The Turtle Island Liberation Front Warning for Activists

Margaret Kimberley, BAR Executive Editor and Senior Columnist 17 Dec 2025

Attorney General Pam Bondi and FBI Director Kash Patel appear at a news conference at the Justice Department on Dec. 4 in Washington. (Alex Brandon / Associated Press)

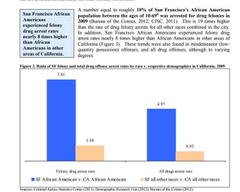

Arrests of members of the Turtle Island Liberation Front are the latest in a decades-long effort to criminalize the left and to make examples of anyone who might fit the profile of being a “designated terrorist.”

The United States has a long history of using informants and entrapment as tools to discredit or to defeat leftist movements. There are other objectives as well, as Black Agenda Report explained in 2010, “The object is to terrify the public into surrendering their civil liberties in a twilight struggle with a mostly nonexistent domestic enemy.” It is important to remember the many examples of state repression as we learn of the arrest of members of a little-known and newly formed organization called the Turtle Island Liberation Front, who stand accused of planning New Year's Eve bombings in Southern California. It is an understatement to say that the charges against them should not be accepted at face value.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has traditionally used paid informants to undermine movements or even to justify its existence by convincing the public they are in danger of terrorist attacks with high-profile cases that they and their informants create out of whole cloth. There were many such instances in the years after the September 11 attacks, and two of the most infamous were those of the “Newburgh Four” and the “Liberty City Seven.” In both cases, paid informants entrapped Black men who actually had no discernible political activity or ideology. In the 2009 case of the Newburgh Four, they were charged with planning to blow up a Bronx, New York synagogue in a plot that was hatched entirely by the FBI informant. They stated they never intended to carry out the deed, but merely hoped to be paid for doing nothing at all. In 2023, a federal judge ordered compassionate release for three of the four men, describing them as “... hapless, easily manipulated and penurious petty criminals." A fourth defendant was released in 2024, and the judge added that he and the others were victims of an “FBI-orchestrated conspiracy.”

In Florida, the Liberty City Seven also fell under the sway of an informant in 2006, but two juries were deadlocked before a third convicted them, under circumstances similar to those of the Newburgh Four. The thinness of the case was revealed by Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and the FBI Deputy Director when they took questions at the press conference announcing the arrests.

“Question: Did any of the men have any actual contact with any members of al-Qaeda that you know of?

Attorney-General: The answer to that is "No".

Question: Did they have any means to carry out this plot? I mean, did you find any explosives, weapons?

Attorney-General: You raise a good point ... We took action when we had enough evidence.

Question: Was there anything against the Sears Tower other than this one apparent, just, kind of mention of the Sears Tower? It doesn't look like they ever took pictures or ...

Deputy Director of the FBI: One of the individuals was familiar with the Sears Tower, had worked in Chicago, and was familiar with the tower. But in terms of the plans, it was more aspirational than operational.”

Despite the obviously flimsy case, the men were convicted and were freed after serving their sentences, which ranged from six to thirteen years.

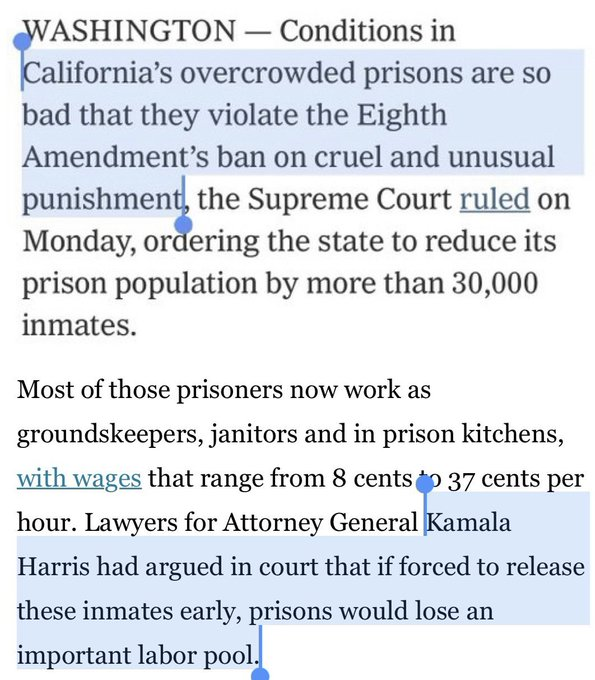

Donald Trump has spoken of an “enemy within” and of what he calls domestic threats. He wants to frighten anyone who might oppose his policies into silence by threatening them with legal action. His definition of what makes a person or group a terrorist is quite broad and may serve to criminalize any opposition that he chooses.

Attorney General Pam Bondi’s leaked December 4 memo, “Countering Domestic Terrorism and Organized Political Violence,” lays out how the Trump administration defines a group or individual as being domestic terrorist. “These domestic terrorists use violence or the threat of violence to advance political and social agendas, including opposition to law and immigration enforcement; extreme views in favor of mass migration and open borders; adherence to radical gender ideology, anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, or anti-Christianity; support for the overthrow of the United States Government; hostility towards traditional views on family, religion, and morality; and an elevation of violence to achieve policy outcomes, such as political assassinations.”

Political assassinations, like any murder, are illegal, and so is overthrowing the government. But mostly, Bondi has produced a list of rights that are allegedly protected by the First Amendment. We are told that we have the right to hold the opinions of our choice regarding law enforcement, and we have the right to oppose capitalism or Christianity or any other religion. As for “anti-Americanism,” we can also have any opinion we want about this country or its government. Trump wants obedience and has created a definition of domestic terrorism that applies to millions of people in this country.

But there are many people who cannot be fooled so easily and arresting members of the Turtle Island Liberation Front would only be acceptable to the public if they were charged with a crime. The FBI made sure of that with the help of a paid informant and an undercover FBI agent. It isn’t clear when or how the informant and the agent came into contact with the group and that vagueness is a key issue in determining whether the accused can claim to have been entrapped. But the bar for that claim is high and even if the informant and the agent suggested making bombs, the suspects may still be convicted.

Activist groups must always be on alert and must assume that any member, whether new or old, who suggests committing an illegal act is an informant being paid to get them arrested. It has always been true that the state, whether under Trump or another president, wants to shut down leftists or use marginalized people to justify the continued existence of law enforcement and a carceral state.

The existence of informants and turncoat snitches can make organizing difficult and activists are often paranoid about the wrong things, which serves the goals of the FBI. Those goals have changed little since the worst days of COINTELPRO. Perhaps Trump will revive the idea of the Black Identity Extremist or some other such designation. The Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) was used against the Uhuru Three and can be used against anyone who has contact with individuals or groups abroad.

In recent congressional testimony, General Gregory Guillot, commander of the U.S. Northern Command, was asked if he would target any domestic “designated terror organizations.” He replied, “If I had questions, I would elevate that to the chairman and the secretary. … And if I had no concerns and I was confident in the lawful order, I would definitely execute that order.”

That statement is shocking, but perhaps it should not be. The military, FBI, and local police can and do target anyone they want. Seemingly innocuous activity can make one a target. But forewarned is forearmed and people in movement spaces would do well to keep this history top of mind.

https://blackagendareport.com/turtle-is ... -activists

*****

JOHN KIRIAKOU: US Prison Horror Show Plays On

December 16, 2025

A year into President Trump’s second term in office, hopes for inmates across the country have dimmed. Deadly abuses have continued in full swing.

President Donald Trump taking questions from the press aboard Air Force One en route to Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania, on Dec. 9. (White House / Molly Riley)

By John Kiriakou

Special to Consortium News

CN at 30

Hopes for a major restructuring of the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) a year into President Donald Trump’s second term in office have come to naught.

Trump in June named former federal prisoner Josh Smith as the BOP’s deputy director. It was a bold and, in my view, progressive move. While greeted with hostility from the union representing federal corrections officers, it inspired hope among the tens of thousands of prisoners in federal custody.

Many of us thought that the next step would be something equally bold — perhaps to turn away from private prisons, which have cost the government millions of dollars in lawsuits because of wrongful deaths in custody, or perhaps to institute programming that would better prepare prisoners for release and for reintegration into society. But none of that has happened. And it’s unlikely that it will.

Joshua J. Smith, deputy director, Federal Bureau of Prisons. (BOP)

The problem is that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Sure, Josh Smith as deputy director of the BOP is a great idea. He spent five years in a federal prison following a drug conviction before founding a non-governmental organization that helps newly-released prisoners, and he brings a perspective that the BOP has never had before — from a former prisoner.

But that hasn’t changed any of the day-to-day problems that the BOP has experienced for decades. A small sampling of recent events includes:

In Virginia — a state that has long been known for its broad disregard for the rights of prisoners at the federal, state and local levels — an ongoing collection of at least five federal lawsuits paints a picture of senseless violence against prisoners and petty retaliation by BOP officials.

Multiple prisoners at the U.S. Penitentiary (USP) Lee have alleged that guards beat them unprovoked over a period of years, in several cases while in shackles, leading to broken bones, ruptured organs, and mental breakdowns. Guards also wrongly accused one trans female prisoner of being a child molester so that other prisoners would beat her.

Across the country at the deeply troubled Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) at Dublin, California, which is now closed, at least 22 female prisoners were granted compassionate release after at least 100 were repeatedly sexually assaulted by as many as 10 prison employees, including the facility’s warden, assistant warden, chaplain, and doctor, all of whom are now incarcerated.

Rather than address the culture in which senior BOP employees believed that it was appropriate to rape prisoners at will, something that became known as the “rape club,” the BOP elected to simply shut the place down and transfer the prisoners to other prisons.

In July, a BOP guard received an eight-year prison sentence for raping three prisoners at the federal detention center in Honolulu. Mikael Rivera received a sentence longer than he otherwise would have because he elected to abscond while out on bond. He was recaptured after a three-day manhunt.

Federal Detention Center, Honolulu as seen from Honolulu International Airport, 2017. (293.xx.xxx.xx/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0)

These events haven’t taken place in a vacuum. State and local department of corrections and county jails have watched as the federal courts have turned a blind eye toward BOP wrongdoing.

If there’s no downside to doing literally anything you want to do to a prisoner and get away with it, then why stop? That attitude has led to more horrors at the state and local levels:

The state of Minnesota was forced to pay the family of a hemophiliac prisoner, Dillon Bakke, $3.6 million after he died three days into a brain bleed, which the prison refused to treat. The prison also refused to allow Bakke to take his hemophilia medication.

Bakke had complained repeatedly of severe head pain, an inability to walk or stand and severe nausea. He was finally allowed to go to the jail’s medical unit, where he died 12 hours later. The 32-year-old was being held on a charge of “suspicion of drug possession.”

California’s attorney general is suing Los Angeles County and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office, alleging that the county’s jails are “inhumane” and that the sheriff has failed to improve conditions, despite the courts repeatedly demanding that he do so. The L.A. County Central Jail is designed to hold 3,509 people, but averages 4,632 on any given day.

Satellite jails are even more overcrowded, and independent inspectors have documented the widespread presence in all the facilities of feces, sewage, vermin, fire hazards, mold and stale air. The sheriff contends that “the situation is improving and the attorney general’s lawsuit is based on outdated information.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department conducting a traffic stop in West Hollywood, 2021. (Chris Yarzab /Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY 2.0)

The tiny town of Issaquah, Washington, was forced to pay the families of two prisoners $5.5 million after 43-year-old Kevin Wiley and 48-year-old David McGrath died from “acute combined drug intoxication.” The men didn’t take drugs while incarcerated. They died while withdrawing from fentanyl and methamphetamine intoxication, having been refused any medical help.

Prison officials did nothing over the course of three days in the two separate cases, while watching the men vomit, convulse and beg for help. Wiley asked to see a nurse, but his request was never answered.

Three women held in Kansas’ Sedgwick County Detention Center split a $375,000 settlement after being raped by a guard. The guard, 22-year-old Dustin Burnett, had been thrown out of the military for possessing child pornography before being hired as a guard by the Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Office.

The Ohio attorney general has appointed a special prosecutor to investigate how and why a female double amputee died while being restrained in a jail medical unit. Tasha Grant, 39, had no legs, but was nonetheless strapped down to a medical unit bed. She began experiencing chest pains, but was ignored and died shortly thereafter.

When asked why a double amputee was restrained in such a way, a prison spokesman said disingenuously, “She threw herself on the floor and wouldn’t cooperate.” The spokesman apparently hadn’t been told that Grant was unconscious at the time.

I supposed that it’s not exactly true that Donald Trump hasn’t done anything with the BOP since naming Josh Smith as its deputy director.

On Sept. 25, the president abolished collective bargaining rights for the corrections officers’ union and he canceled their union contract. BOP Director William K. Marshall III said in an email to all BOP employees, “The whole purpose of ending this contract is to make your lives better.”

I wouldn’t hold my breath.

https://consortiumnews.com/2025/12/16/j ... -plays-on/