G telecommunications, artificial intelligence, the digital economy, and cybersecurity.

These areas not only aim to modernize Latin American economies but also to integrate them more closely into Chinese technological value chains, creating more sophisticated and lasting interdependence.

Despite some setbacks, such as the suspension of specific projects in Chile or the freezing of Panama’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s commitment remains firm.

In fact, countries like Colombia have recently expressed their intention to join this initiative, despite open and direct pressure from Washington. This suggests a dynamic of interaction that is still active and adaptive between the Latin American and Caribbean region and China.

Taken together, these recent announcements demonstrate that China is not only strengthening its ties with Latin America but is doing so in a structured, diversified, and strategically focused manner.

The People’s Republic of China projects itself in the region as a long-term strategic partner that not only strengthens existing ties but also reinforces them with a comprehensive and multisectoral vision.

The activation of new cooperation programs, the increase in strategic investments, and the diversification of economic, cultural, political, and security ties reflect a clear intention to consolidate a China-Latin America axis with its own identity, independent of traditional geopolitical pressures.

What the numbers show

The figures presented in the European Parliament’s Feb. 25, 2025, report clearly reflect China’s geoeconomic repositioning in Latin America.

According to the document entitled “China’s Growing Presence in Latin America: Implications for the European Union,” China has established itself as the third most relevant player in the region, surpassing the European Union (see the following graph) and placing itself only behind the US. Since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has intensified its presence through a robust network of bilateral agreements—nearly 1,000 to date—covering strategic sectors such as mining, energy, and agriculture.

European Union data shows China’s rise in trade with Latin America and the Caribbean. Photo: European Parliament.

One of the key drivers of this expansion is the Belt and Road Initiative. Since 2018, it has become the main channel for promoting infrastructure projects and economic cooperation in Latin America.

An infographic published by Inter American Dialogue/Ruiyang Huang highlights the main infrastructure projects financed or directly invested in by China in the region.

China is making massive financing and investments in infrastructure in the CELAC region. Photo: Inter American Dialogue/Ruiyang Huang.

However, these data do not include other major projects in which Chinese companies are involved, such as the Bogotá Metro, built by China Harbour Engineering Company Limited (CHEC) and Xi’an Metro Company Limited (Xi’an Metro), with resources provided to the Colombian government by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

It’s worth noting that the IDB, clearly dominated by the US, has been the subject of controversy after the US State Department opposed its financing for this Colombian initiative in collaboration with these Chinese companies. This underscores the magnitude of the struggle over Colombia as a geopolitical space.

On another note, trade between China and the CELAC region has reached record levels, with bilateral volume exceeding $500 billion by 2024, while China is consolidating its position as a priority market for Latin American exports of copper, soybeans, oil, and gas.

China is looking to Latin America and the Caribbean for products it considers strategic, but is also positioning its goods and services at the same time, increasing its market share.

As the European report notes, the US’ shift as the region’s main economic partner is progressive and notable.

This could be explained by the loss of installed industrial capacity in the US, geopolitical reasons, and the shift by CELAC countries in search of more advantageous relations.

The COVID-19 pandemic also fostered the development and diversification of ties. China sent over 300 million doses of vaccines and nearly 40 million units of medical supplies to the region, strengthening its image as a supportive and humanitarian power.

South America stands out

In 2023, this forum conducted research focused exclusively on South America, aiming to diagnose the evolution of trade between this region and China using a comparative method that also considered the behavior of trade with the US.

This analysis revealed a quantitative leap in South America’s trade relationship with China, highlighting the particular case of Brazil, whose specific weight as an economic and industrial engine has been decisive in the direction of regional trade flows.

The study took 2010 as its starting point, a period in which a progressive consolidation of Chinese foreign policy toward Latin America was already evident. It was driven by key doctrinal precedents such as the publication of the first official Chinese document on Latin America and the Caribbean in 2008, and the implementation of the Cross-Border Trade Settlement Pilot Program for the Yuan in 2009, the purpose of which was to advance the internationalization of its currency.

Based on these milestones, 2015 stands out as a turning point in South American foreign trade, as the trade curves between China and the US cross, according to the graphs analyzed.

This change coincides with the International Monetary Fund’s recognition of the yuan as part of the Special Drawing Rights basket of currencies, which consolidated the Chinese currency as an official currency alongside the dollar, the euro, the yen, and the pound sterling.

That same year, the First Ministerial Meeting of the CELAC-China Forum took place in Beijing, ending with the adoption of the China-Latin American and Caribbean States Cooperation Plan (2015-2019), a roadmap that deepened regional integration within the Belt and Road Initiative. Since then, China’s rise in trade with the South American region has become more noticeable and sustained.

Photo: Misión Verdad.

Photo: Misión Verdad.

In contrast, an analysis of trade flows between the US and South America shows a downward trend since 2014, with an even steeper decline during Donald Trump’s first administration. The imposition of unilateral sanctions against Venezuela, a key country for its oil reserves, marked a turning point in the economic relationship with the region.

This decline in trade is also related to the lingering effects of the 2008 global financial crisis, of which the US was the epicenter. Added to this were factors such as falling commodity prices, growing global competition in goods and services, and the new financial facilities offered by China, which, as mentioned above, have had a significant impact on the infrastructure associated with trade activity.

From 2016 onward, Chinese exports to South America began to systematically outpace those of the US. This lead widened, especially starting in 2019. Regarding imports, China has maintained a consolidated lead since 2016, while the US experienced a continuous decline since 2018, failing to recover the record lows reached since that year until at least 2022.

This pattern reflects a structural shift in the region’s trade ties, with a sustained shift toward the Chinese market and investment.

China’s demand for raw materials such as soybeans, food, and oil has significantly benefited the Brazilian economy. In the case of iron, it is vital for the steel industry in China. Meanwhile, the trade conflict between China and the US during the Trump administration led to a reorientation of agricultural trade toward Brazil, particularly soybeans, consolidating its position as a strategic supplier.

On the other hand, 2025 marks the 20th anniversary of the first free trade agreement (FTA) between China and a Latin American country—a pioneering agreement signed with Chile in 2005.

This milestone marked the beginning of a new era in the biregional relationship, characterized by increasingly structural, diversified, and strategic economic cooperation. Since the agreement came into force, bilateral trade between the two countries has increased exponentially: from approximately $2.3 billion in 2002 to $56.91 billion in 2023, representing a nearly 25-fold increase in two decades.

This momentum has led China to consolidate a network of free trade agreements with five countries in the region: Chile, Peru, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Nicaragua, thus strengthening its position as a key economic partner for Latin America.

This expansion strategy was framed within China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), which prioritized strengthening ties with countries in the Global South, particularly with the CELAC region.

This approach promotes principles such as sovereign equality, mutual benefit, economic openness, technological innovation, and people-centered development, aligning trade advancement with China’s long-term foreign and development policy objectives.

In addition, China maintains a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Venezuela, one of the few of its kind between China and other nations in the world, reflecting the exceptional and priority nature of the bilateral relationship.

This alliance, officially established in 2023, was ratified in May 2025 in Moscow through a meeting between Presidents Nicolás Maduro and Xi Jinping.

This translates into multifaceted cooperation spanning sectors such as energy, infrastructure, technology, communications, food, aerospace, and economic development. Together, these elements demonstrate Latin America’s privileged position in China’s international projection, as well as Beijing’s interest in consolidating a solid South-South cooperation framework that can be leveraged in the face of external geopolitical pressures.

In this context, the renewed tariff offensive launched by Donald Trump during his second term, which has included punitive increases on strategic products, technological blockades, and threats of secondary sanctions, confirms the trend of an aggressive return to economic protectionism in the US.

Washington’s highly aggressive and zigzagging tariff policy is multidirectional. It applies to China but also creates new obstacles for relations between CELAC countries and the US. This creates additional opportunities for China and the CELAC nations.

Faced with this reality, President Xi Jinping firmly warned that “there are no winners in tariff or trade wars. Intimidation or hegemony only leads to self-isolation.” With these words, he made it clear that China will not give in to unilateral pressure from the Trump administration, and that it will continue to strengthen its cooperation with Latin America and other regions on the basis of “equality, mutual benefit, innovation, openness, and well-being of the people.”

Reiterating that independence and autonomy are a “glorious tradition” of the Latin American and Caribbean peoples, Xi called for “jointly defending the sovereign right to development” and resisting pressures that seek to “fragment international trade and condition financing on political alignment.”

China’s commitment to a community of shared destiny with Latin America not only challenges the dominant unipolar paradigm but also strengthens the Global South’s capacities to jointly confront the challenges of this defining transformation of the century.

(Misión Verdad)