Digitalisation in India: The class agenda [Part IV]

Originally published: RUPE (Research Unit for Political Economy) India on May 23, 2024 by RUPE India (more by RUPE (Research Unit for Political Economy) India) (Posted May 28, 2024)

Examining India’s digital sector in relation to the world economy, we observe the following: (1) the international division of labour in the digital economy, whereby cheap labour power in India is used to raise the rate of profit of imperialist countries’ firms; (2) the domination of India’s market for digital goods and services by firms of the imperialist countries; (3) the capture and control of data, as a raw material, by these firms; (4) the use of foreign investment to capture economic territory in India; and (5) the use of political influence by U.S. imperialism to shut out rivals.

Part IV. Imperialism and the Digitalisation of India

The digital production process

Indian propagandists talk of India’s “emerging status as a technological powerhouse”, and the heads of the world’s largest technology corporations have started to refer to India as a global technology/software “superpower”, at least in their interactions with Indian media outlets.1 Undeniably, India has a large pool of technologically skilled workers (albeit small as a percentage of the country’s workforce) as well as globally competitive firms in specific sectors of software and related technology. But India’s technology sector is not a ‘superpower’, or even an emerging one. It does not disturb, let alone upturn, the existing hierarchy of world powers, even in the sphere of the digital economy. Rather, India plays an important but subordinate role in the international division of labour under imperialism.

That division of labour, as Christian Fuchs describes it,2 includes the contingent of workers who mine the minerals required for the digital sector; these minerals are then processed by various other contingents of workers, over many stages, into physical components of information and communication technology (ICT); another contingent of workers assembles these components into various finished physical goods. These stages generally span many countries, from, say, the Congo to China or Vietnam.

These physical goods are then used by workers in non-material production (among whom there is a hierarchy of tasks involved) to construct information technology. In turn, the products of their labour are used by other workers to create digital content of various types. Fuchs notes: “Today most of these digital relations of production are shaped by wage labor, slave labor, unpaid labor, precarious labor, and freelance labor, making the international division of digital labor a vast and complex network of interconnected, global processes of exploitation.” To take just one example, an army of ‘invisible’ workers around the world is employed in training artificial intelligence systems by identifying, say, a tree on a video, or correcting a translation. Amazon, Google, and other tech giants run on vast amounts of such ‘ghost work’, by workers paid less than minimum wages, without health benefits, and with no job security.3 Facebook is reported to engage at least 100,000 ‘content moderators’, and perhaps many more than that, “spread across a range of call centers, boutique firms, and ‘micro-labor’ sites around the world”,4 and similar is the case for other social media sites.

The surpluses extracted at each stage of this vast, multi-layered production process are concentrated in the hands of giant corporations which control each step. At least 6 of the world’s 10 richest persons (from the Forbes list of 2024) made their fortunes in the tech sector (Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Ellison, Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, Larry Page).5 Worldwide, the six largest public corporations by market capitalisation are Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, and Meta (Facebook), with a combined market capitalisation of $7.3 trillion as of March 31, 2024.6

Indian IT workers in the international division of labour

Workers in India’s tech sector are located within this global division of labour. Giant multinational corporations employ them in order to reduce their own wage costs and increase their profits. Thus India’s software services exports rose from $3 billion in 1999-2000 to $100 billion in 2016-17 to almost $200 billion in 2023-24.7 Software exports are the major part of services exports, which are estimated at $340 billion for the calendar year 2023.

Value of Export of Software Services from India, by Country of Destination

| Report on Services Export Reporting Form for 2022 23 Ministry of Commerce | MR Online

Report on Services Export Reporting Form for 2022-23, Ministry of Commerce.

Another, and increasingly important, part of India’s services exports is that of ‘global capability centres’ (GCCs) set up in India by multinational corporations. India’s nearly 1,600 such units account for half the world’s GCCs, and employ about 1.6 million, or about 1,000 each.8 ‘GCC’ is a broad term, spanning low-skill back-office work, IT work, and research and development (R&D). Specific GCCs may do one or the other task, or combine more than one type of work.

There has been a dramatic rise in R&D work in GCCs in India, engaging over 0.5 million staff.9 According to the Financial Times, R&D capital expenditure by foreign firms in India rose more than 400 per cent in a single year, from $2.5 billion in 2021 to $12.9 billion in 2022. In that year, India supplanted the U.S., the number one for the past decade, as the top R&D foreign direct investment (FDI) destination; there are indications that this trend will continue.10 The incentive is lower labour cost: a software engineer’s salary in India is between $12,000 and $18,000 per annum, compared to the U.S. equivalent engineer’s salary of between $75,000 and $100,000.11 A Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) survey finds the number one reason for MNCs to invest in R&D in India is “availability of R&D talent pool at low cost”.12

However, the R&D carried out in the GCCs is largely unrelated to India, and does not provide impetus to Indian R&D capabilities. An observer notes that “GCCs continue to be linked directly to corporate headquarters or the headquarters of the strategic business unit. They have weak links to the MNC’s business in India.”13 A 2012 study of MNC R&D centres in India found that they had little connection with Indian institutions, and their R&D activities in India did not “reflect much importance of their Indian set-ups, or their interest in high-end R&D initiatives”. Indeed, their patents from activities in India accounted for just 0.5 per cent of their patents worldwide. The MNC R&D units maintain links with India’s university system, but not for the purpose of scientific or technological research inputs; rather, they do so in order to re-shape university education to generate more human resources of the type they require.14

As in the case of software exports, the main customer is the U.S., and U.S.-origin GCCs (global capability centres) account for 70 per cent of GCCs in India. U.S. firms feel comfortable with the environment in India: “India does not have Huawei-type companies that can challenge the pole position of global corporations in important new technologies. So, it is unlikely that we will face the kind of dispute we see on emerging telecom technologies between China and the U.S.”15 Nevertheless, foreign firms are anxious to protect their data from the Indian authorities, and hence “many GCCs have moved to a policy of storing all data on servers in the U.S. (or their parent country). In at least one GCC, computers located in the GCC have no data storage, and act more like ‘dumb terminals’ connected to the remote server.”16

What enters into the consumption of the IT worker

There is a wide range of skill levels and wages within the services exports sector. The GCCs include a large contingent of low-wage workers (earning as low as Rs 12,000 per month 17), and staff turnover is high, perhaps double of international levels.18 However, the wages of the better-paid workers in India’s digital sector are by Indian standards handsome (though a fraction of U.S. levels). The reason these wages are attractive to educated Indians is that many goods and most services are available in India at low prices, when expressed in U.S. dollar terms at the market exchange rate, i.e., $1 = Rs 83. That is, Rs 83 can buy more in India than $1 can buy in the U.S. Thus what is called the ‘Purchasing Power Parity’ (PPP) value of the rupee is higher than its market exchange rate value. Behind this seemingly benign phenomenon lies the fact that vast numbers of people in India, particularly in the informal sector, work for very low wages or returns, and therefore the things they make are cheaper. (The unpaid toil of women too hugely helps keep down the reproduction costs of the working class family.19)

So the Indian tech worker’s ability to enjoy a comfortable standard of living at a relatively low U.S. dollar wage (and therefore the foreign employer’s ability to hire him/her at that low dollar wage) depends on, in effect, a subsidy provided by India’s sweated informal sector and women’s labour.20 Without the vast reserve army of labour, as manifested in India’s low employment rate 21 and its vast informal sector, the wages of IT workers too would have to be higher, and the profits of firms outsourcing to India would be lower. In that sense, the continued growth of India’s IT industry depends precisely on its remaining an enclave, drawing on a large periphery. It is important to realise that the demand-suppressing policies by the Indian State, in the name of controlling the fiscal deficit and checking inflation, serve to maintain the reserve army of labour and keep down wage levels. In this fashion, the distorted pattern of development in India reproduces itself under imperialist domination.

Imperialist domination in the digital sphere

The dominant media have long associated certain ideological conceptions with the internet, such as freedom of individual expression and freedom of choice. One such conception is that the internet has put individuals worldwide on an equal footing; in the words of an American propagandist, “the world is flat”—an epiphany he claims to have had in India.22 The reality is that the digital world is marked by imperialist domination; and India is a prime example of this.

While several writers have talked of ‘imperialism’ or ‘colonialism/colonisation’ in the digital sphere, the meanings they have attached to these terms are very diverse, and, in some cases, divorced from a broader political-economic analysis of the world economy and politics. We take, as our frame, the relationship between the monopoly capital of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful countries and the mass of humanity in underdeveloped Asia, Africa and Latin America, a relationship which shapes the world’s material and financial flows, its physical environment, its cultural life and its political developments.

Over 100 years ago, Lenin, in his Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), described the process of concentration of capital in the later 19th century, which rendered the ‘free market’ a thing of the past. Giant monopolist associations emerged, backed by, or merged with, big finance. For their survival and growth, these monopolists were driven to seize the sources (and even potential sources) of raw materials and conquer foreign markets as well. All this was done with the help of State power. Foreign investment was an important instrument of extending monopoly hold. In this process, monopolists secured profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits, and so on—“economic territory in general”.

“In [the] backward countries”, said Lenin, “profits are usually high, for capital is scarce, the price of land is relatively low, wages are low, raw materials are cheap.” Even more important than the benefit the monopolists obtained by getting control of raw materials and markets was the benefit they obtained by denying their rivals access to the same. So they constantly strove to gain political influence, colonising countries, creating “spheres of influence”, and so on. Lenin remarked: “There are already over 100 such international cartels, which command the entire world market and divide it ‘amicably’ among themselves—until war re divides it.” Employing a historical-materialist method of analysis, he brought out the intertwining of economic and geopolitical aspects in the entire process.

The forms of imperialism may have undergone some change in the century since Lenin’s work, but there are striking continuities in its content. When we apply this perspective to India’s digital economy, we observe:

1. the creation of an international division of labour in the digital economy, whereby cheap labour power in India is used to raise the rate of profit of imperialist countries’ firms;

2. the domination of India’s market for digital goods and services by firms of the imperialist countries;

3. the capture and control of data, as a raw material, by these firms;

4. the use of foreign investment to capture economic territory in India;

5. the use of political influence to shut out rivals, if necessary even by war.

We have already discussed point 1 above. Let us look at points 2-5 below.

Hardware dependence

The hardware industry of computers, electronics, and optical products contributes to only 0.1 per cent of India’s gross value added (GVA).23 As Dhar and Joseph note, “While the ITES [Information Technology Enabled Services] segment of the Information Technology (IT) sector has performed exceptionally well, the other component of the industry, the Indian computer electronics industry, has not been able to establish itself as a distinct entity, despite its emergence in the 1960s.”24 This despite the glimpses of India’s technological potential in the performance of two institutions set up in the 1980s: the Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DoT), which was responsible for the initial spread of telephony in India till the 1990s, and the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC). Sudip Chaudhuri observes,

In the pre-reforms period, domestic manufacturing of telecom equipment was essentially sustained through public procurement and import substitution policies…. Mandatory purchase requirement did not make C-DoT less efficient. In fact C-DoT showed that it is possible not only to develop technologies as per international standards. The products can be cheaper and more suited to Indian conditions.25

Meanwhile, in the face of the denial of supercomputer technology by the U.S. and Japan, the C-DAC produced the Param supercomputer in 1991; “From its very first generation,”, Dhar and Joseph observe, the “Param supercomputer was ranked among the best machines in the world”.26 While these instances were not part of a comprehensive programme of building independent manufacturing capacity, they did provide glimpses of what is possible if one wants to promote indigenous capabilities.

The period of liberalisation and globalisation, however, saw India turn to near-complete dependence on imports of telecom gear and computer electronics.27 The ‘Make in India’ programme announced by the Prime Minister in 2014 claimed it would make India into a global manufacturing hub, including the domestic manufacture of mobile phones. Superficially, there was a sizeable increase in such ‘manufacture’; but in fact, import dependence only deepened, as a 2020 study by Sunil Mani brought out:

Domestic production has been dependent on parts that were imported from abroad, and these imports have been growing [imports of parts of mobile phones rose from $2.67 billion in 2014 to $11.56 billion in 2018]. Given the fact that production is largely based on imported inputs, the ratio of gross value added (GVA) to gross value of output (GVO) has been declining sharply, especially during the period when domestic output has been increasing [GVA/GVO declined from 17 per cent in 2013-14 to 13 per cent in 2017-18]…. As such, no domestic production or innovation capability has been created or is in the offing in the foreseeable future. This dependent development has led to India’s technology trade deficit increasing on account of increased royalty and licence fee payments, besides dividends and profits being repatriated abroad.28

Indeed, an RBI study of India’s digital economy noted indications of increasing in import dependence between 2014 and 2019 in computers, electronics, and optical products.29

In 2020-21, during the Covid lockdown, the Indian government announced a ‘Production-Linked Incentive’ (PLI) scheme, the stated aim of which was, once more, to promote manufacturing in India. There appeared to be a dramatic improvement in India’s net exports (i.e., exports minus imports) of mobile phones, from -$3.3 billion in 2017-18 to a $9.8 billion in 2022-23—a turnaround of $13.1 billion. The turnaround started in 2018-19, when import tariffs on mobile phones were raised, and accelerated in 2020-21, after the PLI scheme was announced.

However, an analysis by Raghuram Rajan, Rohit Lamba and Rahul Chauhan of mobile phone manufacturing in India reveals that, in the same period, the import of inputs for mobile phones (semiconductors, printed circuit board assemblies [PCBAs], displays, cameras and batteries) rose steeply. The combined net exports of mobile phones + inputs in fact sharply worsened, from -$12.7 billion in 2016-17 to -$21.3 billion in 2022-23; thus “it is entirely possible that we have become more dependent on imports during the PLI scheme!” Even after providing for various other possibilities, the net figure of exports remains negative. Moreover, Rajan et al. point out that the PLI subsidies are expressed in terms of the final value of the phone, not on the value added in India. The manufacturing cost of an Apple iPhone 12Max is only one-third the value of the phone, value added at the stage of assembly is only 4 per cent of the manufacturing costs; that is, assembly would amount to only 1.33 per cent of the final value of the phone. Whereas PLI subsidies are initially 6 per cent of the value of the phone, falling by the end of five years to 4 per cent, of the value of the phone. Since only assembly appears to be taking place in India, the subsidies may well be larger than the value added.30 Moreover, state governments add to the PLI subsidies by providing tax incentives, power and subsidised land.

As we shall see later in this article, the western imperialist countries used their political influence to shut out rivals from the Indian telecom market, bearing out Lenin’s political-economic analysis.

Capture of the digital market

In October 2015, the Indian Prime Minister visited Silicon Valley in the U.S., home to Big Tech, where he received a rousing reception. As former Infosys chief financial officer, T.V. Mohandas Pai, rapturously explained:

Why was there this great interest in Mr. Modi in the Valley? Well, Americans, Indians, and techies saw in him a tech-savvy leader who was pro-business, decisive, articulate, charismatic and who exuded strength. They recognised that India was the last great, unconquered digital market after China and Prime Minister Modi’s Digital India project could empower 1.25 billion people in India digitally…. They all wanted a piece of the action. So, Microsoft, Facebook, Google and Apple, who want to own the whole world digitally, saw in Mr. Modi the answer to their dreams.31

India’s digital market is overwhelmingly captured, or, to adopt the term Michael Kwet uses in the context of South Africa,32 “colonised” by a handful of U.S. multinationals. Table 1 presents the shares of different U.S. firms in India’s digital market:

(much, much more at link. Table don't c&p worth a damn.)

https://mronline.org/2024/05/28/digital ... a-part-iv/

*******

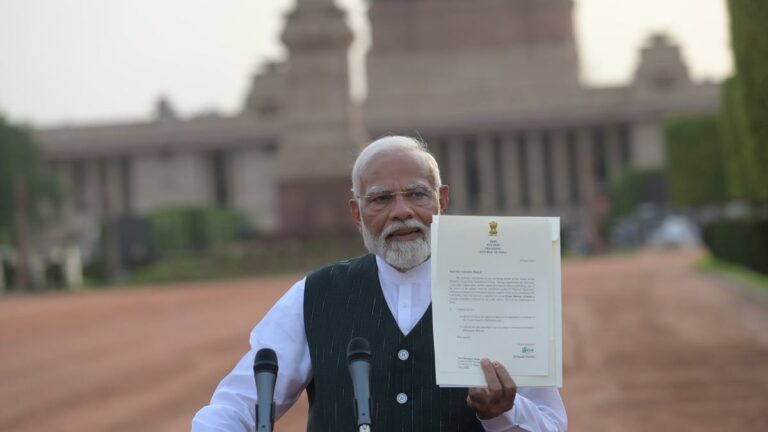

Modi’s latest campaign message to supporters: ‘God has sent me’

By Rhea Mogul, CNN

Updated 1:46 AM EDT, Tue May 28, 2024

India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses his supporters during an election campaign rally in Pushkar on April 6, 2024, ahead of the country's upcoming general elections. (Photo by HIMANSHU SHARMA / AFP) (Photo by HIMANSHU SHARMA/AFP via Getty Images)

Popular but polarizing: Hear what Indians say about Modi

04:20 - Source: CNN

—

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has a new message for supporters on the campaign trail: God has chosen him.

“I’m convinced that God has sent me for a purpose, and when that purpose is finished, my work will be done,” he told local news channel NDTV in an interview last week. “This is why I have dedicated myself to God.”

Modi continued: “God doesn’t reveal his cards. He just keeps making me do things.”

Since assuming power in 2014, Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have promoted a strident brand of Hindu nationalism in a country where about 80% of the population are followers of the polytheistic faith.

And while he has used such language in the past, his message of being a leader chosen by God has become much more apparent as attempts to win a third consecutive five-year term in power.

Throughout India’s mammoth weeks-long national election, which declares results on June 4, Modi has given multiple media interviews and speeches that echo the comments made to NDTV.

He has taken on the persona of an openly devout Hindu, said Subir Sinha, Director of the South Asia Institute at SOAS University of London. This, he added has “rallied his base who feel pride in such religiosity.”

India is a deeply religious country. But historically its post-Independence leaders have remained publicly secular, in part to avoid being seen to pander to any one side in a nation with a long history of inter-religious violence.

“(He is) the first prime minister, they say, to be unashamed about this faith,” Sinha said.

When he first contested elections a decade ago, Modi chose India’s spiritual capital Varanasi as his constituency, making the ancient city the perfect backdrop to meld his religious and political ambitions.

“Mother Ganga has called me to Varanasi,” Modi said at the time, referring to the holy Ganges River, considered to be the body of the Hindu deity Ganga by many followers of the faith.

Standing on its banks earlier this month, Modi made another reference to his perceived divinity.

“Until my mother was alive, I had believed that perhaps my birth was a biological one,” Modi told CNN affiliate CNN News-18. “But after her death, when I look at my life experiences, I’m convinced that God has sent me here.”

God has, Modi said, made him “nothing but an instrument.”

Modi’s grandest display of divinity was on display in January this year, when he consecrated the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, a controversial Hindu temple that was built on the site of a destroyed mosque.

Billboards celebrating the temple’s opening featured an image of Hindu deity Ram alongside Modi’s face, with the leader of his BJP even dubbing the prime minister “The King of Gods.”

Modi fasted for 11 days in a purification ritual before the event and visited temples across the country, performing customs sacramental to India’s majority faith. He publicly called himself “an instrument” of Lord Ram, picked by the divine to “represent all the people of India.”

At the consecration, Modi presided over the “Pran Pratishtha” – the unveiling of the much-anticipated Ram idol – taking on a role typically reserved for priests.

During the election Modi has also sparked a row over hate speech when he accused Muslims – who have been part of India for centuries – of being “infiltrators,” and echoing a false conspiracy voiced by some Hindu nationalists that Muslims are displacing the country’s Hindu population by deliberately having large families.

It ignited widespread anger among Muslim leaders and opposition politicians and calls for election authorities to investigate. BJP party spokespeople subsequently said Modi was talking about undocumented migrants. The election commission has asked the BJP to respond to the allegations.

https://us.cnn.com/2024/05/28/india/ind ... index.html

Easy to see that the West, through it's media, is punishing the Indian government for not joining the anti Russo-Chinese alliance wholeheartedly. It's shooting fish in a barrel but you never heard this stuff until they got mad at Modi.

(amusing that a 'Mogul' would pen an anti-Modi piece.)