Telesur’s Brian Mier on Brazil Presidential Elections: There Is No Evidence of Vote Stealing in the First Round

OCTOBER 17, 2022

Poster with details of the interview and a photo of Lula Da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro as a watermark. Photo: Orinoco Tribune.

Caracas, Oct 16, 2022 (OrinocoTribune.com)— In a special to OT’s continuing coverage of Brazil, editor Jesús Rodriguez-Espinoza recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Chicago ex-pat and now São Paulo-based journalist Brian Mier.

Mier is a Telesur English correspondent in Brazil and co-editor of Brasil Wire. Having lived in Brazil for almost 30 years, he is a leading voice on Brazilian issues for English speakers worldwide.

During the interview, we discussed the most pressing issues in the upcoming election. We summarize some of his responses and provide a transcript of the whole interview below.

1- Possible electoral results, taking into consideration recent important endorsements of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, like those from Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet, along with recently raised accusations of vote stealing and the manipulation of religion to favor Bolsonaro.

If the elections were today, Lula would win, but there are two weeks until the second round. The endorsement from Simone Tebet, who finished in 3rd place and is now actively campaigning with Lula, will provide the necessary votes to secure Lula’s victory. In the case of Ciro Gomes, the scenario is not as clear. Many poll experts in Brazil have pointed out that Gomes’ attacks against Lula during the final days of the campaign before the first round ended up helping Bolsonaro; many believe his supporters are going to split 50/50.

For Mier, there was no evidence of vote stealing during the first round. However, there was significant evidence of Bolsonaro’s social media campaigns using illegal funding from economic powers in an attempt to influence voters, particularly those in the evangelical groups. He explained that evangelical groups are the more active support base for Bolsonaro, but they only represent 31% of the population, and Lula still has considerable support within that demographic.

2- Balance of power within Brazil, paying attention to the balance of forces within Congress, the military, media, and the real relevance of grassroots movements.

In relation to the balance of power within Congress, the journalist explained that the Workers’ Party increased its presence in Congress and that Lula is accustomed to dealing with a Congress where he does not have a majority. To Mier, there are misunderstandings of this issue, especially among analysts outside Brazil. Concerning grassroots movements, he highlighted the gains of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), which gained six seats in state and federal congresses, and the work they are doing canvassing and cultivating the push for Lula’s victory in the second round. The endeavors of the Workers’ Party (PT) and its machinery are also notable, organizing massive mobilizations far exceeding Bolsonaro’s.

In connection with the military, Mier remarked, the autocoup narrative was launched by Bolsonaro himself. Referring to an internal military study that was leaked in Brazil’s press, he said that there may be support for this risky endeavor from the Air Force and the Navy, but not from the Army, which is more powerful than the two other forces combined. In Mier’s view, even the support that Bolsonaro has within state military police has been diminishing, making the autocoup scenario less likely.

On the topic of media, the co-editor of Brasil Wire noted how the Brazilian media is still embedded in the military dictatorship of the 60s and, thus, in the economic establishment. Even though Mier believes that media support for Bolsonaro has been decreasing because his project has been different from what was initially expected, some in the media have been showing support for Lula while they prepare the ground to attack him eventually.

3- International developments’ impact on the electoral debate, and the impact of Lula’s possible victory on the return of progressive governments in Latin America. Prospects of new lawfare campaigns against Lula.

On this particular point, Brian Mier referenced the attacks that leftist leaders, such as President Maduro in Venezuela, receive from the international left, which he sees as connected to academic Trotskyist circles in the United States who also attack Lula. He mentioned Lula’s comments on the alternation of political power and how the media has twisted them to make them sound like an attack on Nicolás Maduro and Daniel Ortega. However, Lula generally tries to be very respectful of the internal political affairs of these countries.

(Video at link)

Looking back, Lula’s relationships with the so-called “axis of evil” countries like Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela were always very positive and constructive. A high point was during the 4th Summit of the Americas in Mar de Plata, Argentina, in 2003, when Lula and Hugo Chávez buried the US-led initiative known as the “Free Trade Agreement for the Americas” (FTAA). Mier added that unlike Venezuela, the military in Brazil doesn’t have political training in the military exists, .

According to Mier, “Lula’s victory would be good for the sovereignty of peoples in Latin America, especially in South America, and it would be a move forward for the continent in general.”

Considering that Brazil is a domestically-focused country, partly because of the linguistic barrier of being a Portuguese-speaking country surrounded by Spanish-speaking countries, Mier believes that Brazilians are not caught up in Washington’s New Cold War narrative against China and Russia. He expects that this position will continue under Lula.

When asked about the possibilities of restarting or reshaping lawfare attacks against Lula, meaning initiating weak and bogus judicial charges to disqualify him, take him out of office, or disqualify him from any political race, Mier clarified that all the charges used against Lula in the Lava Jato (Car Wash) case have no chance of being restarted. However, that does not affect possible attempts of other kinds. The Telesur English journalist believes that Brazilians are tired of this drama.

Our editor thanked Brian Mier for accepting the invitation and giving such an informative talk while acknowledging the immense respect that Orinoco Tribune has for Mier’s work, to which he responded that he is also a big fan of Orinoco Tribune.

We encourage all our readers to read, follow, and support Brasil Wire.

Transcript

Welcome everyone, today we have an interview with Brian Mier directly from Brazil, and it’s an honor for us to have him here. He has been a correspondent for Telesur English in Brazil, and he is also a co-editor of Brasil Wire. He also is the editor of the book “Year of Lead: Washington, Wall Street, and the New Imperialism in Brazil,” and he also has been living in Brazil for more than 25 years.

Welcome, Brian. I will just jump into the first question, which is basically, who do you think is going to win? Taking into consideration the recent endorsements of Gomes and Tebet to Lula, but also taking into consideration the “stealing of votes” debate that has been arising after the first round, and also the religious debate within Brazil that I understand is very influential in people’s decisions. So, welcome again, and you can jump into the answers.

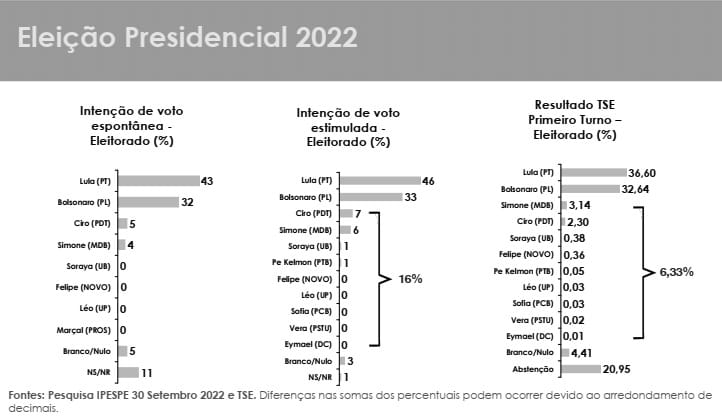

You know, a lot can happen in two weeks. If the election were held today, Lula would win. You know, Lula won the first round by over 6 million votes—6.2 million votes. It was the first time since the return to democracy in 1985 that a challenger beat the incumbent president in the first round of an election.

The media spun it as much more negative results than expected. There were some surprises: Bolsonaro did a little bit better—about six points better—than he was appearing in the polls, and some of the gubernatorial races where the left didn’t do as well as planned. But the left, now specifically the PT, the Workers’ Party, picked up a 21% increase in members of congress and picked up, since 2019, a 50% increase in number of senators, so there was some, you know, in general, it was positive.

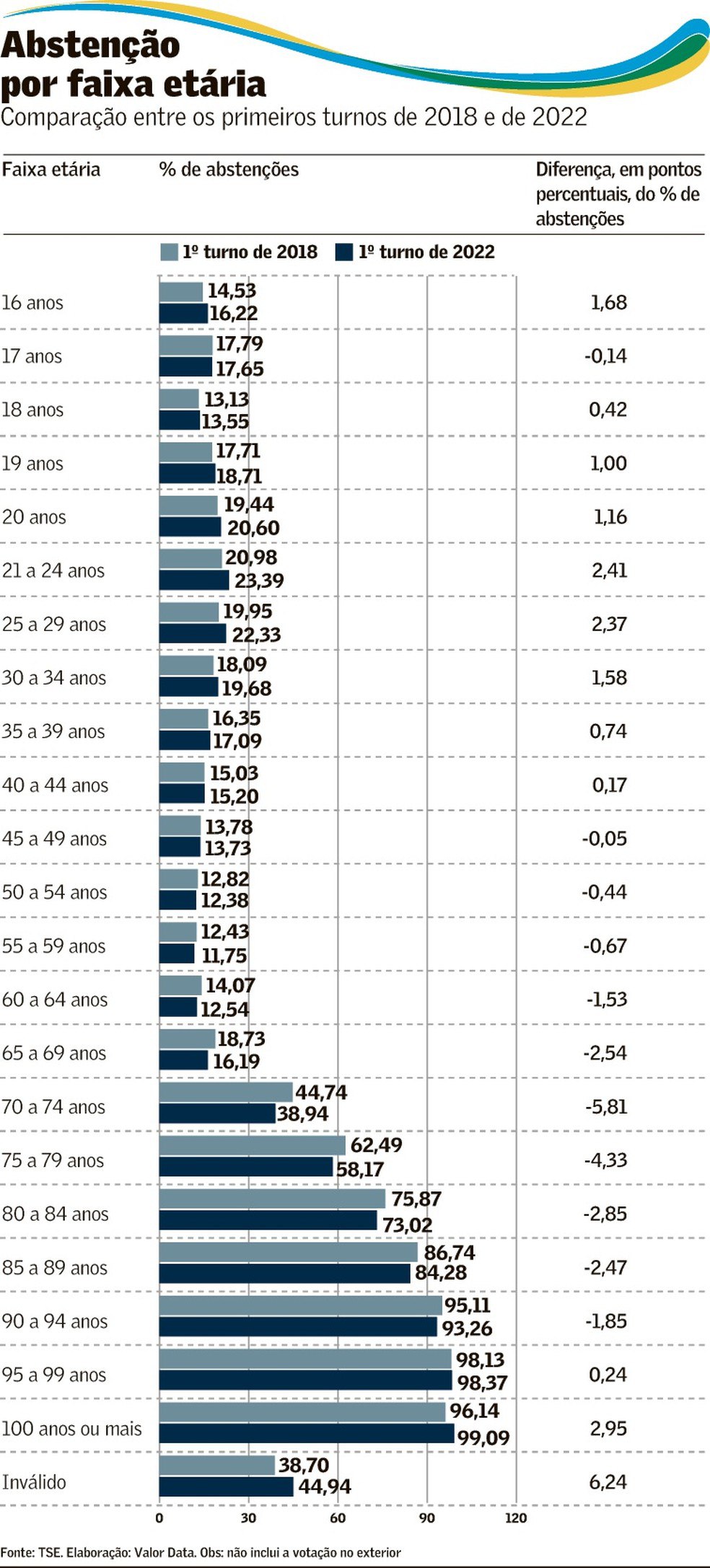

There were a few disappointing results, like Haddad for governor. He was expected to win—to lead—after the first round, but he ended up behind Bolsonaro’s candidate. Anyway, Lula only needs, like, 1.6 million votes to win. Simone Tebet, who came in third place, she had about 5 million votes total, and she’s now endorsing Lula; she’s campaigning with him, she’s going to campaign events, and is very enthusiastically supporting Lula. So just from her votes, even if Lula got half of her votes, it would be enough to win in the second round. Unless there’s a major change in the number of abstentions, or something like that. If a lot more people abstain, that would help Bolsonaro.

Ciro Gomes has been more negative than positive. In fact, one of the explanations for the surge in votes for Bolsonaro at the last minute is that Ciro Gomes’ support—he was polling at, like, seven or eight percent, and he ended up with three percent of the votes—the director of one of the largest polling agencies thinks most of those votes went to Bolsonaro. And the reason is that Ciro spent the last two months running really dirty attack ads against Lula instead of going after Bolsonaro, and some of these ads even use this “fashwave” graphic style, which is popular with the international far right. So it’s hard to say what’s going to happen with his remaining votes; the people who did vote for him—he ended up with, like, three percent—but most people think it’s gonna split about 50/50. At this point, between Lula and Bolsonaro, that wouldn’t be enough for Bolsonaro to win.

In terms of vote stealing, there’s no evidence that any votes were stolen. What there is a lot of evidence of is the illegal use of WhatsApp and other social media applications targeting specific demographics, with illegal campaign funding from corporate sectors: from bourgeoisie comprador elites in Brazil that target, for example, evangelical Christians heavily with disinformation, such as, “If Lula’s elected, he’s going to change all of the bathrooms in the public school system so that anybody can use them regardless of gender,” or that “he’s going to close down all of the Evangelical churches.” So this is causing some problems; however, it’s important to remember that evangelicals are only 31% of Brazil’s population. They’ve been Bolsonaro’s main support group for the last four years. However, his support has been slipping among that demographic, despite all of the fake news campaigns. Lula basically doubled support of the evangelical population for the Workers’ Party through a lot of base-level organizing. It’s not hard to pull out lessons from the Bible and explain how Jair Bolsonaro is not acting like a Christian.

It’s good that you clarified that because I was worried about the whole issue, especially the vote stealing that has been coming up in recent days, especially after the first round, of course, so it’s good to know that there was no real concern on that particular issue.

Bolsonaro created a special military commission with the intention that they would prove that there was some vote stealing going on. Because Bolsonaro is pushing this narrative that the electronic voting system is susceptible to fraud, which it’s never been connected with any kind of fraud, proven. And even his own hand-picked commission of military people was unable to prove one case of fraud. So the real fraud that’s happening is manipulating the public opinion illegally, using illegal tactics, but not the actual voting process.

Let me jump now to the second question, which is connected to the balance of power. And in that particular area, there are different institutions that one has to analyze. The one that concerns me the most is the balance of power in congress after the elections. After the first round I mean, and also the grassroots movement, how strong are the grassroots movements in Brazil in helping Lula to win, if you see a connection there? And of course, the military and the media, but everyone knows how it works. But anyway, it’s good to hear it from someone from Brazil.

In terms of grassroots mobilization, Lula has been putting hundreds of thousands of people on the streets in city after city. He was in Salvador the day before yesterday, and over 150,000 people were on the street behind him. And this is due a lot to the base of the Workers’ Party, which is labor unions and social movements.

So for example, the Landless Rural Workers Movement, the MST, is the largest social movement in the Americas—the largest working-class social movement. And they have been on the streets. For the first time in its history, the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement, or the MST—they fielded 15 candidates for state and federal congress. They’ve never been able to—they’ve never tried—there’s been a few incidents in the last 40 years when they’ve fielded one or another candidate; it’s always been hard to mobilize the vote in rural areas, right? This time, they managed to put six MST members into federal and state congress[es], which is a historic first. And they’re going to be, you know, all of those apparatus are canvassing for Lula right now, working for Lula, all of the vote, all of the political organizing operations that they set up for their candidates.

Brian, in comparison with those movements, I mean the PT machinery and the MST, does Bolsonaro have a counter response in social movements that support him?

Well, if you look at the crowds on the streets, he’s not able to put many people on the streets. Like, you see some images of him in front of these huge crowds, these are large religious events that would have happened anyway that he appears at. For example, the national March for Jesus, which is an evangelical holiday—ironically, that was declared a holiday by Lula, when Lula was president—that every year brings hundreds of thousands of people to the streets of São Paulo. And so Bolsonaro appeared at that event, and he’s using the footage in his commercials as if that was a rally for him. His actual rallies are much smaller, but a lot of his support is through evangelical churches and evangelical pastors. So you could say that was, that that’s his main support base. As well as the military police officers and things like that; there’s no labor unions supporting Bolsonaro.

What about the balance of power in congress? I read somewhere that he is not going—if Lula wins, he’s not going to have an easy task in that particular area.

Yeah, I think this analysis is based on a misunderstanding of Brazil’s congress. During the height of Lula’s first government, the Workers’ Party never had more than 25% of the seats in congress, and they never had more than 14 senators out of 81 total members of the Senate. So with those numbers, you add on the close allies, which is the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB), and this year, the Green Party (PV) has joined as well, and REDE—very small parties. But even if you add all of the allies, even if you add PSOL, which is a traditional ally in congress with the PT, they have a total of a little over a hundred members of congress in a congress of 514 people.

The important thing is that the number of congress members increased by 21%, back to the level that it was at during Dilma Rousseff’s presidency. So it’s hard to spin this as a negative, as the foreign press is trying to do, when they [PT] actually increased seats both in the house and in the Senate. Now, when Lula was president, he had to do a lot of things by executive order, by decree. And then also, he had to make alliances with center-right parties in order to govern. This led to a lot of criticism from bourgeois vanguard leftists, you know, from Brooklyn or something, saying his government was neoliberal when, in fact, if you look, the Workers’ Party is much farther left than any Workers’ Party government has ever been because of the need for these coalitions to govern.

Unfortunately, or fortunately—however you want to look at it—Brazil has a very large middle class, and you can’t govern the country, unfortunately, just for the working class in this type of capitalist system that Brazil has. Short of an armed revolution or something like that, it would be impossible to govern without some of these center-right parties, which trace their roots back to the military dictatorship. There was amnesty for everyone, and they allowed all of congress and Senate to remain in power after the end of the dictatorship, so they just created two new political parties: (P)MDB and PFL.

PFL changed its name several times, but it’s still the second biggest party in the senate in congress; it’s called União Brasil now. This was the official political party of the neofascist military dictatorship. And the official opposition party, the MDB, is the party of Simone Tebet, who just came in third and who’s now supporting Lula. Unlike, for example, Argentina, where they put former generals in jail and things like that, they’ve never really fully transitioned back from dictatorship to democracy in Brazil. You can see that, for example, in the behavior of the military police, who don’t have to follow the rule of law in Brazil; they have their own internal court system. So this is what makes the situation really complicated and easy to misinterpret. It’s easy for someone who—living in the United States or something, who’s never lived under a left-wing government—to just say it’s neoliberal or something.

That happened a lot with Lula during his first two terms, that’s true. So the military is a more complex stadium, according to what you were just saying, right? And what about media?

Let me get into the military really quick. There was an internal issue: as you know, in the last year and a half, Bolsonaro has been threatening to hold an autocoup if he doesn’t win the elections. So the defense department did an internal study of the military to see which branches of the military leadership would support Bolsonaro in a possible autocoup attempt, and the results were leaked to the media, and they’re kind of surprising. First of all, the navy and the air force would support Bolsonaro if he tries to hold a coup, but the army would not, according to this internal study. The army is bigger than the navy and the air force combined. And the other surprising thing was that most state military police apparatus or leadership would not support a coup attempt by Bolsonaro. Everyone thought that he had all of the police in the palm of his hand, and it doesn’t look like it. And one of the police apparatus that is most anti-Bolsonaro right now is Rio de Janeiro state military police, which are the most corrupt and worst police organization in Brazil. So he can’t even hold on to his own, and he’s from Rio, his family has connections in the militias, which are all off-duty police officers. So it looks like there’s some kind of internal organized crime struggle going on inside the real military police which isn’t favoring Bolsonaro right now, either. So that was just interesting to see.

Now with the media, I don’t normally recommend or support or anything Reporters Without Borders, it has a reputation of being a CIA front group. Nevertheless, they issued a report about five years ago called “The Land of Thirty Berlusconis” about Brazil’s media, and the report was actually pretty good. Basically, you have a small number of very powerful elite families who control all of the mainstream media in Brazil.

Globo, for example, its television system was built during the military dictatorship in partnership with Time Warner Corporation specifically as a means of social control over the population. So they didn’t just install all of these transmission towers all around Brazil and gave the license to Globo; they then bought back all of the shares: they helped Globo buy back all of the shares from Time Warner two years later by giving them billions of dollars in advertising on their network. And so this network has always been very pro-military. They only started calling the 1964 coup d’etat a coup in 2014. Before that, they’d always call it a “democratic revolution,” and this is the third or fourth-largest open-air TV network in the world. So even they have turned on Bolsonaro.

These traditional media groups like Globo, Folha de São Paulo, O Estado de São Paulo [Estadão] all created the conditions for Bolsonaro to rise to power through years and years of slander and character assassination of leftists, especially Lula, but also Dilma Rousseff, PT President Gleisi Hoffmann, who went to Nicolás Maduro’s last inauguration. They’ve [traditional media groups] been attacking people like that almost every day. And so finally, when this monster spins out of control, their final result wasn’t someone like Bolsonaro; they were looking for, as they said in Brazil, the kind of fascist that eats with a knife and a fork. They didn’t want this out-of-control monster like Bolsonaro in power. So now, they’ve backed off their support for Bolsonaro. They’re ostensibly supporting Lula, but they’re already setting the groundwork to destabilize his government to guarantee that the right-wing maintains control of the macroeconomics, basically.

This is very interesting, what you are saying. You’re giving me another perspective of Brazil, I mean the elections. Let’s jump to the last question. It is basically connected to how international developments might impact the electoral results in Brazil. But maybe also the counter-analysis might also be of help, I mean how a possible victory of Lula might impact the region, at least Latin America?

I think that there’s this kind of false “spectrum war” going on against the Latin American left. So you get people from all sides of the spectrum attacking Nicolás Maduro. You have these people attacking Nicolás Maduro from the so-called left, but you’re like, what’s their popular connections and left? Nothing. Sometimes, it’s, like, Trotskyist academics from the United States. And you have the same thing happening against Lula the entire time.

One thing that’s been taken out of context is a few comments he’s made, unfortunately, about how he believes that there should be an alternation of power in Venezuela and Nicaragua. These comments are always taken out of context, because his main point, whenever he’s asked about these countries, is that the people of those countries should solve their own problems. It’s not [his] position to suggest what they should or shouldn’t do, [his] personal opinion is this.

If you look back at the history of the relations between the Workers’ Party governments and the rest of the Latin American left, including Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia, all of this so-called “axis of evil” of the United States, they always had very good relations.

I’d like to highlight the time that Lula and Hugo Chávez defeated the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA) together. That was important. Now, one of the differences between Venezuela and Brazil, obviously, is that the military in Brazil really dislikes the left; they’ve never been able to do political formation of the military or something, so I think that’s a very strong thing in Venezuela’s favor.

In general, I think Lula’s victory would be good for sovereignty of peoples in Latin America, especially in South America, and it would be a move forward for the continent in general, just because it’s such a big country; it has such a big economic influence on the rest, on international events.

In fact, in Brazil, do you think that might happen? I know that Brazil is like a self-centered country that is sometimes…

The language isolates it. Even though we have these neighbors everywhere, most Brazilians don’t understand Spanish, so it’s unfortunate. But one thing that’s interesting is that nobody in Brazil got on board with, nobody is getting on board with the new Cold War. If you look at Russia and China, even Bolsonaro’s supporters, not Bolsnaro himself, but his people behind the scenes in the Brazilian State Department are refusing to give any kind of lip service to the United States on China and Russia, and that will continue under Lula.

When Bush asked Lula for Brazil to join the Iraq War, he [Lula] said, “Our war is against poverty, it’s against hunger. We’re not getting involved in other people’s wars.” So I think the US government has been trying to put the Bolsonaro administration against Venezuela, we know that. So it’ll be good for Venezuela if Bolsonaro’s out. He’s been doing joint military operations with the US military in Brazil near the Venezuelan border as a kind of intimidation tactic; that will end if Lula was elected. I mean, he’s not going to have a really far left-wing government because of all of the compromises he’s had to make to get the endorsement of different people in the bourgeois elite, but it will be geopolitically much better for Latin America in terms of sovereignty of nations to have him in power than to have someone who is just the most sycophantic Brazilian leader in history to the United States. He, Jair Bolsonaro, even visited CIA headquarters after he was elected. The first time a Brazilian president’s ever done that.

It’s crazy. Let me ask you one final question: what about lawfare? Do you think that they will retry those things [if] Lula wins?

Those cases against Lula cannot be retried anymore. I mean, when the media said that it was thrown out on a technicality, they didn’t follow through. The only reason they could call it a technicality is because the Supreme Court ruled, but these cases had been illegally forum shopped [assigned] to a sympathetic judge in a jurisdiction that didn’t have any authority to act on those charges, which detailed crimes that were committed in a different state. So they recommended—first of all, they said all of the evidence had to be discarded. There wasn’t much evidence to begin with, it was just a few coerced plea bargain testimonies, but they had to be discarded.

If prosecutors wanted to try and recharge Lula for any of those crimes, that had to happen in Brasília Federal District courts. What happened is that on all of the charges, public prosecutors attempted to reinitiate the charges in Brasília, and in every case, they were immediately thrown out for not having any material evidence, because none of these charges ever had material evidence behind them. So there’s no way he could be tried for any of those frivolous 26 charges that the United States Department of Justice backed, that the Operation Car Wash team levied against Lula. That’s done with. They’d have to invent something else.

But I think that people are tired of this lawfare now; I don’t think they’d be able to get anything to stick on him at this point. Especially since the first time they tried to throw out Lula with lawfare over this scandal called the Mensalão, which was equally ridiculous and without any kind of evidence, [same] as Operation Car Wash. From that moment forwards, the Workers’ Party has been extra careful about making sure they don’t do anything illegal because they know they’re under, like, heavy scrutiny the entire time. They have double or triple the level of scrutiny of any other political party. I’m not saying there’s no corruption with any Workers’ Party official, but they’re much more careful about it than the other parties.

That’s why after years and years of investigation, the best that Operation Car Wash could come up with was one coerced plea bargain testimony of an imprisoned corrupt businessman who got millions of dollars in asset retention and an 85% sentence reduction in exchange for reading off the script to implicate Lula; he changed his story three times before they let him out of jail. That was the only thing they did. They threw out [Judge] Sergio Moro, who presided over the investigation—his own investigation. He rejected 100, over 100 defense witnesses of Lula’s. I mean, if you look into those cases, it’s such a ridiculous travesty of justice. I don’t think they’re gonna try that again; they might, but I don’t think it will stick.

I think the big problem is that he’s [Lula] gonna have to put—it’s going to be like 2003, 2004 all over again, when he was stuck in these IMF conditionality agreements from his predecessor, and he couldn’t increase funding on education and health and sanitation until he paid back the IMF loan early. So the first year or two is going to be tough, that’s my take. If he’s elected, of course.

It is good to know that, and it was very good to talk to you. Do you feel that overconfidence among Lula supporters is going to have an effect?

I think people might have been a little bit overconfident in the first round, because the media made it look like he was going to win in the first round even though that was based on a misinterpretation of polling numbers that didn’t take into account the margin of error. I mean, the big pulse at 50%, two-point margin of error either way. So we ended up with 58.4%: within the margin of error. I mean, the odds were that he wasn’t going to win in the first round, and the media made it look like he was. So that caused some overconfidence.

I think people are really worried now, and I think turnout among the poor and working classes can be higher in the second round than it was in the first round.

That’s good to know. Exactly, that will help mobilization of people, if they get rid of that overconfidence.

Thank you Brian, I really enjoyed talking to you finally, and a lot of respect for your work!

You guys too, I’m a fan of your work!

Orinoco Tribune special by staff

https://orinocotribune.com/telesurs-bri ... t-round-2/

******************

Rio de Janeiro: City of Militias, Gospel and Electoral Disputes

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on OCTOBER 18, 2022

Marco Teruggi

Lula visited the Complexo do Alemão favela. . Image: EFE

Lula visited the Complexo do Alemão favela. . Image: EFE

“I am the only candidate who has the courage to enter a favela without a security vest”, said Lula.

Rio de Janeiro is impressive. Few metropolises were founded on such beautiful landscapes. There are the green hills that border the sea, the Corcovado Christ on the top, the streets that lead to the beaches of Copacabana, the Selarón stairway with colorful ceramics in the Lapa neighborhood. During the nights of this month of October, the big tropical moon can be seen over the Botafogo inlet at the foot of the Sugar Loaf, and the samba schools, such as Estácio de Sá, prepare for the upcoming carnivals: they play, dance, compete internally, invoke saints from many skies until the early hours of the morning.

The postcards of the south zone or the center of the old Brazilian capital are however a surface, the illuminated edge of an unequal and violent city. It can be seen in the number of people surviving in the streets; in a geography where in any corner a favela emerges; in the kilometers of slums and broken landscapes when taking a train to the west of the city; or by the marked territorial control of armed organizations, both narcos and so-called militias, which, among so many crimes, have murdered the young black feminist Marielle Franco in 2018.

“Most of the popular territories are dominated by militias, militarized groups, Pentecostal churches have hegemony, an important role of daily dialogue in people’s lives, there is a great emptying of social relations coming from the State, popular councils, institutions not only of social participation, but of social agenda, people have no place of public debate, of meeting, those places are occupied in the territories by militias, drug trafficking or the church”, explains Tainá de Paula, councilwoman for the Workers’ Party (PT).

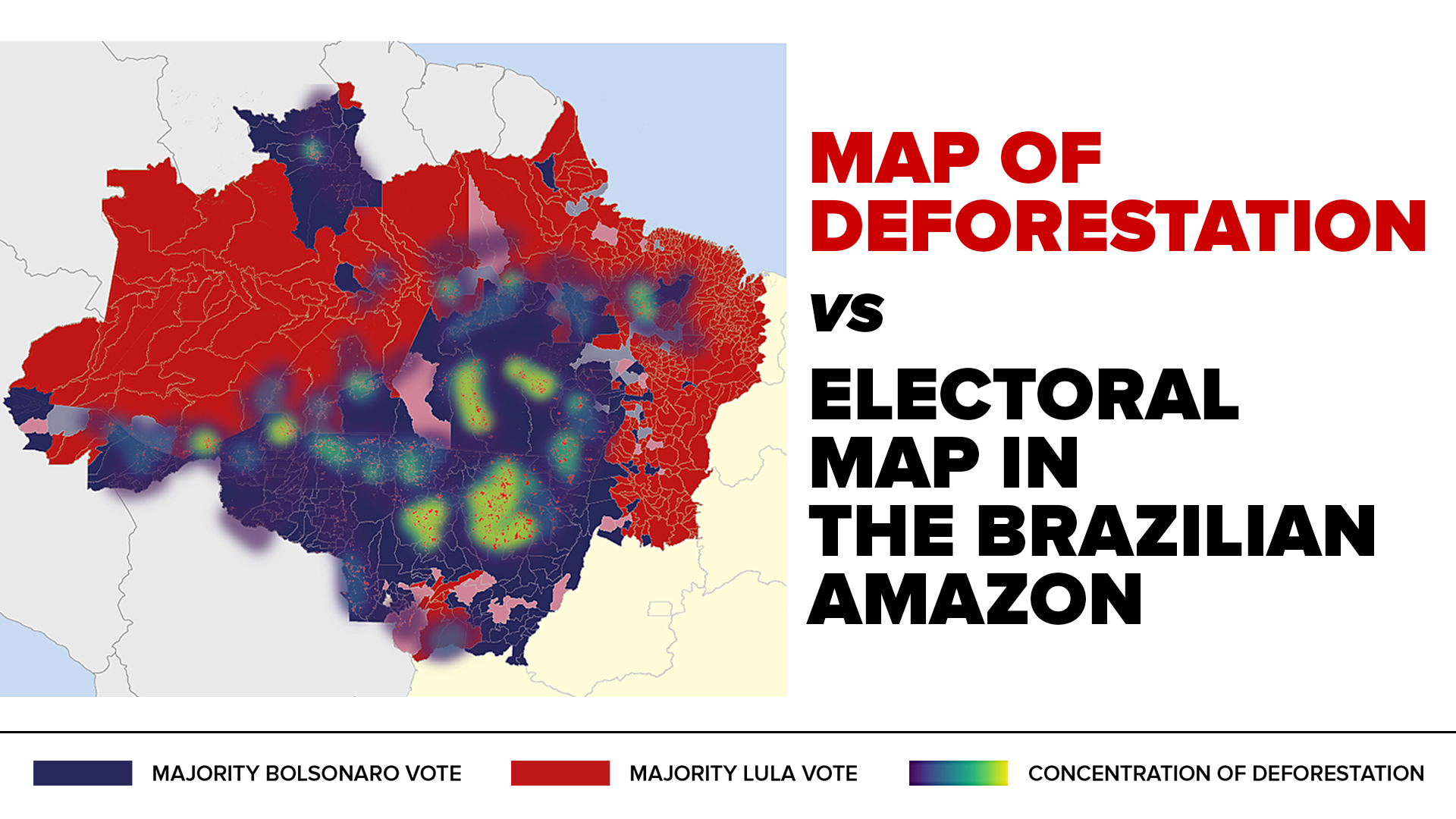

De Paula introduces herself as “a black woman from a favela, mother of a girl, survivor of the racist logics of Rio de Janeiro”, a state where 53% of the population is black. She is at a campaign table with flags, flyers, she is photographed making the L of Lula with her hand with those who pass by and support the former president. One fact worries her: “there is a very shocking map, comparing Bolsonaro’s vote in Rio with the map of occupation of the militias, it is 90% overlap.”

The vigilante militias

The electoral result gave the victory to Jair Bolsonaro in the state of Rio with 51.09% against 40.68% for Lula da Silva, and his candidate for governor, Cláudio Castro, reached 58.67%. The vote in the state of more than 16 million inhabitants was one of those that marked the map of southeastern Brazil favorable to the current president. In the city, Bolsonaro won in nine of the ten areas controlled by militias.

“The militias originally arose from extermination groups that operated from institutional police and firefighters who organized themselves after work, many with the perspective of supplementing income and bringing a false idea of security for territories without institutional police coverage,” explains De Paula. The militias grew and mutated from those 1970s to the present day: they went from focusing on armed security, to controlling services, charging to carry out activities, “they occupied the whole territory, almost a substitution of what the State should be.”

“More recently there was a closer relationship between the militias and drug trafficking, they began to join together and create what is called narco-militia, where there is a sealed agreement between drug distribution, protection of traffickers and territorial control, it is a junction that in my opinion and that of several scholars is out of control, because it is not known where one faction begins and where another ends”, explains the PT councilwoman, who places the presence or control of militias in 60% of the city.

“The political cadres campaigning for Bolsonaro are figures linked to these groups, they work allied to the militias, they operate in territories where most people cannot operate, how do they manage to enter those territories occupied by the militias?”. Bolsonaro “has no idea what the people of Rio are like because his life is linked to the militias that killed Marielle,” Lula himself said days ago.

The evangelical factor

Lula made this statement at the event held in the Complexo do Alemão favela, in the northern zone of Rio de Janeiro. It was the first act in the campaign in a favela of the city, at the tip of the morro, with half-finished houses, stairs to always higher, batucadas, euphoria for the presence of the former president sold in caps, towels, T-shirts and flags. “I am the only candidate for president who has the courage to enter a favela, without a security vest,” Lula told Bolsonaro a day later, on Sunday, during the debate between the two.

“Voting for Lula is not a sin” was one of the phrases heard from that stage of the Complexo do Alemão where Lula was accompanied, among others, by Wesley Teixeira, who heads a sector of evangelicalism that supports him. “I perceive in my bases a very strong presence of evangelicals, with a lot of difficulty to discuss without religion appearing as a rule, as a parameter. Lula is not an evangelical, and the fact that he is not an evangelical makes him impious, worldly, speaking in Christian terms, a difficulty for part of that sector that aligns and connects with that worldview to vote for him”, explains De Paula.

“It is a very difficult vote to turn around because it starts from the subjectivity of faith, not from a materiality of a theory, faith is the center of life and worldview. It is very important to modulate a speech to try to turn around some votes, but we have to focus primarily on those who are disenchanted with politics, they abstained, there is a very large presence of abstention in all cities and surveys show that here it can reach 20%, we have to focus on these people, they are disenchanted, but it is possible to sensitize them with what we are living, with hunger, misery”.

There are less than two weeks left in the campaign. Lula leads in the polls, and according to Atlas, the pollster that came close to predicting the result in the first round, the PT leader has 52.4% of valid votes against 47.6% for Bolsonaro. “I have the strong impression that we will win, but we will not have won Brazil. Brazil will be divided. What will be the size of our wisdom in approaching the different sectors, in building bridges, only time will tell”, concludes De Paula before continuing with the vertigo of the campaign.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2022/10/ ... -disputes/