Harpal Brar

Wednesday 1 January 2025

Contrary to the myths peddled by Khrushchev and Trotsky and repeated endlessly by anticommunist historians, Josef Stalin was a selfless, modest and devoted revolutionary, and a lifelong student of Marxist-Leninist science.

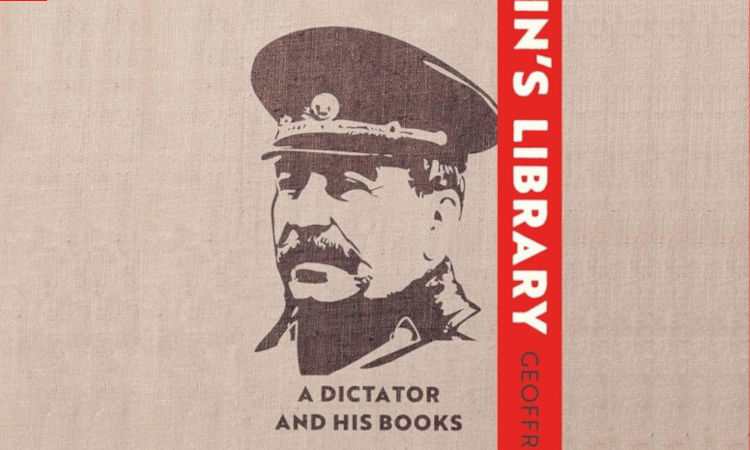

Over the next few issues of Lalkar we shall be publishing this review of Geoffrey Roberts’ book on Stalin’s library. Although as a bourgeois academic Roberts is obliged to take an anticommunist approach and to repeat many of the usual slanders against Stalin, such as in the sentence: “This book explores the intellectual life and biography of one of history’s bloodiest dictators, Josef Stalin” (Introduction, p2), nevertheless, as an honest historian, he has been able to shed a bright light on Stalin as a person, showcasing not only his genius as a political leader but also his untiring and meticulous devotion to the cause of proletarian revolution and the wellbeing of the toiling masses.

*****

By the time of his death, Josef Stalin’s library contained 25,000 books, periodicals and pamphlets. Of these, the 400 books that he had marked and annotated “revealed that Stalin was a serious intellectual who valued ideas as much as power”, who read to “acquire a higher communist consciousness, seen as central to the … goals of Soviet socialism. An ideologue as well as an intellectual, Stalin’s professed belief in Marxism-Leninism was wholly authentic, as can be seen from his library.”

“Lenin was his favourite author,” but he also read Leon Trotsky and “other arch-enemies”. He was, says Roberts, “an emotionally intelligent and feeling intellectual”, whose dedication to “Lenin’s memory was unabated”. (Roberts, pp2-3)

Nikita Khrushchev, in his notorious 20th party congress speech (often called the ‘secret speech’), asserted that Stalin embellished his official biography to inflate his sense of self-importance. Roberts refutes this lie, stating that Stalin “toned down the adulation. Even more striking was the way he reduced his personal presence in the [book the] … History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1938)”, though his contribution was “detailed enough for him to be considered a de facto co-author”. (p4)

In the opening chapter of Chapter 1 entitled ‘Bloody tyrant and bookworm’, Roberts, having associated himself with the hackneyed assertions bout Stalin being a “bloody tyrant, a machine politician, a paranoid personality, a heartless bureaucrat, and an ideological fanatic”, goes on to say that Stalin was “an intellectual .., a dedicated idealist and an activist intellectual”, who was a voracious reader, “reading for the revolution to the very end of his life”.

While he hated “the bourgeoisie, kulaks, capitalists, imperialists, reactionaries, counter-revolutionaries, traitors – he detested their ideas even more”. (p6)

He had absolutely no “compassion or sympathy for those he deemed enemies of the revolution”. (p7)

A voracious reader, he read a lot of left-wing literature, especially works by Karl Marx, Frederick Engels and Vladimir Lenin. In addition, he devoured the classics of Russian literature and western fiction – from Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Schiller, Heine, Hugo, Thackeray and Balzac. He also read works by deadly enemies such as Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kautsky and Bukharin. In the 1930s, he devoted much attention to reading Soviet literature.

The history of revolutionary movements abroad was of great interest to him, and he often gave strategic and tactical advice to visiting foreign communists. “Military strategy was an enduring interest,” reading the works “of the foremost French, German, Russian and Soviet strategic theorists. Not surprisingly, this interest became paramount during the second world war, when he became the Soviet Union’s supreme commander. Stalin was also attracted to the history of the ancient world, especially the rise and fall of the Roman empire.” (p9)

In addition, he spent considerable time reading about science, linguistics, philosophy and political economy, making notable interventions in debates about genetics, socialist economics and linguistic theory.

Such was Stalin’s reverence for books that, at a gathering of Soviet writers attending a national congress in August 1934, he said: “To build socialism we need civil, electrical and mechanical engineers. We need them to build houses, automobiles and tractors. But no less important, we need engineers of the human soul, writers – engineers building the human spirit.” (p11)

Beginning with Lenin, the Bolsheviks always laid stress on Soviet power, rapid industrialisation, with an emphasis on the development of heavy industry, mass literacy and cultural enlightenment – for an illiterate person stands outside of politics.

To realise Lenin’s vision, the Bolshevik government created a vast network of libraries, reading rooms and mobile units that secured a supply of books and revolutionary literature to within a ten-minute walk of every person’s home. Libraries were to provide a quick and free service, with long opening hours, easy borrowing facilities and inter-library loans.

During the Great Patriotic War, the Nazis destroyed 4,000 libraries, but by the end of the war there were still 80,000 left in the USSR, with 1,500 in Moscow alone.

The Bolsheviks were keen on persuading the masses to read classics of fiction – both Russian and foreign – and managed to have the classics of world literature translated into Russian.

The reaction of Jonathan Brent (a Yale University press editor) to an encounter with the surviving books in Stalin’s library in the 2000s “verged on the religious”. On being shown some of Stalin’s annotated works, he expressed himself thus:

“Nobody was prepared for what we found … To see the works in his library is somehow to be brought face to face with Stalin. To see the words his eyes saw. To touch the pages he touched and smelled. The marks he made on them trace the marks he made on the Russian nation … Not a single work I inspected was not read by him. Not a single work was not copiously annotated, underlined, argued with, appreciated, disdained, studied … We see him thinking, reacting, imagining in private.” (p15)

Allegations of paranoia

It is typical of bourgeois histiography that it ascribes paranoia to the Soviet leadership and goes on to give the most stupid explanation for this alleged paranoia: “the politics and ideology of class war in defence of the revolution and in pursuit of communist Utopia”. (p16)

In support of this mindless assertion, Roberts cites the even more stupid assertion of Stephen Kotkin: “The problems of the revolution brought out the paranoia in Stalin, and Stalin brought out the paranoia in the revolution.” (p16)

In other words, if you do not want to suffer from paranoia, don’t attempt a proletarian revolution and the class struggle it entails. What bourgeois scholars characterise as paranoia is merely the vigilance of the proletarian state and its leadership to guard against real, not imaginary, aggression, sabotage, spying and campaigns of murderous activity. In fact, we would be justified in criticising a socialist state if it did not protect itself against such activities; if it did not exercise revolutionary violence to suppress every act of counter-revolutionary activity from sources internal as well as external.

If that annoys the flunkeys of imperialism and causes them to accuse proletarian leaders of paranoia, the latter can laugh off such criticism as the ravings of frustrated counter-revolutionaries.

Following Lenin’s teaching, Stalin emphasised that the class struggle intensifies under socialism; that the stronger the USSR became, the more it would drive the bourgeoisie to desperation in an attempt to crush the revolution through a combination of foreign aggression and internal sabotage and subversion. This reality obliged the Soviet state to adopt hash measures to thwart attempts at the overthrow of the proletarian state – not any paranoia on the part of the Soviet leadership.

“There was no one whose books he [Stalin] read more assiduously and admiringly that those of Lenin.” (p16)

Stalin’s biography

“Lenin is my teacher, he said repeatedly and proudly.

“‘The most important thing is the knowledge of Marxism,’ he scribbled in the margin of an obscure military theoretical journal in the 1940s. He meant it: In the thousands upon thousands of annotated pages in Stalin’s library, there is not a single hint that he harboured any reservations about the communist cause. The energy and enthusiasm he applied to annotating arcane points of Marxist philosophy and economics is eloquent – and sometimes mind-numbing – testimony to his belief that communism was the way, the truth and the future.”

All the same, “the vehemence with which he viewed his political opponents never prevented him from paying careful attention to what they wrote”. (pp16-7)

“Stalin kept no diary, wrote no memoirs and evinced little interest in his personal being,” yet in answer to persistent questions from foreign visitors, he occasionally gave answers that gave a small glimpse of his early life. Visiting Stalin in 1931, Emile Ludwig, a German writer who had authored biographies of some famous people, asked Stalin what made a rebel – was it perhaps that he was treated badly by his parents? Here is Stalin’s answer:

“‘No. My parents were uneducated people, but they did not treat me badly by any means. It was different in the theological seminary of which I was then a student. In protest against the humiliating regime and the Jesuitical methods that prevailed in the seminary, I was ready to become, and eventually did become, a revolutionary, a believer in Marxism as the only genuinely revolutionary doctrine.’” (p18)

In 1939, the Soviet dramatist Mikhail Bulgakov was keen to write a play about Stalin’s youth, and to stage it in connection with celebrations of Stalin’s 60th birthday. Stalin vetoed the project with the modest remark that “all young people are alike, why write a play about the young Stalin?” (p19)

As Stalin showed not the slightest interest in harping on about his childhood, family life, personal relations and youthful traits, the gap thus left has been filled by gossip, speculation, “stereotyping and cherry-picking of partisan memoirs to suit the grinding of many different personal and political axes. ‘When it comes to Stalin,’ writes the foremost biographer of his early life, Ronald Suny, ‘gossip is reported as fact; legend provides meaning; and scholarship gives way to sensationalist popular literature with tangential reference to reliable sources.’”

Like many Bolsheviks, Stalin was a firm believer in self-effacement. He lived his life in and through the collective that was the party. His individual and private life was strictly subordinate to his political life.

Visiting Georgia for a month-long trip in 1936, Stalin gave a speech to railway workers in Tbilisi in which he summed up his political journey. It was the closest he ever came to writing an autobiography. Replying to the flattering greetings of the workers, he disabused them of the notion that he was the “legendary warrior-knight that they conceived him to be. The true story of his life, he said, was that he had been educated by the proletariat, his first teachers being the Tbilisi workers who came in touch with him when he was put in charge of a study circle of railwaymen in 1898; and from them he received lessons in practical political work: this was his ‘first baptism in the revolutionary struggle’, when he served as an ‘apprentice in the art of revolution’.

“His ‘second baptism in the revolutionary struggle’ was the years (1907-9) he spent in Baku organising the oil workers. It was in Baku that he became a journeyman in the art of revolution. After a period in the wilderness – ‘wandering from one prison or place of exile to another’, he was sent by the party to Petrograd in 1917 where he received his ‘third baptism in the art of revolutionary struggle’. It was in Russia, under the guidance of Lenin, that he became a ‘master workman in the art of revolution’.”

When Yaroslavsky, a senior party official wanted to publish a biography of Stalin, the latter gave him short shrift, saying: “I am against the idea of a biography about me.”

The absence of an official biography was a gap in a vista “that Stalin himself had opened up in 1931, when he published a letter on ‘some questions concerning the history of Bolshevism’ in the journal Proletarskays Revolyutsia. In it, he severely criticised Anatoly Slutsky, who had published an article in the same journal that criticised Lenin’s policy towards German social democracy before the first world war. Stalin denounced the author of this article as an ‘anti-party and semi-Trotskyist’ … [and] his criticisms were supported by a textual and historical analysis of the question concerned.” (p23)

Slutsky’s article became the occasion for Stalin to criticise the writings of certain party historians, Yaroslavsky included: “Who, except hopeless bureaucrats, can rely on written documents alone? Who, except archive rats, does not understand that a party and its leaders must be tested primarily by their deeds ..? Lenin taught us to test revolutionary parties, trends and leaders not by their declarations and resolutions but by their deeds.”

Although written to counter Slutsky’s outrageous assertions about Lenin, Stalin’s article served to increase the demand for an autobiography of Stalin.

The gap created by the absence of an authorised biography of Stalin was filled by two publications. The first was a book-size lecture delivered by Lavrenti Beria and the second by a semi-official popular biography by the French communist intellectual Henri Barbusse (1873-1935).

Before becoming security chief in 1938, Beria headed the Georgian Communist party. Beria’s lecture on the history of Bolshevik organisation in Transcaucasia, delivered in July 1935, was serialised in the Bolshevik paper and then published as a book. Beria sent an inscribed copy to his “Dear, beloved teacher, the Great Stalin”. The book soon became a “classic … issued in eight separate editions and remained in print until Stalin’s death in 1953”. (p24)

Barbusse was a famous writer who had been a member of the French Communist party since 1923; he had helped to organise the 1932 Amsterdam World Congress Against War and was head of the World Committee Against War and Fascism in 1933. Stalin met with Barbusse on four occasions between September 1927 and November 1934. “I am not so busy that I can’t find time to talk to Comrade Barbusse,” Stalin remarked at their meeting in 1932. (Roberts, p25)

It was the fame of Barbusse as a writer and a reliable communist that persuaded Stalin to accept the proposal.

The book was published in the USSR and France, as well as some other countries. It was published in French in 1935 and in Russian in 1936. Sadly, by the time of its publication in Russian, Barbusse was no more, having passed away during a trip to Moscow in 1935.

His memorial meeting in Moscow was packed with Soviet intellectuals and party functionaries, and an honour guard escorted the mortal remains of Barbusse to the railway station. An official delegation accompanied them to Paris on the Siberian Express. Stalin issued a brief statement: “I share pain with you, on this occasion of the passing of our friend, the friend of the French working class, the noble son of the French people, the friend of workers of all countries.” (p26)

At the time of his death, Barbusse was working on a screenplay of Stalin’s life.

Barbusse’s aim in writing the book was “to provide a complete portrait of the man on whom this social transformation pivots so that a reader may get to know him”.

To this end, he had written a very brief history of revolutionary Russia in which Stalin, together with Lenin, is the main character, an in-depth contrasting portrait of the personalities of Stalin and Trotsky. The latter is depicted as arrogant, self-important, fractious, verbose and despotic, while Stalin “relies with all his weight upon reason and practical common sense. He is impeccably and inexorably methodical.

“He knows. He thoroughly understands Leninism … He does not try to show off and is not worried by a desire to be original. He merely tries to do everything that he can do. He does not believe in eloquence of sensationalism. When he speaks he merely tries to combine simplicity with clearness.” (Stalin: A New World Seen Through One Man, 1935, pp175-6; Roberts, p26)

Barbusse’s conclusion was that, by the time of the assassination of Sergei Kirov (the Leningrad party leader), Trotsky had become a counter-revolutionary. His account of Trotsky’s path to counter-revolution, his disputes with Lenin and Stalin, are accurate and convincing.

It has been suggested that Barbusse’s biography may have provided a template for the Soviet short biography of Stalin. Both books emphasise Stalin’s affection for Lenin, his heroic work in the revolutionary and civil war periods; in both Stalin is described as the worthy continuer of the cause of Lenin – “the Lenin of today”; both have references to Stalin’s omnipresence and omniscience; both books praise Stalin in grandiose terms.

Notwithstanding these few biographies, “Stalin remained resistant to biographies or the hagiographies of himself, because he did not want to give too much encouragement to his personality cult, ‘which is harmful and incompatible with the spirit of our party’, as he told the Society of Old Bolsheviks which wanted to stage an exhibition based on his biography.” (p27)

He also forbade the publication of a Ukrainian party brochure about his life. He was particularly opposed to the publication of accounts of his childhood. Most noteworthy was his intervention to stop the publication in 1938 of a children’s book by V Smirnova called Tales of Stalin’s Childhood: “The little book is a mass of factual errors, distortions, exaggerations and undeserved praise. The author has been misled by fairy-tale enthusiasts, liars (perhaps ‘honest’ liars) … Most important is that the book has a tendency to inculcate in the consciousness of Soviet children (and people in general) a cult of personalities, great leaders and infallible heroes. That is dangerous and harmful … I advise you to burn the book.” (p28)

Stalin was committed to historical truth. When Mikhail Moskalev (1902-65) wrote a feature article ‘JV Stalin at the head of Baku Bolsheviks and workers, 1908’ and published it in a historical journal in 1940 (which was then summarised by a feature article in Pravda), Stalin complained to Yaroslavsky, the editor of the journal, that the article distorted historical truth and contained factual errors. He sent copies of his letter marked ‘not for publication’ to the politburo and to the editor of Pravda. He criticised Moskalev’s use of dubious memoir sources and concluded that “The history of Bolshevism must not be distorted – that is intolerable; it contradicts the profession and dignity of Bolshevik historians.” (p28)

In a letter to Stalin, Yaroslavsky set out the sources on which Moskalev’s article was based. Two days later, on 29 April, Stalin replied, repeating his objections and pointing out the unreliability of Moskalev’s sources, adding that “An historian has no right to just take on trust memoirs and articles based on them. They have a duty to examine them critically and to verify them on the basis of objective information.” The party leadership, he went on to emphasise, needed a scientific history, one based on the whole truth: “Toadyism is incompatible with scientific history.” (p28)

Stalin contradicted Moskalev’s statement that he (Stalin) had been the editor of the Baku workers’ newspaper Gudok (The Siren), saying: “I never visited the Gudok editorial offices. I was not a member of the editorial board. I was not the de facto editor of Gudok (I didn’t have the time).”

In the light of the above information, it is not difficult to conclude that assertions made by bourgeois falsifiers of history, including the Trotskyites and the Khrushchevite revisionists, about Stalin promoting the cult of his personality are nothing but slanderous fabrications and a pack of lies. The real Stalin was a modest, humble and self-effacing man who attributed every achievement of the Soviet Union to Lenin, whose pupil he claimed to be all his life.

Publication of Stalin’s works

A project truly close to Stalin’s heart was the publication of his collected writing, articles, letters, speeches, statements, reports, interviews and contributions to Marxist theory – which doubtless furnish a great deal of material that charts his political journey and its milestones, recording as they do his most important thoughts.

The question of publishing these was raised in December 1939 on his 60th birthday. However, for various reasons the project kept on being delayed, and Stalin showed no inclination to hurry the process along. Finally the first volume of his works (Sochineniia) saw its publication in 1946.

As to the size of the print run, in his characteristic modesty he suggested that 30,000 to 40,000 copies would be sufficient. When someone pointed out that the print run for Lenin’s collected works was half a million, he replied curtly that he was no Lenin. In the end, he was persuaded to accept a figure of 300,000.

Stalin wrote a brief preface to the first volume in which he admitted his own mistakes and asked to readers to regard his early writings as the work “of a young Marxist not yet moulded into a finished Marxist-Leninist”. His two mistakes, he said, were: first, that he accepted the then prevailing view that the socialist revolution should only take place in a country where the proletariat was the majority of the population, while Lenin had shown that the victory of socialism wad possible even in a predominantly peasant country like Russia; and secondly, that he had been wrong in advocating the handover of the landlords’ land to the peasants as their private property, rather than taking it into state ownership as favoured by Lenin.

Between 1946 and 1949, 13 volumes of his works were published. Their publication stalled and the project was cancelled by Khrushchev following his scandalous denunciation of Stalin at the 20th party congress in 1956.

Meanwhile, even before the publication of the 13 volumes, many of Stalin’s writings such as The Foundations of Leninism, Problems of Leninism, Marxism and the National Question, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks), and his wartime speeches had been published and circulated in millions of copies. The History of the Communist Party was to have been Volume 15 of his works, having been acknowledged that it was his work, not that of an anonymous party commission.

Roberts has this concluding observation on the 13 volumes published during his life:

“Their limitations notwithstanding, the 13 published volumes of Stalin’s sochineniia were destined to become the single most important source for his biography – ‘fundamental’ to ‘the study of the man and his age’, as McNeal puts it. They have been particularly important for those biographers who see Stalin as he saw himself – primarily a political activist and theorist, whose driving force was his unstinting commitment to the communist ideology that shaped his personality as well as his behaviour.” (p35)

One of Khrushchev’s assertions was that Stalin edited the second, postwar, edition of his Short biography because it contained insufficient praise of him. Roberts debunks that claim saying that “he actually toned down the adulation and insisted that other revolutionaries should be accorded more prominence. The same was true of many other texts that Stalin edited.”

Stalin, the ‘bookworm’

From very early on, Stalin was a “bookworm” and an “autodidact”. “Books were his inseparable friends; he would not part with them even at meal times,” according to one of his schoolmates. (p39)

By all accounts he was a bright student. In 1894 he matriculated and, on the basis of his results, was recommended for entry into a seminary. At the same time, he took his first step to a revolutionary future after visiting a radical bookshop, then only recently opened in Gori, in whose reading room he found alternative literature to that prescribed by his school.

At the age of 15 he moved to the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, to enter Spiritual Seminary, which, like his school, was run by the Georgian branch of the Russian Orthodox Church. It was a seminary reserved for bright boys destined for the priesthood. He sailed through the entrance exam and was awarded a place. By the time Stalin arrived at the seminary, there was a well-established tradition of student protest and intellectual rebellion, especially against the school’s russification policies and attempts at suppression of the Georgian language.

In 1896-7, he joined a secret study group organised by an older seminarian, Seit Devdariani, which included in its curriculum, among others, the works of Marx and Engels.

A source of forbidden secular literature was the Georgian Literary Society’s ‘cheap library’, which was run by the editor of Iveria, Ilya Chavchavadze. Stalin’s reading habits were discovered by the seminary inspector, who confiscated his copy of Victor Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea, in which he found the said library ticket. As a punishment, Stalin was confined to a cell for a prolonged period. The principal noted that Stalin had already been warned about the possession of Hugo’s book on the French Revolution – Ninety-three.

On thirteen occasions he had been found to be reading books borrowed from the Cheap Library. At the time, his favourite author was the Georgian Alexander Qazbegi, whose fictional hero Koba was an outlaw who resisted Russian rule in Georgia. Stalin adopted that as his first pseudonym upon joining the illegal revolutionary underground. Only in 1913 did he adopt the name Stalin – the ‘Man of Steel’.

He led the Marxist study circles in his third and fourth years at the seminary, a subversive activity that led him to join the Russian Social-Democratic Labour party (RSDLP) in 1898 and to his expulsion from the seminary in 1899.

As he had failed to graduate, he could neither become a priest nor go to university, although he was qualified to teach in a church school. Instead, he secured a job at the Tbilisi meteorological observatory, on whose premises he lived and kept a record of instrument readings. This was his first and last normal job.

He continued his study of radical literature and extended the scope of his political involvement. A key influence at this juncture was Lado Ketskhoveli, who became a conduit for his connection to both the underground revolutionary movement and workers’ study circles. According to Roberts, “An intellectual as well as an activist, Lado was Stalin’s first political role model.” (p42)

On religion

Notwithstanding his educational background, when it came to religion, Stalin was a “model of Bolshevik orthodoxy”. (p42)

On leaving the seminary, Stalin turned his back on religion and became an atheist, an ardent opponent of clericalism and of supernatural thinking. While espousing religious freedom, the Bolsheviks reserved the right to campaign against religion. In Stalin’s words, written in 1906:

“Social democrats will combat all forms of religious superstition … will always protest against the persecution of Catholicism or Protestantism; they will always defend the right of nations to profess any religion they please; but at the same time … they will carry on agitation against Catholicism, Protestantism and the religion of the Orthodox Church in order to achieve the triumph of the socialist world outlook.” (p43)

On coming to power, the Bolsheviks separated the church from the state and schools from the church. Freedom of religion was guaranteed by the constitution adopted in 1918, as was the right to anti-religious propaganda. In 1922, church valuables were expropriated.

Stalin explained to a visiting American delegation in 1927 that, while the Communist party stood for religious freedom, it “cannot be neutral towards religion, and it conducts anti-religious propaganda against all religious prejudices because it stands for science … because all religion is the antithesis of science”. He added: “Have we repressed the clergy? Yes, we have. The only unfortunate thing is that they have not yet been completely eliminated.” (Collected Works, Vol 10, pp138-9)

In November 1920, in a speech to the Baku Soviet on the third anniversary of the October Revolution, Stalin said:

“Here I stand on the border between the old capitalist world and the new socialist world. Here, on this border line, I unite the efforts of the proletarians of the west and the peasants of the east in order to shatter the old world. May the god of history be my aid.” (Collected Works, Vol 4, p406)

The last sentence in the above quotation has been interpreted by some bourgeois historians as proof of Stalin’s continuing religiosity. That is utter nonsense. Plenty of such references can be found in the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin, but it has not occurred to anyone to attribute religious piety to them. Language lags behind practice and even thought. It will be quite some time before expressions such as ‘Thank God’ or ‘For God’s sake’ fall out of use.

The Bolshevik

Quite early on in his revolutionary life, the party he belonged to – the RSDLP – split into two factions. Stalin sided with the Bolshevik faction headed by Lenin. The original split was over the conditions (rules) of party membership. While the Mensheviks, headed by Martov, advanced an open party engaged in legal activity, the Bolsheviks argued for a disciplined, highly centralised, underground party, which alone could hope to succeed in the conditions of illegality and tsarist repression.

While the Mensheviks viewed socialist consciousness through the experience of everyday struggles of the working class to improve wages and conditions at work, the Bolsheviks asserted that everyday struggles could only produce trade unionist consciousness; socialist consciousness, on the other hand, had to be transmitted by the socialists to the strikers.

Whereas the Mensheviks thought of the socialist revolution as some distant occurrence, the Bolsheviks believed it would occur sooner through an alliance of the proletariat and the poor peasantry. Stalin could have found favour with the Mensheviks, who were quite strong in Georgia, but he chose to join the Bolsheviks because he genuinely subscribed to the policy, tactics and strategy advanced by Lenin’s Bolsheviks.

Roberts correctly says that Stalin’s biographers have “tended to neglect the niceties of politics, day-to-day struggles, factions and personalities of the Russian revolutionary underground. Yet this constituted nearly half of his adult life. This was the political and social environment in which his character and personality was formed. As a young revolutionary Stalin adopted beliefs, acquired attitudes, underwent experiences and made choices.”

He added: “There is no shortage of evidence about the life of young Stalin. The problem is that much of it consists of highly partisan and biased memoirs, very little of his primary personal documentation from this early period having survived. Typically, how nationalists recall Stalin correlates with how they see and judge his later life.” (p49)

All the same, writes Roberts: “As a young man, Stalin was confident and self-assured. He was a faithful member of Lenin’s Bolshevik faction. He was loyal to his comrades and contemptuous of political opponents … he was a skilled polemicist in print. His personal life was strictly subordinate to his all-consuming political passions. Much of Stalin’s youthful political style derived from that of his master and political exemplar, Lenin”. (p49)

As he was never the emigré revolutionary living abroad, his “presence on the ground in Russia and his work as a grassroots agitator, propagandist and journalist made him so valuable to Lenin and lubricated his rise to the top of the Bolshevik party. None was fiercer in their criticism of the Mensheviks, but for practical reasons Stalin often favoured party unity.” (p52)

To be continued …

https://thecommunists.org/2025/01/01/ne ... eview-pt1/