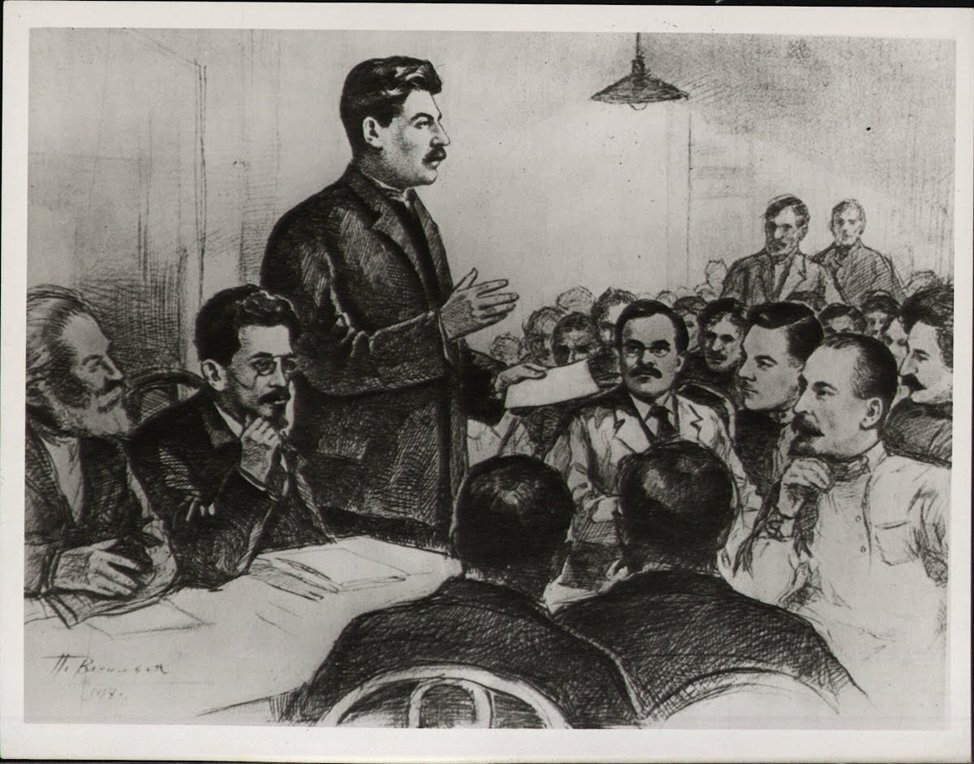

Stalin in October

November 7, 17:13

Stalin in October

On the Eve

Let us dwell on Stalin's political activity in September-October 1917. It is precisely this period that foreign anti-Stalinist researchers seek to present without Stalin, trying to prove that he was a man who remained outside the October Revolution (R. Tucker, R. Slusser). Russian anti-Sovietists echo them. In Solzhenitsyn's recently published extensive article "On the Precipice of Narrative" ("Literaturnaya Gazeta", July 18-24, 2007), dedicated to the October events of 1917, Stalin's name is not mentioned. In it, Trotsky is in the foreground, Lenin - in the background. Everything is like in Trotsky's "Lessons of October". According to the latter, Stalin almost slept through the revolution. This slanderous version is widely disseminated today.

Let us turn to the facts of history that are imprinted in the minutes of the meetings of the Central Committee of the RSDLP(b).

In the minutes of the meeting of the Central Committee on September 15, the central item on the agenda is the question of Lenin’s letters, in which he convinces the members of the Central Committee that “the Bolsheviks can and must take state power into their own hands.”

What is the attitude of the Central Committee toward the leader’s letters? Not at all positive for the majority. The minutes record:

“Comrade Stalin proposes sending the letters to the most important organizations and proposing to discuss them. It is decided to postpone them until the next meeting of the Central Committee.

The question is put to a vote as to who is in favor of keeping only one copy of the letters. For — 6, against — 4, abstained — 6.

Comrade Kamenev makes a motion to adopt the following resolution:

The Central Committee, having discussed Lenin’s letters, rejects the practical proposals contained therein, calls on all organizations to follow only the instructions of the Central Committee, and reaffirms that the Central Committee finds any street actions completely unacceptable at the current moment.”

As we can see, Stalin stood firmly on Lenin's side when anti-Leninist sentiments and hesitations were strong in the Bolshevik leadership - was there not a great risk that the party would go bankrupt if it suffered a defeat?

Behind the minutes of the Central Committee meeting, one must see the fierce struggle between Lenin's supporters and opponents. Stalin's active position as a firm Leninist is obvious in it. In September, he wrote: "The counter-revolution has not yet been defeated. It has only retreated, hiding behind the back of the Kerensky government. The revolution must take this second line of counter-revolutionary trenches if it wants to win"; "The task of the proletariat is to close ranks and tirelessly prepare for the coming battles."

In the decisive weeks of October 1917, Stalin was at the forefront of the main events.

On October 10, a historic meeting of the Bolshevik Central Committee took place. Lenin spoke at it, analyzing the current situation: “The majority is now on our side. Politically, the matter is completely ripe for the transfer of power... The political situation is thus ready. We must talk about the technical side. That is the whole point. Meanwhile, we, following the defencists, are inclined to consider the systematic preparation of an uprising something like a political sin.” By

10 votes to 2 (Kamenev and Zinoviev), a resolution was adopted: an armed uprising was ripe and “the Central Committee proposes that all party organizations be guided by this and discuss and resolve all practical issues from this point of view.”

Stalin was among the 12 participants in the Central Committee meeting. On October 10, the newspaper Rabochy Put published his article, “The Counter-Revolution is Mobilizing – Prepare to Resist,” which was in line with the decision taken at the Central Committee meeting: “The councils and committees must take all measures to ensure that the second uprising of the counter-revolution (the first was General Kornilov’s – Yu.B.) is swept away by the full force of the great revolution.”

At the Central Committee meeting on October 10, a Political Bureau was established “for political leadership in the near future...” The Politburo included Lenin, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Stalin, Sokolnikov, and Bubnov. This is recorded in the minutes.

No less important and historic was the Central Committee meeting

on October 16. Its participants were much more representative than on October 10: in addition to the Central Committee members, many members of the Petrograd Committee, the Military Organization of the Party, and others took part in the meeting. The matter of preparing an armed uprising was transferred from the plane of theoretical disputes to practical tracks. Lenin spoke out to justify his previous position. Analyzing the situation that had developed in the country, he made a harsh conclusion about the need for “the most decisive, most active policy, which can only be an armed uprising.”

The minutes record a heated discussion of Lenin’s speech. In it, Stalin said, in particular, the following: “The day of the uprising must be expedient. This is the only way to adopt a resolution... What Kamenev and Zinoviev are proposing objectively leads to the possibility of the counter-revolution organizing itself; we will retreat endlessly and lose the entire revolution. Why don’t we give ourselves the opportunity to choose the day and conditions, so as not to give the counter-revolution the opportunity to organize itself.” Since the heated debate was about the day of the uprising (Lenin proposed to begin it before the opening of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, scheduled for October 25, and insisted on this), it can be concluded that Stalin spoke out to justify the need to accept Lenin’s proposal. Not everyone agreed with this. Opinions were expressed about the danger of forcing events.

The results of the heated discussion are as follows: 19 people voted for an armed uprising before October 25 (Stalin among them), 2 voted against, 4 abstained.

On October 17, Kamenev and Zinoviev (2 against) came out in the non-party press with their own special point of view - they committed an act of political betrayal.

Lenin's reaction is well known - he addressed a letter (no, not to the Central Committee) to the members of the Bolshevik Party, in which he uncompromisingly declared: "I say frankly that I no longer consider both of them comrades and will fight with all my might, both before the Central Committee and before the Congress, for the expulsion of both from the Party." There was no unanimous support for Lenin in the Central Committee: some decisively condemned Kamenev and Zinoviev, others (there were no fewer of them than the first) believed that they should be removed from the Central Committee and obliged to refrain from making statements against Party decisions in the future, in other words, not to expel them from the Party. Stalin's point of view was unexpected for many. It is set out in the minutes: "Comrade Stalin believes that Kamenev and Zinoviev will submit to the decisions of the Central Committee, proves that our entire situation is contradictory; considers that expulsion from the party is not a recipe, it is necessary to preserve the unity of the party; proposes to oblige these two comrades to submit, but to leave them in the Central Committee." Everyone knew that Stalin could not be suspected of liberalism. And suddenly: expulsion is not a recipe, leave them in the Central Committee. Perhaps for the first time, Stalin did not agree with Lenin. He did not agree on the eve of decisive events (?!).

The author of "The Political Biography of Stalin" N.I. Kapchenko suggested that Stalin's conciliatory position concealed his inner uncertainty about the final outcome of the armed uprising. In our opinion, there is no basis for such an assumption: all of Stalin's previous political activity testifies to the fact that he made decisions, being convinced of their correctness and feasibility, and was able to instill confidence in others in this. An attempt at a psychological analysis of his political behavior is futile: those who undertake it give free rein to their imagination and are detached from objective reality. And at that time it was as follows: Lenin, thanks to his enormous authority, achieved support for his position by the majority of the Central Committee, but the minority (Kamenev and Zinoviev plus four abstentions) reflected the indecision and hesitation of a certain part of the party. Before the historic action - the uprising against the bourgeois power, monolithic unity was necessary. To achieve it in a few days (there were only seven left) by excluding "scabs" - was not realistic. In Stalin's speech justifying the proposal to leave Kamenev and Zinoviev on the Central Committee, the key words were: "the situation is contradictory", "we must preserve the unity of the party". It seems that Stalin's proposal showed the political practicality necessary before the decisive battle. It was precisely this practicality that forced Lenin and the Central Committee to heed Stalin's advice - Kamenev and Zinoviev were left on the Central Committee, obliged to submit to his decision. And they submitted.

Stalin learned a lesson from the situation under analysis. When he took the helm of the party and the state, he excluded any possibility of having opponents of its general line and waverers in the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). This happened on the eve of the battle with a mortal enemy - German fascism.

At the meeting of the Central Committee of the RSDLP (Bolsheviks) on October 16, after the decision on the armed uprising, a party practical center for leading the uprising was established - the Military Revolutionary Center, consisting of Sverdlov, Stalin, Bubnov, Uritsky and Dzerzhinsky. Thus, by October 25, 1917, Stalin worked in two party bodies that were the headquarters of the armed uprising - the Politburo of the Central Committee and the Military Revolutionary Center. At the same meeting of the Central Committee, he was introduced to the Executive Committee of the Soviets and put forward a number of initiatives testifying to his confidence in the victory of the uprising.

On the evening of October 24, Lenin arrives at Smolny. Stalin informs him of the course of political events.

Confrontation

Western Sovietologists and home-grown "researchers" are not the pioneers in the mythology of Stalin. The first to create the myth of his peripheral role in the October Revolution was Trotsky. His confidence that only he had the monopoly right to play the role of leader knew no bounds. Stalin was an obstacle to the implementation of Trotsky's ambitious plans. The latter's authority was noticeably growing in the party, while Trotsky's popularity, which he had always been extremely concerned about, began to melt away. After the end of the Civil War, the time for creation had come. Politics moved from the sphere of war to the sphere of economic affairs - the difficult process of restoring the country's utterly destroyed economy was underway. The troubadour of the permanent revolution, who dreamed of himself as its leader, was not only unprepared for socialist creation in Soviet Russia, but also considered the construction of socialism in a single country a betrayal of the interests of the international revolution. The clash between Trotsky and Stalin was not a struggle for personal power, but a struggle of directions in the development of Soviet society. The fate of October 1917 depended on its outcome. There could only be one winner; history did not allow a draw.

Trotsky was the first to strike at his formidable opponent. He was the first to challenge him. To do this, he chose a weapon he wielded well – historical journalism. In 1924, Trotsky published the book “Lessons of October.” Its main characters are Trotsky himself and Lenin (in that order). Not a word about Stalin, as if he had not been in the revolution. Kamenev and Zinoviev are portrayed as antiheroes. Trotsky writes in detail about their “strikebreaking” on the eve of October, which allows him to make a transparent hint: who suggested leaving them on the Central Committee of the Party? Describing the July events of 1917, Trotsky did not even mention the 6th Party Congress, whose decisions aimed the Bolsheviks at an armed uprising. Such “forgetfulness” reveals the author’s deliberate tendentiousness. He also "forgot" to mention his absence from the Central Committee meeting on October 16, 1917, when the question of revolution was transferred from the sphere of theory to the sphere of political practice - a party practical center was created to lead the uprising (Stalin was one of its members). Trotsky "out of forgetfulness" replaced this center with the Military Revolutionary Committee under the Petrograd Soviet, of which he was a member.

The author of "The Lessons of October" discusses at length Lenin's attitude to the Pre-Parliament, created at the Democratic Conference, with the aim of distracting the masses from the revolutionary struggle. And not a word about the fact that on September 21, at a meeting of the Bolshevik faction of the conference, Stalin delivered a report outlining Lenin's position on the bourgeois forms of "democratic talk." Trotsky remained silent about the most important events on the road to October associated with the name of Stalin.

Trotsky deliberately chose to remain silent about Stalin's role in the great revolution. He needed to declare himself as Lenin's only successor. He needed to provoke the readers of his book to think that Stalin, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Party, could not claim to play such a role: Comrade Stalin was distant from Lenin in the October Revolution, but Comrade Trotsky, like Lenin, was its leader. To discern this subtext of "Lessons of October," one must know and understand the political life of Soviet Russia in 1924. Its main question: who will take the helm of the party leadership and, accordingly, where will the country go?

Trotsky's role in the October Revolution is significant, that is indisputable. But he himself saw and assessed it as exceptional, equal to Lenin's role, and in some ways even superior to it. With excessive vanity and self-admiration, he, in particular, asserted in the "Lessons of October":

"From the moment we, the Petrograd Soviet, protested Kerensky's order to withdraw two-thirds of the garrison to the front, we had already entered into a state of armed uprising. Lenin, who was outside Petrograd, did not appreciate this fact in all its significance...

...After the "quiet" uprising of the capital's garrison by mid-October, from the moment when the battalions refused to leave the city on the orders of the Military Revolutionary Committee and did not leave, we had a victorious uprising in the capital...

...The uprising of October 25 was only of an additional nature."

Thus, according to Trotsky, it turns out that Lenin was wrong to send the "Letter to the Members of the Central Committee," in which he demanded: "Under no circumstances should power be left in the hands of Kerensky and company until the 25th, under no circumstances, the matter must be decided today, certainly in the evening or at night." Today is October 24. It turns out that on that same day, the 24th, the Central Committee of the Party held a meeting to discuss Lenin's letter. The minutes of the meeting, in particular, state: "Trotsky considers it necessary to set up a reserve headquarters in the Peter and Paul Fortress...". What is the point of all this if the “quiet” uprising has already won?..

For Trotsky, the party was only a backdrop for his depiction of his “heroic” role in October. Later, in 1935, he would write in his diary: “If there had been neither Lenin nor me in Petersburg, there would have been no October Revolution.” Comments, as they say, are superfluous. In “Lessons of October,” this idea is contained in the subtext. Stalin was the first to expose it, the first to debunk the legend of Trotsky’s special role in the October Uprising, which was intolerable for the latter.

Speaking at a plenum of the communist faction of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions in November 1924, Stalin said: “The Trotskyists are vigorously spreading rumors that Trotsky was the inspirer and sole leader of the October Uprising. These rumors are being especially vigorously spread by the so-called editor of Trotsky’s works, Lenzner. Trotsky himself, systematically bypassing the party, the Central Committee of the party and the Petrograd Committee of the party, hushing up the leading role of these organizations in the uprising and strenuously promoting himself as the central figure of the October uprising, voluntarily or involuntarily contributes to the spread of rumors about Trotsky's special role in the uprising. I am far from denying Trotsky's undoubtedly important role in the uprising. But I must say that Trotsky did not play and could not play any special role in the October uprising, that, being the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, he carried out only the will of the appropriate party authorities."

And further: "It could not have been otherwise: Trotsky had only to violate the will of the Central Committee to lose his influence on the course of affairs. Talk about Trotsky's special role is a legend spread by obliging "party" gossips.

This does not mean, of course, that the October uprising did not have its inspirer. No, it had its inspirer and leader. But it was Lenin, and no one else."

Stalin put everything in its place.

The defeated Lev took revenge on Stalin for exposing him, Leon Trotsky, until the end of his days. But all this would happen later. Then, in 1924, he did not dare to give a public response.

Stalin would not have been Stalin if he had not asked the question: "Why did Trotsky need all these legends about October and the preparation for October, about Lenin and Lenin's party?" And if he had not answered it: "Trotsky desperately needs to debunk the party, its cadres, in order to move from debunking the party to debunking Leninism. The debunking of Leninism is necessary in order to push through Trotskyism as the "only", "proletarian" (don't joke!) ideology. All this, of course (oh, of course!), under the flag of Leninism, so that the procedure of pushing through would be "as painless as possible."

Stalin revealed the peculiarities of Trotskyism and showed its danger to the fate of October: the substitution of a continuous (permanent) revolution on a global scale for the socialist revolution in Russia (one country); undermining the unity of the party through organizational opportunism ("Trotskyism in the organizational sphere is the theory of cohabitation of revolutionaries and opportunists, their groups and small groups within the bowels of a single party"); the desire to destroy the authority of party leaders ("Trotskyism is distrust of the leaders of Bolshevism, an attempt to discredit them, to debunk them").

If Trotsky had defeated Stalin in their ideological and political battle, the October Revolution, and it continued, would have had a tragic outcome. A crisis of Soviet power would have arisen from the forcible drawing of the country into an adventurous world revolution, which could, with the indispensable assistance of the bourgeois West, have led to the restoration of capitalism in Russia. Its collapse, with the likelihood of a new civil war, would have been inevitable.

Stalin was the first to use the term "new Trotskyism" and defined its characteristic features: the adaptation of Leninism to the demands of Trotskyism (primarily, to the idea of a "pure" proletarian dictatorship, excluding the alliance of the proletariat and the peasantry); the undermining of party unity by "opposing old cadres to the party youth"; the opposition of Lenin, interpreted in a Trotskyist way, to the country's party leadership and its course. The new Trotskyism (neo-Trotskyism in modern terms) differed from the old, pre-revolutionary one only in its tactical tricks. Its strategy remained the same - permanent revolution.

Neo-Trotskyism declared itself under Khrushchev (clearly, in a modern version), but was stopped: the rush to communism, with the hope that war was not fatally inevitable, did not take place. In its bourgeois-liberal edition, neo-Trotskyism showed itself in full measure during the years of Gorbachev's perestroika. Under the slogans "The revolution continues!", "More democracy - more socialism!" Gorbachev and company carried out the dismantling of the party and the Soviet state - capitalism returned to Russia. The Great October was betrayed, its ideals were desecrated.

The positions of Stalin and Trotsky in October 1917 were directly opposite. Their attitude to the great Russian revolution was directly opposite.

Trotsky was forced to call the October Revolution Russian, because that is what Lenin called it. But Trotsky did not want to see anything Russian or national in it. He looked at it as the fuse of a world revolution with its obligatory center in Europe. He linked the fate of October with Europe, the West. Using modern terminology, we will say: Trotsky was a militant Eurocentrist. His internationalism had a Western European character. Today it resembles Western globalism, but in the shell of "permanence": for Trotsky, everything must be decided in the West and by the West. He was never interested in the national interests of Russia. He did not even allow himself to think about the national uniqueness of the October Revolution. He spoke with contempt about the Russian peasantry (read - about the Russian people): "What is our revolution, if not a furious uprising ... against the peasant root of old Russian history."

Stalin was a proletarian internationalist and, like Lenin, for a long time paid tribute to the idea of international revolution. But following Lenin and remaining a proletarian internationalist, he began to think more and more about the national character of the future socialist revolution in Russia - about its Russian character, first of all. There is a basis for such an assumption.

In 1913, in his work "Marxism and the National Question", Stalin notes: "In Russia, the role of unifier of nationalities has been taken on by the Great Russians." In the same work, he concludes: the liberation, i.e. the fate of all the nations of Russia, depends on the resolution of the fate of the Russian question, as an agrarian (peasant) one. Stalin was the first to introduce the concept of the "Russian question" into Marxism and define its international, all-national meaning in Russia.

In 1917, at the VI Congress of the RSDLP(b), answering questions about the report on the political situation, Stalin speaks of the Soviets as the most appropriate form of organizing the struggle of the working class for power and especially emphasizes: "This is a purely Russian form." It was not without his active participation that the resolutions of

the 6th Congress were written - in them the revolution in Russia is called Russian. And in the RSDLP manifesto adopted by the congress, the following expression is found: "English and American capitalists, who as creditors became the masters of Russian life...".

Let us recall once again the polemic between Stalin and Preobrazhensky at the 6th Party Congress. Rejecting the latter's Eurocentric amendment to the congress resolution, Stalin (we quote once again) categorically stated: "We must discard the outdated notion that only Europe can show us the way. There is dogmatic Marxism and creative Marxism. I stand on the basis of the latter." In this regard, R. Tucker, a well-known American political scientist and anti-Stalinist, noted: "This remarkable statement, which deserves even more attention due to its spontaneity, for a brief moment lifted the curtain on Stalin's underlying Russocentrism. In the exchange of opinions, the contours of the future discussion in the party regarding the possibility of building socialism in Soviet Russia without a revolution in Europe emerged, and Stalin's "creative Marxism" of 1917 already contained in embryo the idea of building socialism in one, separate country."

Let us leave the American's sarcasm on his conscience when he speaks of Stalin's "creative Marxism" and say: before October 1917, Stalin thought in categories of world and national, Russian history; he was aware of such an important national-historical feature of Russia as the leading role of the Russian people in its formation and development. Even then, Stalin thought as a revolutionary politician, a statist, Trotsky - as a "revolutionary" cosmopolitan, a Westerner. Their irreconcilable confrontation was inevitable.

Trotsky's emphasis on his exceptional role in the history of October and his deliberate hushing up of Stalin's role is beneficial to all anti-Sovietists - from Western Sovietologists with the Radzinskys and Mlechins who joined them, to the so-called patriots of today, who trace their lineage back to the pro-Entente Denikin and Kolchak. The former hate the national nature of the great Russian revolution, the latter - its class nature. Stalin, like Lenin, combined these two hypostases of October.

Through the efforts of Trotsky and the Trotskyists, the process of devaluing Stalin's role in October 1917 began. Today, Trotsky has been "revived" to continue this process - Stalin is feared in the West and in the pro-Western ruling circles of Russia even after he has died.

The greatest revolutionary and politician of the 20th century, he showed himself to be a man of extraordinary intelligence and will in the history of October. In October, Stalin was next to Lenin. Then no one could have imagined that a genius was next to a genius. This is now clear to anyone who tries to objectively evaluate the history of the past century.

(c) Yuri Belov

P.S. It is worth remembering that Stalin was not only a great leader and builder of a superpower, but also a great revolutionary.

https://colonelcassad.livejournal.com/9483058.html

Google Translator