Posted on June 28, 2025 by Yves Smith

Yves here. This piece provides an in-depth look at ecotourism, with emphasis on the fact that despite its lofty promises, it often does more harm than good. There’s also a class warfare implication: the very high end treks are the ones which are in a position to do minimal damage and produce a net environmental positive. However, articles like this to do not seem to factor in carbon emission effects of high end (as in front of the bus or private class flier) getting to and from remote locations.

And it’s not just that ecotourism is regularly environmentally extractive, despite pretending the reverse. These schemes are routinely economically extractive, in a developing economy analogue to China’s, and now Russia’s and India’s so-called “zero dollar tours,” where travel packages to Southeast Asia are structured so as to maximize benefits to China and minimize benefits to the host country.

This article does stress that it is possible to have ecotourism indeed be net positive, and cites Costa Rica and Uganda as examples of how to achieve that on a large-scale basis.

By Kate Petty, an educator, writer, yoga teacher, and environmental activist who has worked with the New York Nature Conservancy and various United Nations initiatives, including UNICEF, the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Universal Versatile Society to promote education, social justice, and solution-oriented projects for a healthier planet. She is a contributor to the Observatory. Produced by Earth | Food \ Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute

Ecotourism is often hailed as a sustainable alternative to traditional travel—an opportunity to explore unique environments while supporting local communities and conservation efforts. Yet beneath its green image lies a more complex and often troubling reality. When poorly managed, ecotourism can inflict more harm than good, undermining the very ideals it seeks to uphold.

The ecotourism industry has emerged as one of the fastest-expanding sectors within global travel. According to the Global Ecotourism Network, in 2023, eco-travel accounted for an estimated 20 percent of the international tourism market, with projections indicating continued double-digit annual growth. In 2023 alone, the global ecotourism market was valued at over $200 billion. Economic predictions estimate that the market could reach between $759 billion by 2032 and $945 billion by 2034.

Despite this rapid growth and economic promise, ecotourism enterprises have faced significant criticism from conservationists and researchers. In a 2020 Architectural Review article titled “Outrage: The Ecotourism Hoax,” Smith Mordak, chief executive of the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), asserted that “As long as the underlying principle behind tourism is to bring growth-stimulating inward investment, tourism cannot be made ‘eco.’”

The Ecotourism Paradox

Mordak’s remarks expose the deeper contradictions within many so-called “sustainable” initiatives, drawing attention to the pervasive issues of greenwashing and bluewashing. Just as corporations may falsely brand themselves as environmentally friendly or socially responsible to appeal to conscious consumers, ecotourism companies often mask exploitative or unsustainable practices behind the veneer of conservation. Ultimately, without a fundamental shift in the economic principles that underpin ecotourism, efforts to make the industry sustainable risk becoming performative, focusing on marketing rather than achieving meaningful impact.

According to UKGBC’s Mordak, “Like everything else nurtured in the agar jelly of capitalism, noble intentions soon become corrupted, and the ‘eco’ prefix amounts to little more than a greenwashing rebrand.”

Ecotourism is built on a dual promise—to protect natural environments and to share them with visitors—yet fulfilling one often puts the other at risk. In April 2025, I interviewed Dave Blanton, founder of Friends of the Serengeti. He started the organization in response to a proposed commercial highway through Serengeti National Park, a development that would have fragmented the ecosystem and destroyed critical migratory routes. He explained the paradox: “On one hand, the growth of tourism in the Serengeti-Mara region will generate government revenue and create jobs. On the other hand, it will increase environmental pressure and diminish the traveler experience.”

Blanton, whose connection to the Serengeti spans over four decades, said, “It is difficult to ensure high standards and best practices in the face of increased demand, competition, and overly ambitious goals for growth.

Grassroots Origins, Global Ideals

Rooted in principles of sustainability and community engagement, grassroots ecotourism, which emerged in the early 1980s, was developed as a response to growing global concerns about environmental degradation and the negative impacts of mass tourism. It emphasizes low-cost, purpose-driven travel experiences that foster direct contributions to conservation and local development.

The current grassroots volunteer travel industry—often referred to as “voluntourism”—continues to attract socially conscious travelers seeking meaningful, hands-on experiences that contribute to local communities and conservation efforts. Programs typically involve small-scale, community-led initiatives that prioritize local needs, such as wildlife monitoring, habitat restoration, education, or sustainable agriculture, and take the form of educational exchanges or participation in field research.

Volunteer travelers opting for low-cost expeditions may pay between $20 and $50 per day, which usually covers necessities such as meals, local transportation, and accommodation. Lodging in these programs is typically modest, ranging from rural homestays and shared guesthouses to dormitory-style lodgings or even tents, depending on the location and nature of the work.

Some who have participated in volunteer travel expeditions have reported a lack of resources and infrastructure, which leaves both volunteers and host communities struggling to meet basic needs. Poorly managed programs are another common complaint, with some volunteers arriving to find disorganized projects, minimal supervision, and unclear objectives. Especially troubling is that some wildlife conservation programs have been accused of neglecting animals by housing them in inadequate enclosures—small, unsanitary, or unsafe spaces that can cause stress, injury, or behavioral problems.

Conservation or Commercial Growth?

Increasingly, however, the voluntourism model is being supplanted by the proliferation of large-scale, high-end commercial ventures, where travelers are observers rather than helpers. The modern ecotourism landscape is increasingly dominated by luxury enterprises, some of which feature elegant eco-lodges, boutique resorts, and nature-based retreats offering the comforts of premium hospitality.

Accommodations are often situated in remote, pristine environments, such as nature reserves, rainforests, or coastal regions. Amenities may include private villas or bungalows, gourmet organic cuisine, private wildlife excursions, and wellness offerings like yoga and spa treatments. Prices for these luxury experiences can range from several hundred to several thousand dollars per night.

With the expansion of major hotel chains and multinational businesses in conservation areas, critics argue that the scale and infrastructure required to sustain such operations can strain fragile ecosystems and disrupt local communities and wildlife.

Matt Kareus, executive director of the International Galápagos Tour Operators Association (IGTOA), focuses his efforts on preserving the unique biodiversity of the Galápagos Islands through education, policy advocacy, and collaborative conservation initiatives. When I spoke to him in April 2025, he stated that the most serious long-term threat to the Galápagos is runaway tourism growth, which has compromised the natural resources and local infrastructure on the Ecuadorian islands. Like Blanton, Kareus emphasized the need for stricter environmental standards and accountability to ensure that ecotourism remains a tool for conservation, rather than a vehicle for unchecked commercial growth.

Kareus says that the issue is not whether luxury ecotourism is necessarily better or worse than other forms of tourism; instead, it’s a matter of how well tourism itself is managed and regulated in individual regions.

“There are a lot of potential benefits when it’s done thoughtfully and responsibly, just as there can be a lot of downsides to more budget-friendly modes of tourism if they aren’t done in the correct way,” said Kareus, who offered an example: “Imagine a 15-room eco-lodge surrounded by a nature reserve—it could potentially generate similar economic and employment benefits as a standard 100-room hotel, with far less negative impact on the surrounding environment.”

Luxury ecotourism developments are increasingly incorporating advanced eco-friendly design, planning, and investment strategies, emphasizing features such as solar energy systems, rainwater harvesting, passive cooling architecture, the use of locally sourced and renewable building materials like bamboo or reclaimed wood, as well as carbon offset programs. Operators assert that strategic site planning minimizes ecological disruption by preserving native vegetation, protecting wildlife corridors, and adhering to low-impact construction methods.

The Commodification of Culture

While mass-market ecotourism promises immersion in natural environments and meaningful cultural exchanges, some critics argue that the result is often a curated version of nature and culture—polished, exclusive, and often removed from the realities of place.

Researchers attribute this conceit to the “white savior complex,” a mindset—often held by well-meaning but misinformed Western travelers—where they perceive themselves as heroic figures “rescuing” impoverished or marginalized communities, particularly in the Global South, through short-term volunteerism or conservation work, but often end up reinforcing colonial-era power imbalances, where Western values, knowledge, and presence are seen as superior or necessary for progress. At the same time, local expertise, autonomy, and cultural practices are undervalued or ignored.

In my interview with her in May 2025, Michelle Mielly, professor of law, management, and social sciences at Grenoble Ecole de Management (GEM), commented, “Indigenous people want to be left alone. We keep colonizing these cultures.”

Commodification not only undermines the integrity of local traditions but also distances travelers from the raw, unfiltered experiences that make travel transformative, turning sacred rituals and cultural practices into spectacles for outsiders. Academic researchers refer to the practice as “cultural extractivism”—the appropriation of Indigenous cultural practices and traditions by commercial enterprise.

Professor Mielly offered an instructive example in the increasing popularity of ayahuasca retreats in the Amazon River Basin. Ayahuasca, a psychedelic brew made from native plants that has been used for centuries by Indigenous tribes for its spiritual and therapeutic properties, is being successfully marketed to Western tourists as a psychedelic substance that promises a mind-altering experience worth traveling for.

According to studies, ayahuasca has demonstrated antidepressant effects, offering hope for many who don’t react to classic interventions. Retreats are often hosted in remote jungle settings in countries like Peru, Brazil, or Colombia, and are led by Indigenous shamans or facilitators trained in local spiritual and healing practices. However, Mielly explains that the significance of the Amazon rainforest extends far beyond its role as a habitat. “[Indigenous communities] derive their culture, language, and social order from the natural structure of the forest,” she says.

Preservation Without Permission

In many cases, protected areas are established or expanded to accommodate ecotourism without the full consent or involvement of the people who have historically lived on and stewarded the land. This has led to the displacement of Indigenous groups, stripping them of access to ancestral territories and traditional livelihoods under the guise of environmental preservation.

“While it’s no surprise that the original concept of ecotourism has been obscured by less virtuous projects, they become more problematic when they block local communities from ancestral lands or even involve their forced relocation,” wrote Mielly in a 2023 article in The Conversation. Mielly cites several examples of forced displacement of Indigenous populations under the crush of ecotourism development—including the eviction of 16 villages on Rempang Island, Indonesia, to make way for a solar panel factory and “eco-city.”

“Eco-projects are not necessarily humanitarian projects,” noted Mielly, invoking how the three pillars of sustainability—environmental, social, and economic— are not always upheld within the ecotourism industry. Together, these pillars support the goal of meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. But Mielly is cautious. “We are so lucky to have Indigenous people,” Mielly says. “They are our past, our future, and the key to our survival.”

“A Contest for Land”

Major infrastructure projects are increasingly encroaching on ancestral lands, displacing Indigenous communities and cutting them off from traditional territories and livelihoods, says Mielly, noting that “a contest for land is a contest for life; ecotourism is an invasion of these spaces.”

To study the ways in which poorly regulated ecotourism initiatives can reinforce historical patterns of exclusion and dispossession, Mielly and a team of researchers from GEM organized a dialogue with members of the Mbyá Guaraní community in the coastal region of Maricá, Brazil, to examine how business schools and multinational corporations influence Indigenous land rights.

The discussion centered on the Mareay project — an ambitious proposal to develop a vast coastal area through partnerships with major hospitality companies, which will include five luxury hotels, a resort with a golf course, residential units, an education complex, a health center, and a commercial area. Mielly cautioned that the “Disneyfication” of ecotourism ventures on the scale and scope of the Mareay project raises critical questions about the harm ecotourism developments inflict on coastal landscapes, local livelihoods, and Indigenous ways of life.

“When we have great income inequalities, ecotourism becomes ethically challenging,” said Mielly. “This is where we have to shift our gaze. Indigenous people want to be left alone. They don’t understand the value of these enterprises engulfing their communities, and if they do, they may take large cash settlements, but they lose their land,” she said, adding, “We keep colonizing these cultures.”

Infrastructure & Impact

This tension mirrors broader patterns observed across Latin America, where ambitious infrastructure projects often claim to be sustainable while dramatically reshaping environments and economies.

Increasingly, governments and private stakeholders are developing and investing in new airports, eco-friendly lodges, and transportation networks. These developments aim to strike a balance between supporting economic growth through tourism and protecting the ecosystems that attract visitors. However, studies suggest that large-scale infrastructure projects could shift the tourism model from high-value, low-impact travel to runaway mass tourism, with irreversible environmental and sociocultural consequences.

For instance, in preparation for hosting the COP30 climate summit in November 2025, Brazil is constructing the Avenida Liberdade, a four-lane highway through protected Amazon rainforest near Belém, designed to improve access for an anticipated 50,000 attendees. The project includes wildlife crossings, bicycle lanes, and solar-powered lighting.

The highway has sparked controversy due to its ecological impact on the rainforest. Local resident Claudio Verequete told the BBC that he used to make an income from harvesting açaí berries from trees that once occupied the land where the highway is being constructed. “Everything was destroyed,” he said. “Our harvest has already been cut down. We no longer have that income to support our family.” Verequete added that he has received no compensation from the state government, and he worries the construction of the road will lead to more deforestation in the future.

Venezuela is also investing in infrastructure within ecologically sensitive areas. According to a 2024 Reuters article, Los Roques National Park is undergoing massive development to attract tourists, including the expansion of airport runways and the construction of hotels. The government’s promotion of these projects as eco-friendly contrasts with criticisms from environmental groups regarding their social, economic, and ecological impact, as they have led to damage to coral reefs, mangroves, and endangered turtle nesting sites.

Sharing the Wealth

When ecotourism aligns conservation goals with community development, it can generate significant social, economic, and environmental benefits—but without effective revenue-sharing mechanisms, the wealth often flows to tour operators or foreign investors, leaving residents with limited economic gains, minimal decision-making power, and few long-term benefits from conservation efforts.

By allocating a fair share of profits to those who live in and around conservation areas, revenue sharing fosters community support for environmental protection and discourages unsustainable practices such as poaching, deforestation, or illegal land use.

Despite their potential to support local communities, revenue-sharing systems are vulnerable to corruption and exploitation. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) initiative Targeting Natural Resource Corruption (TNRC), implemented from 2018-2024, environmental corruption offenses range from misallocation of conservation funds to the exploitation of natural resources and local populations, which TNRC attributed to “weak governance, lack of transparency, and poorly enforced regulations that allow unscrupulous operators and officials to profit at the expense of the environment.” Without well-managed revenue sharing, funds intended to benefit conservation efforts and local populations may be diverted, exacerbating inequalities.

While revenue sharing provides immediate benefits to communities, it is the integration of models like Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) that offers a more sustainable, long-term approach by empowering local populations to take active roles in managing and protecting their natural resources. Central to this model is the recognition of community ownership or rights over land, wildlife, or marine resources.

Namibia’s CBNRM program is widely recognized as one of the most successful examples of integrating ecotourism with community development and conservation. Launched in the 1990s, the program grants legal rights to local communities, organized into conservancies, to manage and benefit from wildlife and natural resources on communal lands. Through partnerships with private ecotourism operators and sustainable hunting concessions, these conservancies generate significant income that is reinvested into local infrastructure, education, healthcare, and conservation efforts.

According to a report from Community Conservation Namibia, in 2022 alone, tourism activities generated approximately $6 million in revenue for communities across 86 registered conservancies. Lodges, safari operations, and guided wildlife experiences provide direct employment for thousands of rural Namibians while also funding community-wide initiatives. Crucially, the program has created powerful incentives for conservation: as wildlife populations have rebounded, such as the growth of free-roaming desert lions and black rhinos, tourism revenue has increased, reinforcing a cycle of ecological and economic sustainability.

Beyond the Footprint: Ecotourism’s Positive Legacy

Despite the risks that ecotourism poses, it has also helped catalyze important gains in education and sustainable development in some areas. Volunteer travel, in particular, has brought resources, skills, and knowledge to remote regions, supporting the development of sustainable agriculture, architecture, renewable energy projects, and waste management systems.

Costa Rica stands out as a global leader in ecotourism, recognized for reinvesting tourism revenue in national parks and local communities. While challenges like corruption persist, Costa Rica has made ecotourism a central element of its national identity and development strategy, often cited as a model for sustainable tourism worldwide.

For instance, in Costa Rica, the ecotourism industry has funded educational programs and conservation initiatives, including the Monteverde Institute, which offers community-based research and educational programs in sustainability, ecology, and cultural heritage.

In Tortuguero, a once-remote Caribbean village in Costa Rica, sea turtle ecotourism has played a pivotal role in improving both environmental and public health outcomes. According to the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC), revenue generated from guided turtle-watching tours and eco-lodges has helped fund essential services, including local health clinics and clean water systems. Organizations like STC have expanded their efforts beyond wildlife protection to include environmental education initiatives that address public health concerns, including waste management and mosquito-borne disease prevention.

Uganda has strategically leveraged ecotourism to strengthen local community infrastructure through the Bwindi National Forest Park, which generates revenue from gorilla trekking permits that support both conservation efforts and community health clinics, such as the Bwindi Community Hospital, which now serves tens of thousands of people with maternal care, HIV treatment, and preventive health services.

Sustainable Travel, Shared Futures

While ecotourism revenue cannot replace the reach and impact of international aid, it may be a valuable complementary strategy for building resilience, fostering self-reliance, and supporting long-term development, especially when integrated with education, conservation, and community governance efforts. “Good ecotourism educates us,” says Mielly, as travel networks can lead to long-term partnerships, funding, and knowledge-sharing that transcend cultural and national boundaries.

Notably, some for-profit commercial travel companies actively fund vital health and social programs in impoverished global communities near conservation centers. G Adventures, an international adventure travel company, partners with its non-profit Planeterra Foundation to support health and education projects in over 100 countries. Their initiatives include building water tanks in Panama, combating child sex tourism in Cambodia, and helping women weavers in Peru.

Intrepid Travel, a certified B Corporation, operates small-group tours worldwide with a strong commitment to responsible tourism. Through its non-profit arm, The Intrepid Foundation, the company has funded various health-related initiatives. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the foundation provided essential medical equipment, including oxygen tanks, to communities in India and delivered food packages to families in remote parts of Peru. Micato Safaris, a luxury safari operator in Africa, runs the AmericaShare program, which aids communities affected by HIV/AIDS in Kenya. For every safari sold, Micato sends a child to school and supports local clinics and meal programs, directly impacting community health and education.

Keeping Eco Ethical

The success of ecotourism is contingent upon the ways it integrates its benevolent vision into the development process. In some cases, well-managed ecotourism can promote conservation and economic benefits simultaneously. In other cases, it can inadvertently lead to environmental degradation, cultural erosion, and economic disparities if not adequately regulated.

Several reputable organizations, certifications, and frameworks help determine the legitimacy, ethical standards, and quality of volunteer travel companies. Some organizations are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Others are certified B Corporations, which undergo a rigorous accreditation process that evaluates social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency.

Various bodies have emerged to define, regulate, and certify best practices in ecotourism, such as the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), Rainforest Alliance, and Travelife, which establish transparent guidelines that prioritize ethical business practices and hold companies accountable in the ever-growing, high-stakes industry.

Through comprehensive criteria, organizations like the GSTC define what qualifies as “sustainable” or “eco-friendly” tourism, covering environmental protection, cultural respect, fair labor practices, and local economic development. Additionally, they assess and certify tour operators, accommodations, and entire destinations to ensure they meet these standards.

These regulatory bodies often conduct audits and ongoing assessments to ensure compliance, which helps prevent greenwashing by providing training and support to help tourism providers improve their sustainability practices, especially in developing regions where resources may be limited.

Look Beyond the Label: Vetting Ecotourism

Certifications serve as a credibility marker for consumers seeking responsible travel options. Experienced conservationists strongly advise prospective ecotourists to thoroughly research and evaluate the credentials, practices, and ethical standards of ecotourism organizations to ensure that their travel choices genuinely support conservation efforts, benefit local communities, and minimize ecological harm.

IGTOA’s Kareus cautions that it is essential to dig deeper and ask questions: “How are they giving back to the communities where they operate? How do they ensure that the economic benefits of what they are doing are shared as broadly as possible in those communities? Do they have programs in place to help support conservation, or community development, or to reduce any potential negative impacts of their operations?” are a few he suggested.

Blanton, Kareus, and Mielly all agree that companies are doing excellent work and genuinely making a positive impact. As Mielly notes, “Good ecotourism educates us,” reminding travelers of their role in fostering awareness and respect. Yet she also adds that “eco starts at home,” underscoring the idea that sustainable values must begin with personal responsibility and not just be outsourced to the places we visit.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2025/06 ... lanet.html

******

Vijay Prashad: Beyond ‘Green Capitalism’

June 27, 2025

The term “Anthropocene” implies that humans — as an undifferentiated whole — have created the ecological crisis. This downplays the role of the capitalist system and its class and national divides.

Rebecca Lee Kunz, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, Coyote Skin – Dusty Paws, 2022.

(Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

Reading documents from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) makes me morose. Everything looks terrible. This is largely due to the social processes set in motion by capitalism, including the harsh use of nature and the reliance on carbon-based fuels. For example:

One million of the estimated 8 million species of plants and animals on the planet are threatened with extinction.

The main threat to a majority of species at risk of extinction is biodiversity loss caused by the capitalist agribusiness system of food production.

Agricultural production — currently accounting for more than 30 percent of the world’s habitable land surface – is responsible for 86 percent of projected losses in terrestrial biodiversity because of land conversion, pollution, and soil degradation.

These are three out of hundreds of points that could be made from as many scientific documents. It is important to emphasise that environmental degradation has not been caused by humans in general, but by a certain system of organising society which we call capitalism.

Michael Armitage, Kenya, Dandora or Xala, Musicians, 2022. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

The problem with the term Anthropocene (which began to be used first by scientists, then by social scientists) is that it implies that humans — as an undifferentiated whole — have created the ecological crisis we are facing. This subtly downplays the role of the capitalist system and its accompanying class and national divides.

However, data show that humanity is using the equivalent of about 1.7 Earths to sustain our current consumption levels. In other words, we are consuming natural resources 75 percent times faster than nature can regenerate them each year.

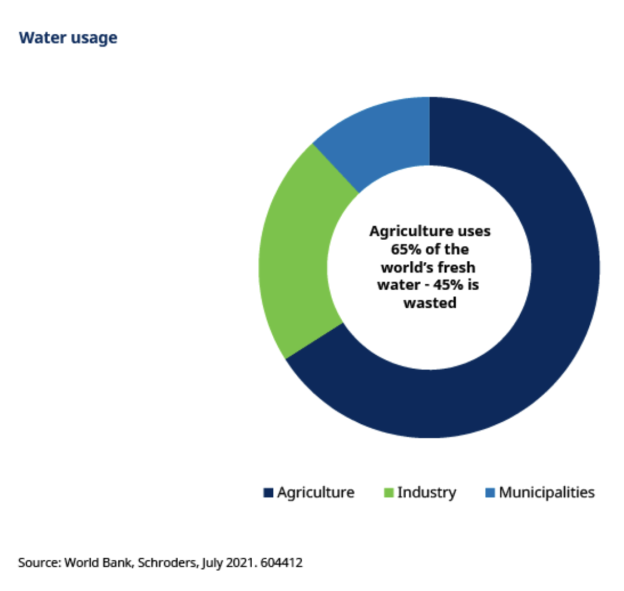

Unless we find another habitable planet, there is no arithmetic way to solve the problem. This is not a matter of the climate alone, but also of the environmental stress we have placed on the Earth (such as through deforestation, overfishing, overuse of fresh water, and soil degradation).

If we break this undifferentiated concept of humanity down by country, clear divisions emerge. If everyone lived like an average person in the United States, then we would need five Earths. If everyone lived like an average person in the European Union, we would need three Earths. If everyone lived like an Indian, we would need 0.8 Earths. If everyone lived like a person from Yemen, we would need 0.3 Earths.

An undifferentiated concept of humanity disguises the great differences across the world and suppresses the need of some peoples — such as in Yemen — to increase their consumption in order to have a dignified life.

The concept of the Anthropocene masks more than it reveals.

Roger Botembe, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Les Initiés, 2001. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

In a few months, private jets will land in Belém, Brazil, for the U.N.’s annual conference on climate change. Situated at the estuary of the Amazon River, Belém is an ideal location for “COP30,” the 30th year of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Over the past quarter century, the Amazon region has suffered from terrible deforestation, with the Brazilian Amazon alone experiencing total forest loss of 264,000 square kilometres from 2000 to 2023 — equivalent to the combined area of New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Brazilian President Lula da Silva’s intensive programme of conservation has made considerable advances in reversing this trend, but it needs to go further. Holding COP30 in Belém will be a strong message not only to save the Amazon but to highlight the future of the planet and of humanity.

Our team in Brazil is currently working on a series of publications on the capitalist crisis of climate and the environment to be distributed at COP30. It is already clear from our analysis that there is no solution to be found in “green capitalism,” as Jason Hickel wrote in one of our Pan African newsletters, it is capitalism itself that is the problem we face. Below, please find some preliminary demands that go beyond the façade of green capitalism.

Jagath Weerasinghe, Sri Lanka, Celestial Underwear, 2003.

(Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

1. Climate and environmental discussions must be democratised. There is no room for closed-door meetings financed by corporations that have a vested interest in environmental and climate destruction. For instance, COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, was partly funded by oil companies such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, Octopus Energy, the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan, and TotalEnergies as well as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the World Economic Forum (itself partly funded by the U.S. government). Whoever pays the piper calls the tune, an adage that is not meaningless when it comes to money and power. Such a U.N. conference must be funded by governments and transparent about the conversations taking place in all meetings.

2. The world’s governments must strengthen their own agreements and treaty obligations. It is important to note that due to the pressure from the U.S. and EU, none of the major climate agreements adopted strong language for compensation, or what is known as “loss and damage” (i.e., climate reparations). Contributions to the loss and damage fund are voluntary, as reflected by a number of processes and treaties from the 1992 UNFCCC to the 2013 Warsaw International Mechanism, 2015 Paris Agreement, 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact, and the 2022 Loss and Damage Fund agreement.

Denilson Baniwa, Brazil, Awá uyuká kisé, tá uyuká kurí aé kisé irü or whoever hurts with iron will be hurt with iron, 2018. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

3. There must be a fair energy transition plan that is democratically shaped. Such a plan must include ending governments subsidies for private carbon-based fuel companies. Instead those funds must be used to promote a new energy matrix and protect communities from the adverse impact of the climate and environmental catastrophe.

4. The global economy must be reshaped through agrarian reform. Such a reform must emphasise a science-based and democratic form of agriculture that protects the soil, water and air. Governments must carry out studies to assess what it means to restructure agriculture in order to address the climate and environmental catastrophe. We need new forms of agro-climatic mapping and data to help us understand how to harness local communities’ knowledge to protect the natural ecosystem while finding ways to sustainably use natural resources for the benefit of all.

Such a mapping exercise will help us better understand how to combat deforestation and promote reforestation, how to properly harness water resources for our own consumption and energy, and how to regulate mining activities to draw resources from the earth without causing catastrophic social and environmental destruction. Can we, for instance, pledge to reach net-zero deforestation by 2027?

Sebastião Salgado, Brazil, Valley of Javari Indigenous Territory, State of Amazonas, 1998. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

The photograph above is by our friend Sebastião Salgado (1944–2025), who died on May 23. Salgado portrayed the working class and peasantry with dignity and without romanticising their exploitation. He was always in solidarity with their struggles and organisations.

After the 1996 Eldorado do Carajás Massacre, in which police and gunmen who had been hired by powerful companies killed 19 activists connected to the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movement dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, or MST) in South Pará, Salgado, alongside the singer Chico Buarque and the writer José Saramago, created a book called Terra (Land), the proceeds of which went to the MST. This, alongside Salgado’s donation of some of his photographs, helped the MST build its Florestan Fernandes National School.

Salgado greatly enjoyed the work of Tricontinental and would occasionally send a note of appreciation for the materials we produce. We bow our heads in respect for his great contributions to humanity.

In 1843, a man named Julio Cezar Ribeiro de Souza was born in Belém, on the other side of the Amazon from the Vale do Javari that Salgado photographed. Souza loved to watch birds fly, and it was this close observation of nature that provided him with the inspiration to invent the steerable hot air balloon, mimicking birds’ aeronautics. Perhaps we need to cultivate this ethos: nature does not need to be conquered; it must be learned from and lived through.

https://consortiumnews.com/2025/06/27/v ... apitalism/

*****

Can carbon dioxide removal save the climate?

June 29, 2025

Beyond wishful thinking: Can technology stop global heating by sucking CO2 out of the air?

Climeworks CO2 capture plant under construction in Iceland.

by Ian Angus

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the world’s atmosphere is now very close to 429 parts per million.[1] That’s not just the highest level ever directly measured, it’s the highest in more than three million years, higher than humans have ever experienced.

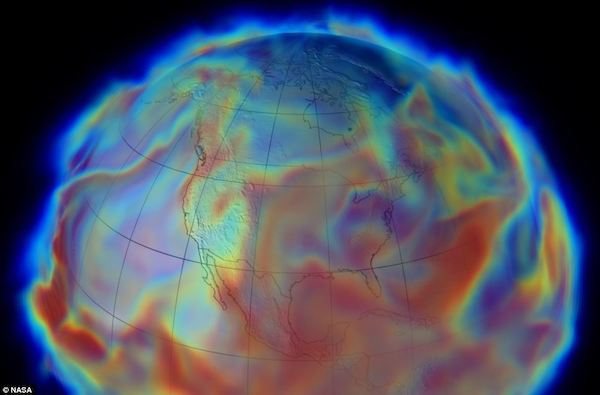

That’s a direct result of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry, which reached a record 37.4 billion metric tons in 2024.[2] The world’s oceans, plants, and soils absorbed more than half of that, but the CO2 that stayed in the air increased the total by about 15 billion metric tons, further fracturing the global carbon cycle and intensifying what the UN Secretary-General says should now be called the era of global boiling.[3]

If all anthropogenic emissions were to stop tomorrow, natural processes would gradually reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere to safer levels, but the key word is gradually. As a leading climate scientist writes, “The lifetime of fossil fuel CO2 in the atmosphere is a few centuries, plus 25 percent that lasts essentially forever.”

“The climatic impacts of releasing fossil fuel CO2 to the atmosphere will last longer than Stonehenge. Longer than time capsules, longer than nuclear waste, far longer than the age of human civilization so far. Each ton of coal that we burn leaves CO2 gas in the atmosphere. The CO2 coming from a quarter of that ton will still be affecting the climate one thousand years from now, at the start of the next millennium.”[4]

Other scientists put the very long-lasting fraction at 20 percent, but that is a trivial difference given that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is now a trillion tons greater than when direct measurements started in 1958. Many centuries from now, that CO2 will still be keeping the Earth’s temperatures well above pre-industrial levels.

The most widely promoted solution is variously called Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) or Negative Emissions Technology (NET)—synonyms for using technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Indeed, most plans advanced for keeping warming below 1.5 degrees include CDR as a necessary component. Climate policy planners in every country have accepted the fossil fuel industry’s argument that it is not practical to reduce emissions rapidly, so we must find some means of pulling CO2 back out of the air faster than it is emitted.

Most plans assume that global temperatures will rise higher than the target and later be pulled back by carbon dioxide removal technology. How much warmer will it get? How much longer will CO2 concentrations be unsafely high? How much irreversible damage will be done to Earth and its inhabitants in the meantime? No one offers encouraging answers to those questions.

The Economist, authoritative voice of free market capitalism, tells us that passing 1.5° “does not doom the planet … but it is a death sentence for some people, ways of life, ecosystems, even countries.” And for that reason, “Technologies to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, now in their infancy, need a lot of attention.”[5]

The editors of The CDR Primer argue that while priority should be given to cutting emissions, CDR must be deployed at the same time, because some industries will be unable to get to zero, “even with a massive global effort to cut climate pollution.”

“The scale of such emissions requires a massive investment in CDR, likely on the order of gigatons of CO2 removed per year by mid-century. Even larger amounts would have to be removed to draw down atmospheric concentrations from their peak after we reach net-zero global emissions.”[6]

That may be what we need, but what is actually possible?

If anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions continue, temperatures will rise unless concentration increases are matched by removals, which would require removing billions of tons of gas every year. Setting aside the obvious barriers of politics and cost, what physical requirements would have to be met for CDR to stop or (better) reverse global boiling?

Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Removal: A Physical Science Perspective, a peer-reviewed scientific study published in January by the American Physical Society (APS), provides an authoritative response to that question, and it isn’t encouraging.[7] Quite apart from the problems of storing captured CO2 for thousands of years, which the study doesn’t address, the scale of the problem is forbidding.

Carbon dioxide capture at oil refineries, where the gas is highly concentrated, has existed on a limited scale for decades. The CO2 is most often used for “enhanced oil recovery,” forcing still more carbon-emitting oil out of the ground.

Technologies for removing carbon dioxide from the open air, on the other hand, are new and untested. There are only a few dozen operating systems, and all are tiny, compared to the task at hand. The authors of the APS report examine a dozen proposed technologies, focusing in particular on scaling—how big can they get? While none is adequate today, three appear to have promise: direct air capture, biological carbon capture, and enhanced rock weathering.

Direct Air Capture (DAC)

DAC gets the most press. You’ve likely seen pictures of demonstration plants, with giant fans blowing air through chemical filters that absorb carbon dioxide. When the filters are saturated, the CO2 is extracted, and the chemical is reused.

The best-publicized DAC installation is the Climeworks project in Iceland, whose founder predicted that it would capture 1% of the world’s annual CO2 emissions by 2025. It has sold thousands of $250/month “carbon removal credits” each supposedly representing a quarter of a ton (250 kilograms) of captured CO2.[8] In fact, as an investigative report in the Icelandic newspaper Heimildin showed in May 2025, it has captured only 2,400 tons in total since 2021. Its own emissions are much higher than that.[9]

To be fair, the technical challenge facing DAC is enormous. A CO2 concentration of 429 parts per million is enough to significantly change the world’s climate, but in absolute terms it is a tiny fraction of the atmosphere—carbon dioxide comprises only 0.062% of the air’s weight, only 0.04% of its volume. To remove one ton of CO2, a perfectly efficient Direct Air Capture system would have to process 2,000 tons of air.[10]

As the APS report comments, if we outfitted every air conditioning unit in the world with devices enabling complete capture of all CO2 in all the air flowing through them, they would remove less than a billion tons a year.[11] Just stabilizing the global temperature would require over 15 times as much equipment; turning down the heat would require much more.

We’re told that the technology will improve over time—just look at the exponential improvements in semiconductors, for example—but DAC faces a limitation that computers don’t: the second law of thermodynamics. First stated by German physicist Rudolf Clausius in 1850, it says that all systems become more disordered over time. Entropy (disorder) increases and the only way to reverse it is by adding energy from outside. That’s not speculation—it is as solid a physical law as any ever discovered. There are no exceptions.

CO2 molecules in the air are highly disordered, scattered at random among vastly more molecules of nitrogen, oxygen and other gases. The second law of thermodynamics allows physicists to calculate, very accurately, how much energy would be needed to capture all the CO2 molecules in a given amount of air and consolidate them in one place.

The calculation applies no matter what technology is used, because we’re only measuring how much more energy there is in the consolidated output than in disordered atmospheric CO2. That’s the minimum amount of outside energy needed in a perfectly efficient process—real-world processes will require more, usually much more.

Fortunately for the equation-averse, the APS authors have done the calculation for us. Removing one ton of CO2 from the atmosphere, in a perfect system, requires 120 kilowatt hours of energy. Someone once said that the second law doesn’t tell you what you can do, it tells you what can’t be done. In this case it isn’t saying that you can capture a ton of CO2 with 120 kilowatts—it is saying that you can’t do it with less, no matter what technology you use.

Scaling up, that means that removing one billion tons a year would require a minimum of 14 billion watts of electricity, 24 hours a day, all year, which today would mostly come from CO2 emitting power plants. Realistically, less-than-perfect CDR would require three to ten times that much energy to remove one billion tons—enough to power New York City several times over, while actually adding tons of CO2 to the atmosphere.

Removing the hundreds of billions of tons actually needed to get Earth’s temperature back to preindustrial levels would require a very large fraction of the world’s energy supply—to the point where it would limit our ability to carry out other energy-hungry programs, including feeding children and combatting pandemic diseases.

For Direct Air Capture’s contribution to reducing atmospheric CO2 levels to be more than marginal, there would have to be massive improvements in DAC technology itself, and qualitative leaps in the capacity and efficiency of solar energy systems, so that every DAC installation can have its own high output zero carbon solar power plant. Since neither is likely to occur in time to prevent dangerous global warming, neither belongs in today’s climate change prevention plans.

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)

Can we get around the Second Law limit by using natural energy over a longer time? For example, there is enthusiasm in some circles about Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage, which would involve growing crops or trees, then burning them to produce electricity while capturing and burying the released CO2. Trees naturally remove atmospheric CO2 using energy from the sun (essentially a free and unlimited source), and the CO2 at the point of burning would be easier to capture because it would be highly concentrated.

Clouds of emissions pour from Drax Power Station in Yorkshire, England. (NRDC)

The world’s largest BECCS operation, the Drax Power Station in UK, says it will capture eight million tons of CO2 a year by 2030, about 3% of the UK’s annual emissions, but that is misleading. Drax doesn’t burn trees that were purpose-grown in Britain—it imports and burns wood pellets manufactured overseas, including hundreds of thousands of tons a year made from old growth forests in central British Columbia.[12] In other words, Drax is “capturing” CO2 that was already stored in some of the world’s most magnificent forests.

What’s more, the Drax plant itself is the largest CO2 emitter in Britain, pumping 12 million tons into the atmosphere every year. International carbon accounting rules give it a free pass, on the specious grounds that the forests will regrow, so their wood is a renewable fuel.

Leaving such scams aside, the physicists’ report points out that for a BECCS system that actually grows new trees, “the low efficiency of photosynthesis in converting energy to biomass … means that a lot of land would be required…. This land use would compete with existing agriculture and biodiversity efforts.”[13]

In IPCC scenarios for keeping the global temperature increase below 1.5°C that include BECCS, energy crops would occupy least 20% of all the world’s arable land by 2050, and much more if BECSS is the primary method used. Environmentalists have pointed out that such a massive change in land use would risk “compromising planetary health in areas besides climate change.”[14] At each step—planting, fertilizing, harvesting, transporting, burning and burying—BECCS is emits its own greenhouse gases. The National Resources Defense Council calculates that if current plans go ahead, by 2040 “emissions from BECCS alone are projected to surpass the U.K.’s total emissions from all other sources.”[15]

In short, BECCS will do more environmental harm than good. The European Academies’ Science Advisory Council recently told the European Union that:

“The role of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) remains associated with substantial risks and uncertainties, both over its environmental impact and ability to achieve net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. The large negative emissions capability given to BECCS in climate scenarios limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C is not supported by recent analyses …

“Deployment of BECCS at the scale in IPCC models could potentially help mitigate climate change, but at the expense of further exceeding the planetary boundaries related to biosphere integrity, land use and biogeochemical flows, while bringing freshwater use closer to its boundary…. BECCS remains associated with substantial risks and uncertainties, both over its environmental impact and ability to achieve net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere.”[16]

Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW)

In the slow carbon cycle, a key part of the Earth System’s metabolism for hundreds of millions of years, exposed rocks combine with atmospheric carbon dioxide to form stable minerals that don’t affect the climate. That weathering process naturally removes about a billion tons of CO2 a year—it is one of the factors that has kept global warming lower than total emissions could otherwise cause.

Proposals have been made to accelerate the process by grinding tons of rock into tiny particles, about one-fifth the width of an average human hair, and spreading them over large areas of land. That would greatly increase the exposed rock surfaces and—some scientists hope—greatly increase the amount of CO2 removed. Since the US and other countries already mine and transport very large quantities of ground rock for other purposes, no new technology would be needed and the energy cost would be much lower than for DAC or BECCS.

It would require a lot of land—an estimated one million square kilometers to remove a billion tons of CO2 a year—but unlike BECSS, it isn’t exclusive use. Ground rock can have fertilizing effects, so it could be spread on existing farmland, depending on local soil characteristics.

It’s important to note that the ground rock can only be used once: to keep the removal process working, billions of tons of additional rock will have to be extracted, ground, transported and spread, every year. Nothing even close to that scale has ever been done, and even if it were tried, no one knows how long removal might take, or how to measure the results.

Dead End

In October 2018, responding to a request from the UN climate conference that adopted the Paris agreement, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. The report concluded that emissions to that date were not enough to cause a 1.5°C increase, but, “lack of global cooperation, lack of governance of the required energy and land transformation, and increases in resource-intensive consumption” mean that emissions will continue, inexorably driving up the temperature.[18]

Accepting that immediate or very rapid reductions won’t happen, the authors developed a series of alternative scenarios, all of which require some use of carbon dioxide removal to make up for the failure.

Most of the scenarios assume overshoot—that the global temperature rise will exceed 1.5°C or 2.0°C for some time and must be brought down by “CDR at a speculatively large scale.” To completely prevent overshoot, the report’s Summary for Policy Makers says, CDR would have to remove between 100 and 1,000 billion tons of CO2 by 2100. Looking at the report itself, it appears that the actual requirement would likely be close to the high end of that range.

This dependence on very large scale carbon dioxide removal calls the entire scenario exercise into question. As the report admits:

“There is uncertainty in the future deployment of CCS given the limited pace of current deployment… No proposed technology is close to deployment at scale, and regulatory frameworks are not established. This limits how they can be realistically implemented. … There is substantial uncertainty about the adverse effects of large-scale CDR deployment on the environment and societal sustainable development goals.”[19]

That was in 2018. Seven years later, there are no working DAC operations, and the parallel emission reductions that the IPCC scenarios included haven’t begun and aren’t in sight. The IPCC report’s preferred option, BECSS, has lost what credibility it then had, and no one has volunteered to grind and spread rock dust.

What’s more, even if larger volumes of carbon dioxide can be captured and buried, there is no foolproof method of preventing it from leaking back into the atmosphere, either through gradual seepage or sudden disruption.[20] Another IPCC report stresses that “CO2 storage is not necessarily permanent.”

“CO2 stored in the terrestrial biosphere is subject to potential future release if, for example, there is a wildfire, change in land management practices, or climate change renders the vegetative cover unsustainable. Although the risks of CO2 loss from well-chosen geological reservoirs are very different, such risks do exist.”[21]

The danger of leaks is higher when CO2 is injected into old wells to force out the remaining oil and then left underground —not in “well-chosen geological reservoirs.” Bear in mind the oil industry’s long history of walking away from depleted wells without plugging them or monitoring ongoing leaks and emissions.

+ + + +

For fossil fuel corporations, keeping CDR on the agenda as a credible climate change solution is a Get Out of Jail Free card. Instead of stopping emissions, they promise to capture and bury them. Not now, but someday. As the CEO of Occidental Petroleum told a conference of her peers in 2023, “We believe that our direct capture technology is going to be the technology that helps to preserve our industry over time. This gives our industry a license to continue to operate for the 60, 70, 80 years that I think it’s going to be very much needed.”[22]

A few months ago, the United Nations Environment Program warned that global emissions must be cut by 42% by 2030 and 57 per cent by 2035 to keep warming under 1.5 degrees.[23] Achieving that, or anything close to it, would require an emergency action program to stop all new extraction of fossil fuels, and rapidly phase out major sources of emissions. That’s where our focus must be now, not on speculative technologies that might work one day but for now only give polluters an excuse to continue polluting.

Notes

[1] https://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu/

[2] Global Carbon Project, “Briefing on key messages Global Carbon Budget 2024,” News Release, November 13, 2024. Agriculture, land use change and cement manufacture added another 8 billion tons or so.

[3] United Nations, “Hottest July ever signals ‘era of global boiling has arrived’ says UN chief,” News Release 27 July 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/07/1139162

[4] David Archer, The Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth’s Climate, (Princeton University Press, 2016), 1.

[5] “The world is missing its lofty climate targets. Time for some realism.” Editorial, The Economist, November 3, 2022.

[6] J. Wilcox, B. Kolosz, and J. Freeman, editors, The CDR Primer, 2021, https://cdrprimer.org/

[7] Washington Taylor, Robert Rosner, Brad Marston, and Jonathan S. Wurtele, Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Removal: A Physical Science Perspective, (American Physical Society, 2025)

[8] https://climeworks.com/subscriptions-co2-removal. Consulted June 25, 2025.

[9] Bjartmar Oddur Þeyr Alexandersson and Bjartmar Oddur Þeyr Alexandersson, “Climeworks’ capture fails to cover its own emissions.” Heimildin, May 15, 2025

[10] Calculation by Aatish Bhatia in the excellent Rate of Change blog, October 28, 2020.

[11] American Physical Society, “APS Releases Report on Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Removal,” News Release, January 27, 2025.

[12] Joe Crowley, “Drax: UK power station still burning rare forest wood,” BBC, February 28, 2024.

[13] Taylor et al, Atmospheric CDR, 14.

[14] Felix Creutzig et al., “Considering sustainability thresholds for BECCS in IPCC and biodiversity assessments,” GCB Bioenergy, February 2021.

[15] Matt Williams and Elly Pepper, The BECCS Hoax, National Resources Defense Council, 2024, 4.

[16] European Academies’ Science Advisory Council, “Forest bioenergy, carbon capture and storage, and carbon dioxide removal: an update,” EASAC Commentary, February 2019, 2, 6.

[17] Helen S. Findlay et al., “Ocean Acidification: Another Planetary Boundary Crossed,” Global Change Biology, April 2025.

[18] IPCC, Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5°C (2018), 95.

[19] Ibid, 158.

[20] It has been suggested that CO2 buried in ultramafic rock would form solid carbonate minerals that can’t escape. That’s encouraging, but it hasn’t gone beyond small tests.

[21] IPCC, Special Report: Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage (2005), 373

[22] Quoted in Corbin Hiar, “Oil companies want to remove carbon from the air — using taxpayer dollars,” E&E News, July 13, 2023.

[23] United Nations, ‘Climate crunch time is here,’ new UN report warns, News Release, October 24, 2024.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2025/0 ... e-climate/