This file photograph shows Thomas Sankara as he reviews troops in a street of Ouagadougou, during celebrations of the second anniversary of the Burkina Faso’s revolution. Photo by Daniel Lane/AP.

Thomas Sankara remains a global icon

By Owen Schalk (Posted May 17, 2024)

Originally published: Canadian Dimension on October 9, 2024 (more by Canadian Dimension) |

“We encourage aid that aids us in doing away with aid,” asserted Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987.

But in general welfare and aid policies have only ended up disorganizing us, thus beguiling us and robbing us of a sense of responsibility for our own economic, political and cultural affairs.

In order to restore that sense of responsibility, Sankara implemented a socialist, anti-imperialist agenda aimed at cultivating a self-sufficient economy run by the Burkinabè people, for the Burkinabè people. His agenda included, among other things, refusal to pay Burkina Faso’s debts to Western-run institutions on the grounds that, one, it was illegitimately accrued, and two, constant debt serving was anathema to African development.

As ideologically void military coups rock Burkina Faso and the debt crisis across the African continent grows more urgent by the year, the Burkinabè people are readying to commemorate Sankara on the thirty-fifth anniversary of his assassination. Sankara’s four years in power proved that alternative development models that do not subscribe to the imported precepts of neocolonial institutions are not only possible, but necessary if underdeveloped nations want to develop in endogenous and sustainable ways.

When Sankara seized power in 1983, his government represented a radical break from the past. Named “Upper Volta” by the French and underdeveloped in a classic colonial fashion, formal independence brought little material change to the country. A series of puppet rulers kept the country in France’s neocolonial dominion, while the majority of Upper Volta’s population remained undereducated and undernourished. When Sankara, a military captain who espoused the tenets of Marxism-Leninism, took power in a coup, continent-wide hopes for African socialism were reinvigorated. The Zanzibarian socialist A.M. Babu summed up the hopeful feeling:

Captain Thomas Sankara… can be instrumental in reviving that post-colonial enthusiasm which most people had hoped would be rekindled by [Mugabe’s] Zimbabwe but was not; the enthusiasm that cleared bushes, built thousands of miles of modern roads, that dug canals on the basis of free labour and the spirit of nation-building.

A man of informal style and modest values, Sankara nevertheless espoused an ambitious development program for the African continent. Firstly, he renamed his country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso—“the land of upright people”—and nationalized the majority of its resources, most importantly the farmland and mineral reserves. He launched a series of “commando” operations to build a nation-spanning railroad (the people constructed almost 100 kilometres of railway in two years), increase literacy in the countryside (tens of thousands were taught to read), and vaccinate children against measles, meningitis, and yellow fever (two million children were vaccinated in two weeks, saving 18,000 to 50,000 kids who usually died in the yearly epidemics). All these initiatives were undertaken without accepting funds from international financial institutions or encouraging foreign investment.

“We don’t want anything from anyone,” said Foreign Minister Basile Guissou. “No one will come to develop Burkina Faso in place of its own people.” At a time when Africa’s debt was around $200 billion and 40 percent of the continent’s export earnings were going toward debt payments, this was a brave stance to take. Sankara went one step further when, in 1987, he urged the rest of Africa to reject its foreign debt and follow Burkina Faso’s successful model of self-sufficiency.

Sankara’s goal was to ensure the population’s access to food and clean drinking water, a basic but demanding ambition on a continent where hunger and thirst were enforced on whole peoples through the financial institutions and foreign policy agendas of the “civilized” Western world. “Our economic ambition,” he said,

is to use the strength of the people of Burkina Faso to provide, for all, two meals a day and drinking water.

His policies bore fruit. Between 1983 and 1986, cereal production rose 75 percent and the new Ministry of Water helped many communities dig wells and water reservoirs. Journalist Ernest Harsch recalls:

Ordinary Burkinabè seemed to readily embrace Sankara’s approach, as they mobilized in their local communities to quickly build new schools, health clinics, and other facilities that had once seemed but a remote fantasy.

Sankara’s independent development policies, combined with a non-aligned foreign policy that saw him enjoy good relations with Cuba, Libya, and the Soviet Union, led the Europeans (and particularly the French) to turn against the revolutionary government. Much like other revolutionary processes in Cuba and Venezuela, Sankara’s government was successfully implementing a new development strategy that spurned the racist paternalism and interventionist austerity of Western financial institutions in favour of a model of self-sufficiency rooted in popular mobilization. Moreover, Sankara demanded respect from the Global North, and especially from Burkina Faso’s former colonizer. “What is essential,” he stated,

is to develop a relationship of equals, mutually beneficial, without paternalism on one side or an inferiority complex on the other.

The French government’s attitude toward Sankara grew increasingly negative during his time in power. For example, during a brief border war between Mali and Burkina Faso in 1985, France sold weapons to Mali. Overall, Sankara had deprived France of influence in West Africa, and the success of his alternative path portended an even greater diminishment of French influence as other peoples in the region would likely realize that self-sufficiency was possible. As such, the French retained close ties with conservative governments in neighbouring Togo and Côte d’Ivoire, especially the Ivorian president Félix Houphouët-Boigny, whose country was home to many Burkinabè exiles who opposed the Burkinabè revolution.

When Sankara traveled to Côte d’Ivoire in May 1984, he was initially banned from visiting Abidjan, the largest city, because Ivorian authorities were worried he would be welcomed more enthusiastically than the country’s own president.

Everything fell apart on October 15, 1987, when former Sankara compatriot Blaise Compaoré launched a coup of his own. His soldiers murdered Sankara and his closest allies and unceremoniously buried their bodies in a mass grave. Harsch reported that, when word of Sankara’s death spread, mourners flocked to the mound to lay flowers and weep.

Compaoré ruled until 2014. Some of his earliest actions included reversing the state monopoly on the mining industry and allowing the International Monetary Fund and the World to return to the country. “Without shame, we must appeal to private investors,” he announced in a clear break from Sankara.

We need to develop capitalism… We have never considered socialism.

In further contrast to his predecessor, Compaoré built an opulent presidential palace and purchased a luxury jet once owned by Michael Jackson. The West’s immediate embrace of Compaoré and the new leader’s closeness to France (and particularly French ally Félix Houphouët-Boigny) have fed theories that the coup was launched at the behest of Burkina Faso’s former colonizer. To this day, the French government refuses to open its archives on Sankara.

By the late 1990s, foreign exploration teams had discovered huge gold reserves in Burkina Faso. Canada, with its growing investments in gold, was especially interested. By 2003, the following Canadian companies were exploring or developing mines in Burkina Faso: Axmin, Orezone Resources, Etruscan Resources, St. Jude Resources, SEMAFO, and High River Gold. Within fewer than twenty years, Canadian interests would own the majority of gold operations in the country, dominating Burkina Faso’s most profitable export.

In 2014, a popular uprising overthrew Compaoré, bringing an end to decades of openly neocolonial rule. However, the political process that followed failed to break with the past as Sankara would have advised. Canadian pressure was instrumental in preventing substantial reform. As Business Monitor Online explained, “Burkina Faso is heavily dependent on foreign aid, much of it from Canada, the home jurisdiction of most of the miners that would be hurt by significant review.” Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper further protected Canadian investments by finalizing a Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA), negotiated with the Compaoré regime, while the unelected transition government was in power.

A 2015 meeting between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and former President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré revealed the continuing prevalence of Canadian capital in the country today. As Canadian mining investments in Burkina Faso and all West Africa continued to rise, Kaboré shook hands with Trudeau and “underscored the importance of Canadian investments to Burkina Faso’s economy.”

This year, Burkina Faso has been the site of two military coups. The first, on January 24, overthrew Kaboré and brought officer Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba to power, and the second, on September 30, dislodged Damiba and elevated officer Ibrahim Traore to the head of the military regime. Neither of these coups impacted Canadian investment in the country. An October 3 article in Canadian Mining Journal notes that operations owned by Canada’s Endeavor Mining and IAMGOLD “have not been affected by spreading social unrest following an internal coup d’état.”

Sankara’s vision of an independent, socialist, pan-Africanist model of development—one in which wealth produced in Africa remains in Africa to develop the majority of the population—was not buried with him. He remains an inspiring symbol for people in Africa and beyond. In a recent interview with Democracy Now!, Aziz Fall, coordinator for the International Campaign Justice for Sankara, explained that Sankara “symbolized for most African youths the hope of a sovereign Africa. He actually gave his life for that… And so he’s an icon, I think."

https://mronline.org/2024/05/17/thomas- ... obal-icon/

******

Sudan: Revolutionary Movement Plots the Path to Peace

Posted by INTERNATIONALIST 360° on MAY 17, 2024

Mohammed Amin

A street in the city of Omdurman damaged in the year-long war in Sudan, May 2024 (Reuters)

As fighting between the RSF and army rages on and the situation in Darfur worsens, Sudan’s resistance committees have difficult choices to make.

Early in April, leaders of Sudan’s radical revolutionary group Anger Without Borders met with Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the country’s de facto ruler.

Members of the group had been fighting alongside the army in its war against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has been ongoing since 15 April last year, claiming the lives of tens of thousands of people and displacing over eight million Sudanese from their homes.

But while Anger Without Borders had taken up arms alongside the army, its meeting with Burhan started an argument on social media. Burhan, after all, was the man who, along with Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the RSF chief better known as Hemeti, had orchestrated the military coup of October 2021 that blew up Sudan’s transition to full civilian leadership.

And so, Anger Without Borders was accused of seeking to legitimise military rule in Sudan through its meeting with Burhan who, over the Eid al-Fitr holiday of 10 April had announced that his aim was not to return the country to any kind of civilian government.

Appearances, though, can be deceptive. What really happened, according to group member Nuha Abdul Gadir, who spoke to Middle East Eye, was an ambush. The revolutionaries had been set up as part of a “piece of propaganda”.

“The members of Anger Without Borders were summoned for a normal meeting, then suddenly found themselves in a room with Burhan. Our leaders tried to leave but the soldiers prevented them. They were lured there so Burhan could be photographed with them,” Gadir told Middle East Eye.

‘We can’t put our hands on the hands of Burhan, which have been dirtied by the blood of the revolutionaries’

– Nuha Abdul Gadir, Anger Without Borders

“We can’t put our hands on the hands of Burhan, which have been dirtied by the blood of the revolutionaries. Our leaders joined the army to defend our people from the violations of the RSF,” she said, specifying that fighting the RSF was not the same as fighting for the army, and referring particularly to the army and RSF-led operations against protesters in 2019, which left hundreds of civilians dead.

With Sudan’s war now more than a year old, the country’s revolutionary movement, as well as its technocratic civilian leaders, has been trying to forge a pathway to peace that does not end up solidifying military rule.

Sometimes, this has meant taking difficult decisions, with different civilian actors seeming to offer support to one or other of the warring parties. The army is now made up of a constellation of different groups representing wildly diverging ideologies, from radical revolutionaries to ultra-conservative Islamists.

Many of those groups see the army as a means to an end: namely, defeating the RSF, which international human rights groups have concluded is committing genocide against “non-Arab groups” in Darfur, the vast western region of Sudan that serves as its powerbase.

Heart of the revolution

The resistance committees – nationwide groups of local activists that have been at the heart of Sudan’s revolutionary movement – have, along with the affiliated emergency response rooms (ERR), been organising lifesaving wartime support across Sudan, and are actively trying to bring the war to an end.

In a document titled, “The political vision to end the war in Sudan,” the resistance committees have detailed their bottom-up approach to solving the crisis in Sudan through political pressure and popular organising. This stands in contrast to the approach taken by technocratic civilian actors like former prime minister Abdalla Hamdok’s Taggadum coalition, which is seeking to convince the warring parties to head back to the negotiation table.

The next round of US- and Saudi-mediated ceasefire talks, scheduled to being in Jeddah, are now no longer happening.

At a recent conference in Paris, the international community pledged $2bn in aid for Sudan. Neither the SAF nor the RSF was invited to take part in the conference, which was attended by Sudanese civilian actors.

The resistance committees have expressed doubts over the commitment of international donors and hit out at world actors for “forgetting” the crisis in Sudan.

A leading resistance committee member from Gezira state told MEE that the groups’ roadmap called for the dismantling of the RSF and the creation of a new army that would stay out of Sudan’s politics and allow the building of full civil rule.

The source, who asked for anonymity for security reasons, said this would not be possible under the SAF’s current leadership, which is against the revolution and against civilian rule.

“The question of how to build a new army is the main challenge for the war in Sudan. We are working with retired officers and officers who have been dismissed to formulate the creation of a professional army that accords with the process of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration,” he said.

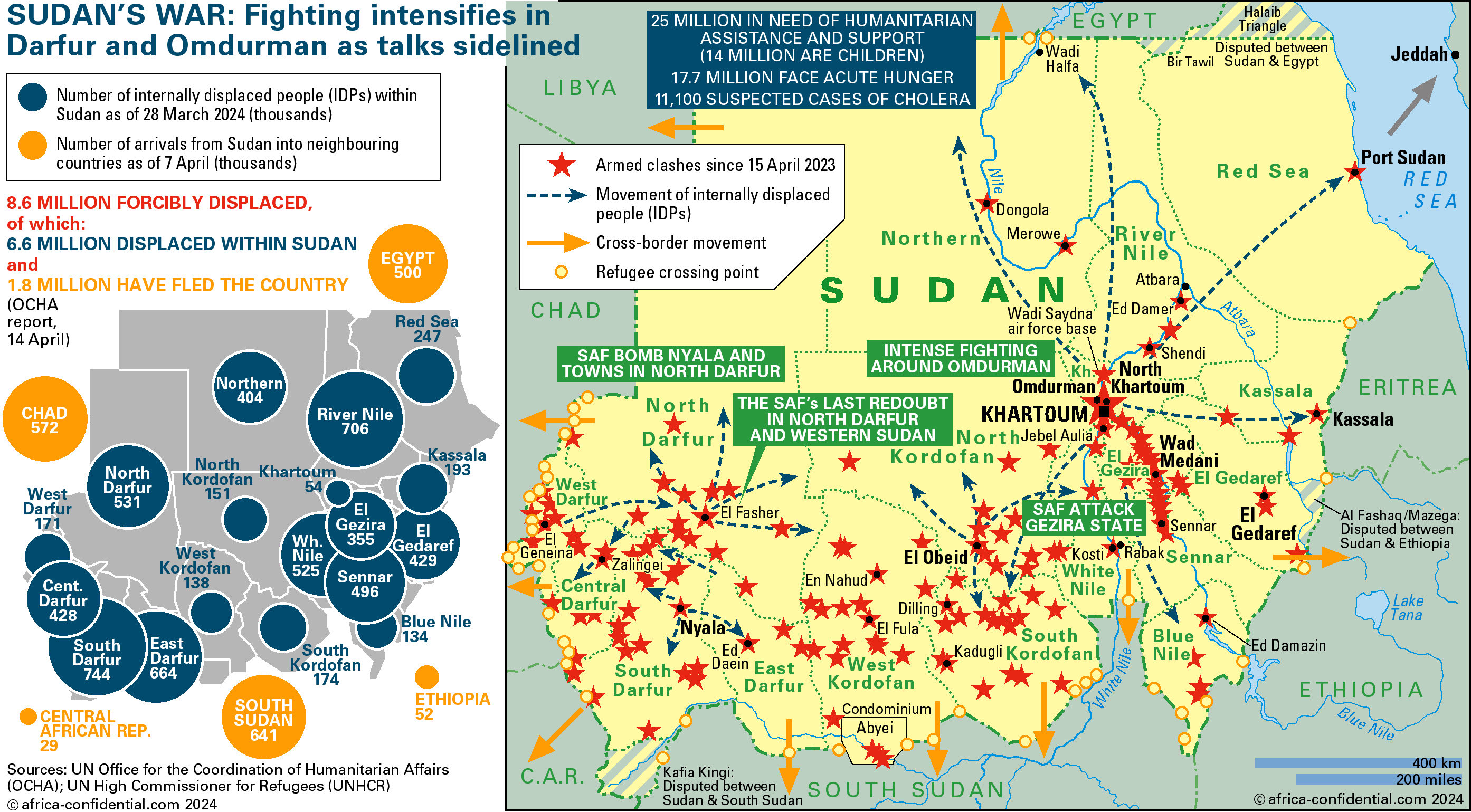

Sudan updateAfrica Confidential’s Sudan situation update (Courtesy of Africa Confidential)

The resistance committee leader said they were against the RSF “and against the leaders of the SAF who failed to protect the people. We also warn the elites that are supporting the militias and foreign countries that are supporting the militias to stop what they are doing”.

The United Arab Emirates is the RSF’s main patron, while Africa Confidential has reported that the army has been operating Iran-supplied drones, notably the Mohajer-4 and Mohajer-6, since January.

Middle East Eye recently reported on Russia’s role in the war, as Moscow moves to play both sides, strengthening relations with the army while continuing to facilitate the supply of the RSF through the Wagner Group.

“Our roadmap also includes the formation of revolutionary governments from the grassroots in different states after the design of new interim constitutions through a dialogue between the Sudanese people,” the resistance committee source said.

‘Impossible balance’

Muzan Alneel, a Sudanese scholar, described the resistance committees as the only genuine democratic group to face the militarisation of politics in Sudan.

“The success of the resistance front in advancing its position was captured in the slogan of the ‘Three Nos’ – no negotiations, no partnership, no legitimisation – against the military council,” Alneel, co-founder of the Innovation, Science and Technology Think-tank for People Centered Development, told MEE.

‘We believe that junior army officers, who have no interest in continuing the war, will stand with our vision’

– Resistance committee leader

In the period leading up to the beginning of the war in April 2023, this slogan was chanted at protests and, Alneel said, even the civilian Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, made up mostly of technocratic, elite politicians, “felt compelled to include it at the bottom of their statements”.

However, the argument the resistance committees made – that “the latest coup would only encourage further violence and perhaps even a war” was, Alneel said, ignored by international political and media organisations.

“For the two warring entities – both of which had expanded their influence using violence, massacres, and coups, and faced no consequences other than further legitimisation – it was only logical to attempt a full takeover via further violence,” Alneel told MEE.

But she criticised the resistance committees for now supporting the army to protect the state, saying they had “attempted to strike an impossible balance between calling for an end to the war and supporting the army of the coup government”.

“For months, they attempted to hold together two contradictory goals: namely, the revolution’s goal of protecting and prioritising human life, and the counter-revolution’s goal of protecting the state,” Alneel said.

“The counter-revolution, boosted by decades of bourgeois propaganda promoting patriotism over human life, appears to have defeated the revolution,” she said.

Situation on the ground

Facing little real pressure from the outside world, both sides have escalated the fighting, with the army targeting Khartoum and Gezira states.

There is fierce fighting in el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, where there are fears that the RSF could massacre non-Arab civilians. Across Darfur, there is already “clear and convincing” evidence that the RSF is committing genocide.

Currently, according to a military analyst monitoring the battle, the RSF is maintaining static positions around el-Fasher, with clashes and exchanges of artillery taking place in the northern and eastern sectors of the city.

Sudan update ACAfrica Confidential’s Sudan battlefield update (Courtesy of Africa Confidential)

Former rebel movements from Darfur and Blue Nile are fighting alongside the army and they have shifted the balance of power slightly, advancing towards Gezira state, which has been under RSF control since the paramilitary stormed through it in December, meeting little army resistance.

The army is laying siege to the RSF-controlled al-Jili oil refinery north of Khartoum, alongside rebel fighters from Darfur governor Minni Minnawi’s Sudan Liberation Movement.

“The pro-SAF Darfur rebels are fighting hard in al-Jili and Gezira but not really making advances. There are serious coordination issues between the SAF and rebel groups,” the military analyst said.

“We are besieging the RSF in al-Jili around the Khartoum oil refinery and we believe that its seizure is only a matter of time for us. We have destroyed 37 vehicles and captured 18 others from RSF,” Alsadig Alnur, a spokesperson for the SLM/ Minnawi faction, told MEE earlier this month.

The former rebels of another faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, led by the deputy head of the Sovereign Council, Malik Agar, are advancing from Sennar state towards RSF-controlled areas in the south of Gezira state. Eyewitnesses told MEE there had been fierce fighting in Wad Alabas, eastern Gezira.

The war has devastated Sudan. According to the UN, almost 25 million people will be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2024, while 8.8 million have been displaced from their homes.

Mass killing, rape and sexual assault, theft and looting have all been widespread, as the Sudanese people struggle to see an end to the bloodshed.

https://libya360.wordpress.com/2024/05/ ... -to-peace/