Posted by Internationalist 360° on June 30, 2025

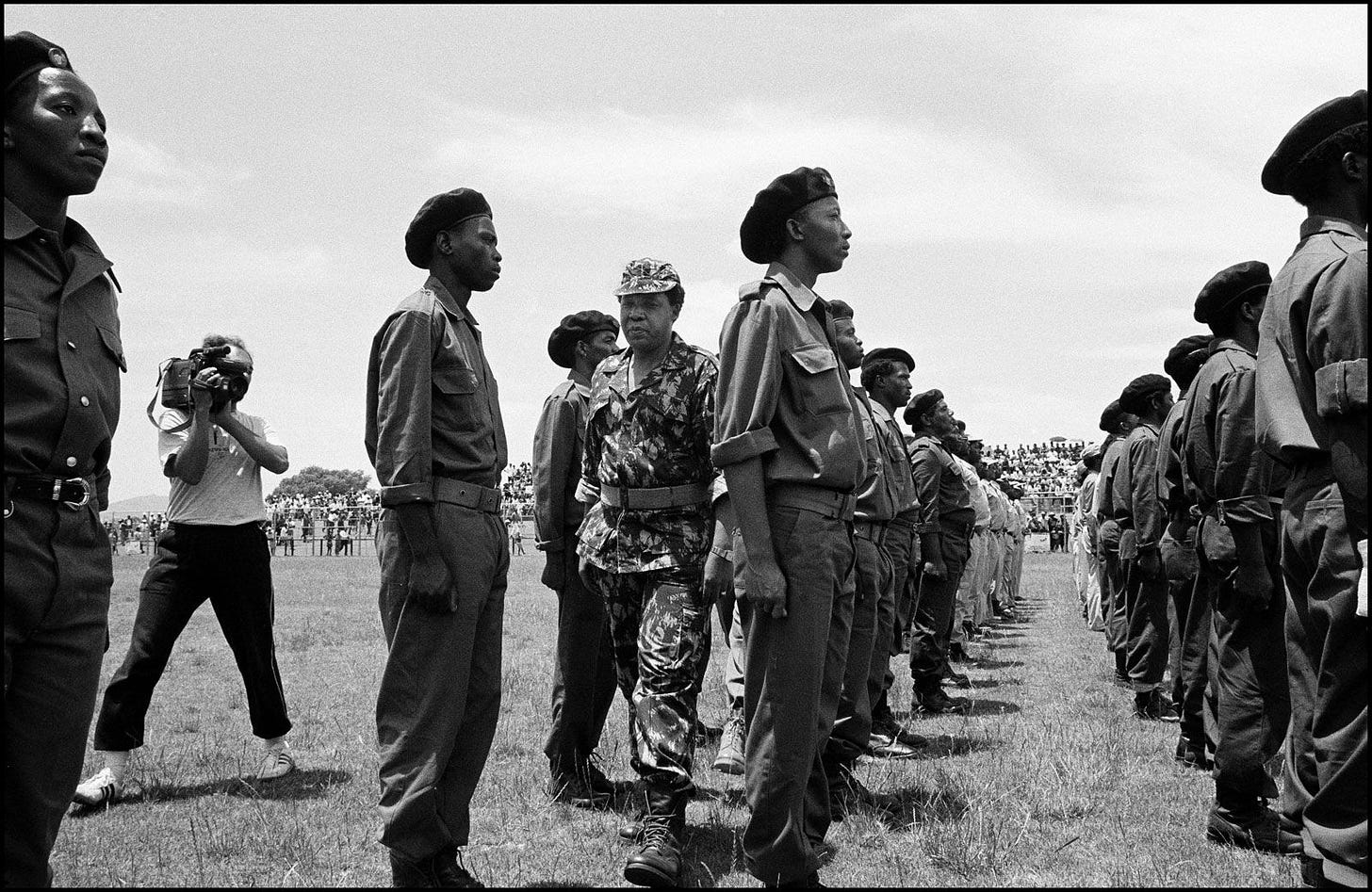

Smallholder farmers from various districts in Tanzania exchange knowledge and experience in ecological agriculture. Photo: MVIWATA

A Pan Africanism Today webinar featured discussions on socialist alternatives from South Africa and Tanzania on the 112th anniversary of 1913 Land Act in South Africa that alienated black South Africa from their own land.

June 19, 2025, marked the 112th anniversary of South Africa’s Native Land Act of 1913, widely considered the cornerstone of apartheid. Activists, land justice campaigners, and peasants came together in a continental webinar organized by Pan African Today to revisit the enduring land question in Africa. Titled “Land as a Source of Life: Socialist Struggles & Solutions”, the conversation featured Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM) President S’bu Zikode and MVIWATA Executive Director Stephen Ruvuga, and explored grassroots struggles and the implications of state policy on land access in South Africa and Tanzania.

Land and the legacy of apartheid

Framing the discussion was the theme that land is not a commodity but the foundation of food, identity, and dignity. The 1913 Land Act, which prohibited Black South Africans from owning land in most of the country, not only dispossessed millions but institutionalized racial segregation and economic exclusion. In 2025, more than a century later, this legacy remains largely intact.

S’bu Zikode, president of Abahlali baseMjondolo, was forthright in his critique of South Africa’s newly passed Expropriation Bill, which purports to allow land expropriation without compensation. “A lot of people will be misguided by this fancy expropriation act as if it is in the best interest of the working class and the poor,” Zikode stated. “We know from experience that the very same act will be used against the poor.”

According to Zikode, the law is being celebrated by elites while the actual material conditions of the poor remain unchanged. “This Act will replicate what the 1913 Act did: create a few Black elites and leave the rest of South Africa’s people landless,” he warned.

He noted that while the law gestures towards justice, in practice it is deeply exclusionary. “The government has no plan to help us access land, especially urban land. Thus, the landless have no choice but to continue occupying unused and vacant land.” For Abahlali baseMjondolo, land occupations are not criminal acts but acts of popular justice – redistributing land to the marginalized when the state refuses to.

Zikode reiterated that land is a matter of dignity and revolutionary democracy. “The land belongs to all. It should not be controlled by a capitalist elite, militarized municipal forces, or corrupt politicians. We believe land is a gift from God to be shared in peace and harmony.”

Tanzania’s path: from Ujamaa to neoliberalism

Stephen Ruvuga of Tanzania (MVIWATA) drew parallels with Tanzania’s land history, tracing it from pre-colonial communal systems to colonial dispossession under German and British rule. The colonial legal framework, particularly the 1923 Land Ordinance, institutionalized the state as the custodian of land and opened the door for capitalist exploitation.

Post-independence Tanzania initially pursued a radically different course. Under the Arusha Declaration and President Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa socialism, land was nationalized and reallocated for communal development. “It was the first time land became common, used by the people for food production and social harmony,” Ruvuga noted. Village councils were empowered to govern land use in a way that ensured widespread access.

However, the neoliberal turn in the 1980s and 1990s – forced by the IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programs – ushered in a new era of individualization and land commodification. “We moved from a system built on access and equality to one that serves markets and corporations,” Ruvuga said.

Recent years have seen international agribusiness firms and foreign governments acquire large tracts of Tanzanian land under the guise of investment and food security. “These programs, often claiming to solve hunger, have in fact displaced smallholder farmers, exported food production, and left many landless for the first time in our country’s history,” Ruvuga notes.

The decline of the Arusha Declaration’s ideals has coincided with increasing inequality and environmental degradation. “Neoliberalism has destroyed the very fabric that Tanzania was built on,” Ruvuga said. “Our justice systems, village governance, and cultural land ethics are under siege.”

A continental crisis rooted in capitalism

Across the continent, land remains a primary site of conflict between people and profit. Whether it’s urban evictions in South Africa or rural displacements in Tanzania, communities face mounting pressures from states aligned with capital.

Both speakers were clear, the fight for land is not just about legal reforms or policy reviews – it is about political power and class struggle. “When the landless become organized and recognize their own strength, the elite become afraid,” said Zikode. “They respond with violence, repression, and co-optation.”

Ruvuga echoed this sentiment, reiterating the need to resist externally imposed frameworks that turn land into a commodity. “Land must remain a source of life, not of speculation. The social value must come before commercial value.”

Toward socialist alternatives

The discussion made it evident that the land question cannot be resolved within the logic of neoliberal capitalism. Both Abahlali baseMjondolo and MVIWATA are advancing grassroots, democratic, and socialist alternatives rooted in the agency of the people.

As Zikode puts it, “We will continue to occupy land so long as the government has no clear plan to redistribute it. We will fight for land, and we will not compromise.”

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2025/06/ ... -struggle/

******

Let Us Cry for Our Beloved Country: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

The Sixteenth Art Bulletin (June 2025)

We honour the life and legacy of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1938–2025): revolutionary, writer, and prophet of the African soul. Remember his oeuvre, his exile, his fight and the future he envisioned

29 June 2025

[Listen to Wiyathi na Ithaka (‘Freedom and Land’), an anthem of the Mau Mau rebellion against British colonial rule, sung by Joseph Kamaru.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k60L715BE4I

‘Who are those singing? Why are they crying? They are singing for their hero coming from the forest’. Sung in Gĩkũyũ, these were the words that welcomed Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1938–2025) as he landed in his homeland of Kenya on 8 August 2004, concluding twenty-two years of exile. Thousands welcomed one of Africa’s most well-known anti-colonial and Marxist writers at the Nairobi airport. They sang liberation songs from the Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960) against British colonialism, a crucial historical backdrop to many of his novels, including Weep Not, Child (1964) and A Grain of Wheat (1967).

Amongst those in the crowd was Gacheke Gachihi, who had travelled a far distance by bus as part of the youth delegation organising Ngũgĩ’s reception. Daniel arap Moi’s twenty-four-year dictatorship had ended two years earlier, marking an end of an era and the possibility of Ngũgĩ’s return.

Now the coordinator of the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Gachihi recalls the scene twenty-one years earlier when Ngũgĩ arrived. While government officials tried to quietly escort him away, he insisted on getting out of the car to touch the Kenyan soil. It was in that moment that Gachihi approached him, with his copy Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms (1993) in hand – Ngũgĩ’s collection of essays on the persistence of cultural imperialism.

‘Which book is this?’ Ngũgĩ asked him, before signing the book that transformed his thinking and helped propel him into political activism. This moment marked the first of several meetings between Gachihi, Ngũgĩ, and his family over the following two decades.

‘I remember one word from The River Between (1965) that stayed with me for twenty years – “bourgeoisie”’, Gachihi recalls as we discussed Ngũgĩ’s legacy the day after his passing on 28 May 2025, at the age of eighty-seven years. ‘It troubled me until I began studying class and class analysis’. Gachihi is amongst the generations of activists and revolutionaries who were politicised by Ngũgĩ’s writing, spanning six decades, as well as his own political work.

‘Unfortunately, much of his revolutionary legacy has been depoliticised’, he laments. ‘The mainstream – the educational system, the media, and even cultural institutions – focuses on his work in language and culture, ignoring his critique of neo-colonialism and class, and erasing the most radical aspects of his work’.

Left: Issue of Pambana (July 1983); Right: MWAKENYA’s Draft Minimum Programme (1987). Credit: Ukombozi Library.

He was referring to Ngũgĩ’s involvement in the December Twelve Movement (DTM), an underground Marxist-Leninist organisation active in the 1970s and 1980s. Named after the date of Kenya’s independence from British rule in 1963, the movement, also known as MWAKENYA, or Muungano wa Wazalendo wa Kukomboa Kenya (‘Union of Patriots for the Liberation of Kenya’), formed the foundations of Kenya’s radical left. In an interview with William Acworth in 1990, Ngũgĩ spoke about his role as the spokesperson in the midst of increasing oppression under Moi’s government, including the Wagaalla Massacre in 1984, which took the lives of over 1000 Kenyan Somalis. He cited some of the objectives of their Draft Minimum Program (1987): the recovery of national sovereignty, forming a democratic and patriotic culture, the pursuit of an independent foreign policy, and the establishment of a democratic political system. To him, the struggle for democracy was ‘not an abstract phenomenon’ but ‘becomes meaningful when it is linked to the struggle against neo colonial structure’.

Around the time of MWAKENYA’s founding, Ngũgĩ became active in the grassroots open-air Kamiriithu Theatre, as an instructor and collaborator, experimenting with performances in local African languages with local peasants and factory workers, building a space for education and cultural expression. It was there that he and fellow playwright Ngũgĩ wa Mirii staged the Gikuyu-language play Ngaahika Ndeenda (‘I Will Marry When I Want’) for six weeks. For their cultural and political work, on 31 December 1977, both writers were arrested and jailed without trial for the following year. The play, a sharp Marxist critique of post-colonial society, continued peasant dispossession and the effects of Christianity, was banned by the government based on ‘Public Security Regulations’.

Left: Cover of Ngaahika Ndeenda (‘I Will Marry When I Want’); Right: Kamiriithu Theatre, ca. 1970s.

Imprisonment in a maximum security prison, however, sharpened Ngũgĩ’s politics. He developed the ideas behind Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). In that seminal work, he introduced the concept of the ‘cultural bomb’ to describe violence of imperialism that ‘annihilate[s] a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, and in their capacities and ultimately in themselves’. Preserving and propagating African languages – ‘the collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history’ – was a deeply decolonial and political act.

In Ngũgĩ’s assessment of colonialism’s brutality, ‘The bullet was the means of the physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation’. So in prison, he decided to abandon English as his primary language of creative writing to embrace his mother tongue, writing his first novel in Gĩkũyũ on pieces of toilet paper. As he elaborates in Decolonising the Mind, writing in ‘a Kenyan language, an African language, is part and parcel of the anti-imperialist struggle of Kenyan and African peoples’. This act was also an attempt to bridge the class divide and make literature accessible to the very people, the peasants and the working class, whose struggles he sought to represent.

Ngũgĩ at a Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya protest in London, 1988. Credit: Ukombozi Library.

After leaving prison, Ngũgĩ was forced into exile in 1982, ending up in London, where he was supported by revolutionary comrades such as the Tanzanian Marxist Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu. There, Ngũgĩ took inspiration from South African anti-apartheid efforts and formed the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya (CRPPK). Publishing the Kenya News bulletin, the CRPPK was one of the most vocal groups to bear witness and broadcast the abuses of the Moi government.

While in exile, Ngũgĩ continued to write. In one of the most surreal and powerful examples of literary resistance, his 1986 novel Matigari ma Njiruungi (‘The Bullets of the Patriots’) about a freedom fighter Matigari gained widespread success in Kenya; it was read in bars, in buses, and in homes. So much so that rumours began to spread that this prophet-like figure was roaming though Central Province. In a climate of fear and repression, the Moi government even issued an order to arrest Matigari. Upon realising their embarrassment, police officers raided bookshops seizing every copy of the novel that they could find.

‘Ngũgĩ was arrested not for an act, but for a book’, says Gachihi, whose social justice centre runs a book club in Matigari’s honour. ‘The dictatorship thought they had detained a person. They feared the power of his words. That book became a key political text for educating the masses. His writing continued to build consciousness while in exile’.

Today, when reading the obituaries or homages to Ngũgĩ’s legacy, little is said of his political militancy from MWAKENYA to the CRPPK. ‘After decades of dictatorship and neoliberal rule, we still don’t have institutions to preserve and pass on these histories’, Gachihi laments. ‘Unlike in South Africa or Tanzania, where he is celebrated as a revolutionary intellectual, in Kenya he is seen more as a literary icon. He is like the prophet who is not honoured in his home’.

Ngũgĩ also warned against the dangers of the erasure of historical memory. In 2023, 60 years after Kenya achieved independence, Ngũgĩ published an article where he reflected on his political and creative work that pushed him into exile and the many ‘sacrifices that intellectuals, artists, and activists have had to endure to democratise our country’. He called on ‘our young patriots’ to study history – naming the Ukombozi Library, which generously provided materials for this art bulletin – particularly the archives of MWAKENYA and CRPPK. In that same article, he remembered the horrendous attack on him and his wife in his home shortly after returning from exile, saying, ‘Please don’t cry for me. Let us cry for our beloved country’. This Bulletin comes as thousands of Kenyans took to the streets across the country this week — 16 protesters were killed by the police — on the anniversary of the Finance Bill protests. The struggle for a more just Kenya continues. As we mourn Ngũgĩ passing and remember his life and work as a writer and political activist, we should take heed of these very words.

In Other News…

Exhibitions in Cuba and India.

For the 100-year anniversary of Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon, and Patrice Lumumba’s births, our friends at Utopix hosted a joint international poster exhibition, which includes work from our art department. The first was hosted at Casa de Las Américas, in Havana, Cuba, this month, alongside the III International Colloquium of the Afroamérica Study Program.

Last month, we also collaborated with Young Socialist Artists in India to host the ‘May We Rise’ exhibition, commemorating various revolutionary events and historical figures in the month of May, from May Day to Malcom X, from Ho Chi Minh to Rabindranath Tagore.

As part of our monthly portrait gallery, a collaboration between Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and Utopix, we pay homage to Malagantana Valente Ngwenya (1936–2011), one of Mozambique’s most celebrated painters and poets. Born this month, Malagantana, like Ngũgĩ, was a figure whose decolonial artistic genesis developed alongside his political involvement with FRELIMO (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), the liberation movement that overthrew Portuguese colonialism. This art bulletin is dedicated to Ngũgĩ, Malagantana, and the generations of militant artists whose life and work were dedicated to the unfinished struggle to liberate the African continent and the African people, with culture being one of the main theatres of struggle. As Ngũgĩ said, ‘The struggle for Africa’s soul is the struggle for its languages and cultures. It is the struggle for its memory. It is the struggle for its future’.

Warmly,

Tings Chak

Art Director, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

https://thetricontinental.org/triconart ... wathiongo/

******

Seven killed in Togo protests against President Gnassingbé’s rule

Protests erupted last week in Togo as citizens demanded President Gnassingbé’s resignation, following a constitutional change that could allow him to extend his more than 20 years in power.

July 02, 2025 by Nicholas Mwangi

Protests in Lomé against President Gnassingbé’s rule. Photo: screenshot

Over the past week, thousands of Togolese have flooded the streets of Lomé, the capital, and other cities, demanding the resignation of President Faure Gnassingbé and denouncing constitutional changes that will entrench his decades of dynastic rule. The demonstrations, which began on June 26, have been met with heavy police repression, resulting in at least seven reported deaths and numerous injuries. The protests were organized by activists on social media platforms and youth-led civic movements.

A dynasty extended: 58 years of Gnassingbé rule

The protests are the latest in Togo’s long-running struggle over democracy and succession. Faure Gnassingbé has ruled since 2005, when he succeeded his father, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who seized power in 1967 and remained president for 38 years until his death. Combined, the Gnassingbé family has governed Togo for 58 years, a fact that has fueled widespread frustration among ordinary citizens and civil society groups.

Controversial constitutional amendments

Tensions have been building since the National Assembly in April 2024 passed a new constitution that fundamentally restructures the country’s political system. Under the reforms:

A parliamentary system is established, replacing the direct popular vote for presidential elections.

The head of government will now be the president of the Council of Ministers (PCM) – a newly created position wielding full executive, civil, and military authority.

The PCM will be elected by the National Assembly rather than by the public.

The PCM’s term is set at six years and can be renewed indefinitely.

Presidential terms are extended from five to six years and capped at a single term, but Gnassingbé’s nearly two decades already in office will not count toward this limit.

The changes were adopted by a parliament dominated by the ruling Union pour la République (UNIR) party, which secured majority seats in legislative elections held shortly after the constitutional revision.

And in May 2025, Faure Gnassingbé was formally sworn in as Togo’s first president of the Council of Ministers, cementing his control over all levers of government. The post, effectively a super-prime ministership, carries more power than the presidency itself. As analysts argue it was designed specifically to allow Gnassingbé to remain in power indefinitely while technically complying with term-limit provisions.

Growing public outrage

The recent wave of protests was sparked by this perceived democratic backsliding. Demonstrators are calling for the president’s resignation and also protesting the high-cost of living.

However, police responded to the demonstrations with tear gas, batons, and, in some cases, live ammunition. Human rights organizations have documented at least seven fatalities and dozens of injuries. Authorities have not provided an official death toll.

The current demonstrations are similar to a major wave of protests in 2017-2018, when tens of thousands of Togolese took to the streets demanding an end to the Gnassingbé dynasty and a return to a two-term presidential limit. Even back then, there were accusations of the government systematically dismantling democratic safeguards to prolong the family’s rule.

Togo has also long struggled with contested elections, repression of dissent, and calls for democratic reform. With the new constitutional framework, the path forward remains uncertain against decades of entrenched power.

https://peoplesdispatch.org/2025/07/02/ ... gbes-rule/

*****

Aggressors Unnamed in Rwanda-DRC “Peace Agreement”

Ann Garrison, BAR Contributing Editor 02 Jul 2025

Rwandan and M23 forces are the aggressors in DRC. They are integrated under Rwandan command.

The foreign ministers of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo sat down with Secretary of State Marco Rubio to sign a so-called peace agreement at the US State Department on Friday, June 27, but the agreement does not even name the aggressors, Rwanda and its M23 militia, as such. It echoes the 2013 Geneva conference where Congolese activist Bénédicte Njoko was thrown out after confronting then Secretary Ban Ki-Moon for “guaranteeing” peace without naming the aggressors. The more things change, the more they remain the same for the Congolese, who have no powerful friends.

Despite stating that the two countries will respect one another’s territorial integrity, the agreement does not say that Rwandan troops must immediately withdraw from DRC or even acknowledge that they are aggressors there, and it does not say that there are no Congolese troops in Rwanda.

M23 operates under Rwandan command

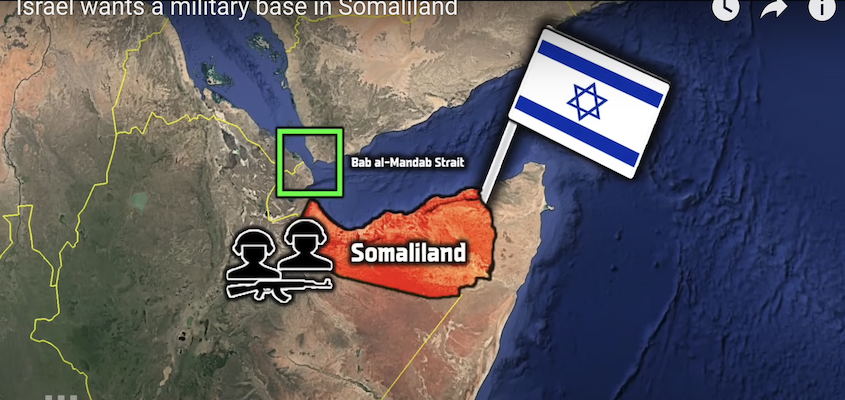

In June and December 2024, UN investigators reported that thousands of Rwandan troops were in DRC, outnumbering those of the M23 militia, and that Rwandan and M23 militia troops were integrated under Rwandan command.

In M23/Rwanda’s military offensive launched last January, they seized the capitals of both North and South Kivu Provinces and appointed their own governors, effectively putting Rwanda in control. The agreement does not say that M23—again, operating under Rwandan command—will surrender its control of the two provinces, which Rwanda has long looked to annex.

Despite all the evidence that M23 operates with Rwandan troops under Rwandan command, the agreement refers to it as distinct from the Rwandan army. It says that M23 and DRC are negotiating their own agreement in Doha, as though M23 were simply Congolese “rebels,” as they have long claimed.

From Goma, the capital of North Kivu, Al Jazeera’s Alain Uaykani reported that fighting continued, even as the peace agreement was being signed, and that Congolese are concerned because it says nothing about M23’s withdrawal from the Kivu Provinces.

“You heard clearly that they are not mentioning the M23 rebels and AFC coalition,” he said. “They are now in control of the big province, like in North Kivu here, and also South Kivu. They have been appointing governors.”

Total capitulation to Rwanda’s narrative

The agreement makes only three references to M23, one in the glossary. The other two simply say that the parties will respect ongoing negotiations between M23 and DRC.

It makes 43 references to the FDLR , the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, a militia of Rwandan refugees and children of refugees who fled into eastern DRC at the end of the Rwandan war and genocide in 1994.

For decades President Paul Kagame and other Rwandan officials have repeated that the FDLR threaten to return to repeat the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and that they are the source of all the instability in Congo and the region. Rwandan Foreign Minister Olivier Nduhungirehe repeated Rwanda’s mantra at the State Department press conference before signing the agreement with a smug grin.

“This is grounded in the commitment made here for an irreversible and verifiable end to state support for FDLR and associated militias that is the bedrock of peace and security in our region,” he said. Jeune Afrique later quoted him saying that Rwandan troop withdrawal is contingent on neutralization of the FDLR. In other words, Rwandan forces can stay as long as they want just by claiming that the FDLR is still fighting.

This Rwandan narrative flies in the face of 30 years of well-documented Rwandan aggression. Rwanda invaded DRC with Uganda in 1996 and then again in 1998. According to the 2010 UN Mapping Report , its army killed tens of thousands of Hutu refugees in crimes that a competent court might rule to be genocide, war crimes, and/or crimes against humanity. Thirty years of UN investigations have also documented Rwanda’s theft of vast quantities of Congolese minerals and other resources. The agreement makes no mention of these crimes and doesn’t even acknowledge the presence of Rwandan troops in the country except in oblique reference to Rwanda’s “defensive measures.”

The so-called peace agreement’s representation of Rwanda’s actions as “defensive” and its singular focus on the FDLR as a source of instability represent a complete capitulation to Rwanda’s narrative.

Something else the agreement does not say is that Congo’s vast resources belong to the Congolese people. It refers to regional integration and lawful process in vague terms and says that both parties will benefit from “regional critical mineral supply chains.” This is widely understood to mean, for one, that Rwanda will become the region’s minerals refining hub, even though its mineral reserves pale by comparison to DRC’s.

Trump says he’s out of his depth but celebrates minerals haul

President Trump told reporters that he was out of his depth regarding the Congo conflict but that his advisor on the Congo, Massad Boulos, is not, and that the US will gain a lot of Congolese mineral rights from the deal.

“I'm a little out of my league in that one because I didn't know too much about it. I knew one thing, they were going at it for many years, with machetes, and it is one of the worst, one of the worst wars that anyone's ever seen. And I just happened to have somebody that was able to get it settled.

“I mean, just a brilliant person who is very comfortable in that part of the world. It's a very dangerous part of the world. I said, ‘Are you uncomfortable there? People are being killed. School children are being raided and killed. And I don't even want to say how, but as viciously as I've ever heard. Are you uncomfortable?’

“‘No,’ [he said], ‘that's the part of the world that I know. Very comfortable.’

“He was able to get them together and settle it, and not only that, we're getting for the United States a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo.”

Trump did not say that the Congolese people will benefit, as they most surely will not. Despite Congo’s vast resource wealth, it is the fourth poorest country in the world.

https://blackagendareport.com/aggressor ... -agreement

Donald Trump’s Congo Venture: A Scramble for Minerals Under the Guise of Peace

Maurice Carney 02 Jul 2025

Trump’s ‘peace deal’ between Rwanda and the DRC is a corporate resource grab disguised as diplomacy, rewarding Rwandan war crimes while U.S. investors stake claims to Congo’s coltan mines.

The Trump Administration brokered a vaunted peace agreement between the Republic of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) on June 27, 2025. The Agreement was witnessed by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and signed by Rwandan Foreign Minister, Olivier Nduhungirehe and DRC Foreign Minister, Therese Kayikamba-Wagner. The Agreement is a codification of the Declaration of Principles that the two foreign ministers signed on April 25th under the aegis of Marco Rubio at the State Department. The Signing of the Agreement on June 27th was followed up on the same day with a White House ceremony and briefing that included the two foreign ministers, Secretary Rubio, Vice-President JD Vance, and Trump's Senior Advisor for Africa, Massad Boulos. The Ceremony was cringe worthy but appropriate for the representatives of two of the three leading neo-colonial regimes in the Great Lakes region of Africa - Uganda is the third of the three. Donald Trump was not far off the mark when he stated that the foreign ministers must be really happy to be in the White House. A White House visit with the President of the United States is a feather in the cap for neo-colonial leaders in Africa; in essence a key marker of legitimacy.

During the White House ceremony, Donald Trump declared "We are here today to celebrate a glorious triumph." The Agreement is anything but a glorious triumph by the way. He went on, "today the violence and destruction come to an end and the entire region begins a new chapter of hope, opportunity, harmony, prosperity, and peace." The twisted White Savior vision is of a Donald Trump coming to save the day between two savage African nations killing their citizens with machetes. But that vision flies in the face of the reality of the United States’ 65-years of destructive foreign policy in the Congo. From the mounting of the CIA's largest covert action in the world at the time in the 1960s to overthrow Congo's democratically elected Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, to the installation and maintenance of the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko for over three decades and the wholesale backing of successive invasions by Rwanda and Uganda that triggered the greatest loss of life in any conflict in the world since World War II,, the United States is in large part responsible for the current devastation that we see in the heart of the African continent.

Should one accept Donald Trump's narrative, US citizens would never know that the United States was the major foreign force responsible for trapping the Congolese masses in perpetual wars, instability, and abject poverty. Trump’s narrative is co-signed by Congo's neo-colonial leader Felix Tshisekedi who like all Congolese heads of state since the US overthrow of Lumumba ascended to power due to the sign-off of the United States even though he was not the rightful winner of the elections. Felix Tshisekedi said "If President Trump can mediate and put an end to this war, he deserves the Nobel Prize. I would be the first to vote for him."

The Peace Agreement or what is to be called the "Washington Accord" is very unlikely to bring an end to the conflict in the Congo. The agreement is framed as if Rwanda and the DRC were two nations at war on each other’s territory, when in fact the conflict is a three-decade long war of aggression, plunder and occupation spearheaded by Rwanda and Uganda and backed by the United States and other Western powers. It is a war that has played out on Congolese soil and on the backs and bellies of Congolese women. There was even a six-day war in 2000 when Rwandan and Ugandan militaries fought each other inside the Congo in the city of Kisangani. The victims have been Congolese. An estimated six-million Congolese have perished due to the on-going war and hundreds of thousands of Congolese women have been systematically raped and sexually terrorized. It is the deadliest conflict in the world since World War IITwo. It is a war of aggression, plunder and occupation that has been able to persist because of Western nations arming, financing, training, equipping and providing diplomatic and political cover to Paul Kagame and the Rwandan government for three decades.

This year alone, seven thousand Congolese have perished due to Rwandan military capture and occupation of Goma, a city of two million inhabitants bordering Rwanda in the east of the Congo. An estimated seven million Congolese are internally displaced due to Rwanda's war in the Congo and its command and control of the militia group named M23. They currently occupy and control the North and South Kivu provinces in the east of the DRC. The United Nations Security Council in a unanimous 15 to 0 vote on February 21st passed resolution 2773 which called on "the Rwanda Defence Forces to cease support to the M23 and immediately withdraw from DRC territory without preconditions." The peace Agreement, which has nine provisions, seven of which are substantive and two which are perfunctory does not make the explicit call for Rwandan soldiers to withdraw from the Congo and cease its support of the M23. The agreement cosigns Rwanda's Orwellian propaganda about Rwanda relaxing "defensive measures." The notion of "defensive measures" is not fundamentally different from Israel claiming to defend itself while carrying out a genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza. The illogic is that Rwanda must occupy the Congo, particularly its critical minerals mines in order to defend itself from a spent group called the Democratic Forces For The Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR in French). Some of its members were involved in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Rwanda has used them as a casus belli for massive atrocities and resource theft in the Congo.

In addition to the peace agreement not calling for the immediate unconditional withdrawal of Rwanda soldiers as was voted at the UN Security Council, there are many other major shortcomings that do not bode well for peace in the Congo:

1. It prioritizes going after the FDLR who represent more of a threat to Congolese civilians than they do to Rwanda

2. It does not address at all the M23 which is the militia group controlled and commanded by Rwanda and currently occupies two provinces in the east of Congo. Apparently, Qatar is supposed to advance a separate peace Agreement between M23 and the Congolese government.

3. There is no punishment or accountability on the part of Rwanda for its crimes in the Congo, which means no justice for the Congolese victims of Rwanda's war crimes and crimes against humanity

4. It offers Rwanda legal access to Congo's minerals, which it has been plundering illicitly for three decades

5. It proposes a tried and failed process of integrating militia groups into the Congolese military to offer incentives for putting down the guns.

The agreement benefits the local and global elites at the expense of the Congolese masses. Paul Kagame and the Rwandan leadership are not held to account for the crimes they have committed in the DRC. In fact, they are rewarded with promises of US investments and access to Congo's riches through the regional economic integration framework of the agreement. Donald Trump explains best how he and the United States benefit. He stated that, "We are getting a lot of the mineral rights for the United States from the Congo." One of Trump’s wealthy friends, a Texan tycoon named Gentry Beach, Chairman of America First Global, has claims on the Rubaya Coltan mine that was captured by Rwanda and the M23. It is the largest coltan mine in the world and accounts for about 15% of coltan produced globally. The final beneficiary is Felix Tshisekedi himself and the comprador class in Kinshasa who get to stay in power. The US intervention to halt the military offensive of the M23 benefited the corrupt Kinshasa class even though the Trump administration's aim was to enable the majority owned U.S. company Alphamin to restart its tin mining operations that had been captured by the Rwandans and their M23 militia.

It is the Congolese masses in particular and Africa in general who lose out among the local and global elites. Congolese do not stand to get either justice or peace. In addition, they will almost certainly not benefit from the wealth beneath their feet as US investors and the billionaire class descend on the Congo like vultures picking apart a carcass. This does not bode well for the advancement of the African continent writ large. If the Congo is captured by U.S. capitalists, it will be a big hole in the heart of the African continent and serve as a major obstacle for the revolutionary Pan African sovereignty movements unfolding on the Continent. Frantz Fanon's words ring even louder today than it did decades ago when he declared, "The fate of all of us is at stake in the Congo."

https://blackagendareport.com/donald-tr ... uise-peace