August 26, 2025

Universal access to safe water and sanitation is increasingly out of reach

In Zambia, a boy scoops water out of a ditch below an outhouse. (© UNICEF/UNI598555/Sampa)

Billions of people around the world still lack access to essential water, sanitation, and hygiene services, putting them at risk of disease and deeper social exclusion.

A new report by the World Health Organization and UNICEF: Progress on Household Drinking Water and Sanitation 2000–2024: special focus on inequalities – launched during World Water Week 2025 – reveals that, while some progress has been made, major gaps persist. People living in low-income countries, fragile contexts, rural communities, children, and minority ethnic and indigenous groups face the greatest disparities.

This update – produced by WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP) – provides new national, regional and global estimates for water, sanitation and hygiene services in households from 2000 until 2024. The report also includes expanded data on menstrual health for 70 countries, revealing challenges that affect women and girls across all income levels.

Key facts from the report

♦ Despite gains since 2015, 1 in 4 – or 2.1 billion people globally – still lack access to safely managed drinking water, including 106 million who drink directly from untreated surface sources.

♦ 3.4 billion people still lack safely managed sanitation, including 354 million who practice open defecation.

♦ 1.7 billion people still lack basic hygiene services at home, including 611 million without access to any facilities.

♦ People in least developed countries are more than twice as likely as people in other countries to lack basic drinking water and sanitation services, and more than three times as likely to lack basic hygiene.

♦ While there have been improvements for people living in rural areas, they still lag behind. Safely managed drinking water coverage rose from 50 per cent to 60 per cent between 2015 and 2024, and basic hygiene coverage from 52 per cent to 71 per cent. In contrast, drinking water and hygiene coverage in urban areas has stagnated.

♦ Data from 70 countries show that while most women and adolescent girls have menstrual materials and a private place to change, many lack sufficient materials to change as often as needed. Adolescent girls aged 15–19 are less likely than adult women to participate in activities during menstruation, such as school, work and social pastimes.

♦ In most countries with available data, women and girls are primarily responsible for water collection, with many in sub-Saharan Africa and Central and Southern Asia spending more than 30 minutes per day collecting water.

♦ As we approach the last five years of the Sustainable Development Goals period, achieving the 2030 targets for ending open defecation and universal access to basic water, sanitation and hygiene services will require acceleration, while universal coverage of safely managed services appears increasingly out of reach.

https://climateandcapitalism.com/2025/0 ... ing-water/

******

U.S. and oil producers block a treaty to clean the world of plastic pollution

Originally published: Liberation News on August 18, 2025 by Tina Landis (more by Liberation News) | (Posted Aug 25, 2025)

Landis is the author of the book Climate Solutions Beyond Capitalism.

The fifth session of the UN Plastics Treaty negotiations ended on Aug. 15, once again in a deadlock. Over 100 countries came to the table, with the majority pushing for a binding agreement to cut plastic production, determine when plastics become waste, and limit the toxic chemicals used in plastics. Talks are set to resume at a future date, far beyond the deadline that had been set for an agreement.

As with other UN negotiations, such as the annual COP meetings on climate change, the U.S. and its allied petrostates continue to block any significant progress despite a majority of countries seeing the need to rapidly shift off fossil fuels and their byproducts, such as plastics. Frustration with the process was conveyed by Dennis Clare of Micronesia, who said, “What might have collapsed is not so much the talks but the logic of continuing or concluding them in a forum with dedicated obstructionists.” (Plastic pollution talks fail as negotiators in Geneva reject draft treaties | Plastics | The Guardian)

In 2022, the UN set the goal of establishing a global Plastics Treaty by the end of 2024, recognizing the need to address the plastics pollution crisis through a legally binding agreement. That mark was missed once again with the U.S., along with petrostates like Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, refusing to make any concessions that would limit production and restrain their ability to profit off of this fossil fuel-driven industry. They instead argued that the focus should solely be on waste management rather than addressing the source of the problem—plastics production itself.

Of the approximately 2,600 participants at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee Plastics Treaty negotiations, 234 registrants were fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists —up from 221 at the previous session. This blatant interference by the very industries who have caused the environmental crisis calls into question the viability of any honest negotiations occurring through these UN bodies.

Plastics pollution is the second biggest environmental threat

According to the UN, plastic pollution is the second biggest threat to our global environment after climate change. Four hundred million tons of new plastic are produced globally each year with projections estimating a 70% growth in production by 2040. Plastics will take centuries to tens of thousands of years to completely break down, depending on the chemical makeup of the specific plastic. Instead of degrading like other materials, such as metal or glass, it instead breaks down into microscopic particles that are now prevalent everywhere—in the air we breathe, in rain and snow, in the food we eat, the water we drink, and even in human embryos. The toxic chemicals used in plastics act as neurotoxins, cause cancer and birth defects, disrupt our hormones and create infertility.

On top of the health impacts from its breakdown in our environment, the primary location of domestic plastics production is in the “Chemical Coast” of Texas and Louisiana, where a high concentration of industry poisons low-income communities and communities of color.

First created in 1907, plastics weren’t manufactured on a mass scale until after World War II, with 2.2 million tons produced in 1950. The 1970s saw an explosion of single-use plastics with overall production climbing to 407 million tons in 2015. The Coca Cola Corporation is the world’s largest producer of plastic waste, outsourcing this waste problem to every corner of the globe through their products.

Twenty-two tons of plastic waste enters the oceans every minute! Many remote areas and less developed countries don’t have the capacity for comprehensive waste management programs and with the influx of consumer goods—that generally contain plastic—waste ends up being washed into river systems during heavy rains and on to the ocean. Plastic is so prevalent in the products we use that it’s nearly impossible to avoid—from food wrappers and packaging to clothing, vehicles and technology, and nearly every household item—plastics are everywhere. It is predicted that plastics will outweigh fish in our oceans by 2050 if we continue on the current trajectory.

In the 1970s in response to the environmental movement that demanded solutions to waste and pollution, recycling programs were created. Industry pushed recycling as a tactic to diffuse peoples’ valid concerns, but never divulged the significant limitations to recycling plastics. Since the advent of recycling, only 10% of plastics have ever been recycled, partly due to the economic cost of recycling. Also, the unique properties of each plastic polymer used in various products require different processes to recycle, which are often trade secrets, so only the corporation that produced the polymer knows exactly what is in it.

Plastic waste is outsourced to to the global south

Just as the U.S. outsources its greenhouse gas emissions by outsourcing production to the Global South, it also avoids its solid waste problem by diverting it to lower-income countries. In 2018 alone, the U.S. shipped 1.07 million tons of its plastic waste to global south countries that often lack the infrastructure to manage and recycle the waste.

Even when plastics are recycled, they still end up in our environment one way or another. Through one recycling method called “downcycling,” plastics are ground into tiny fibers, which are then used to create other products like clothing, which when washed in our laundries sheds microplastics into our water systems. Thirty-five percent of microplastics in our environment are from synthetic clothing fibers. This downcycling is also limited to only two cycles before the source material is too degraded for use in new products.

Other so-called recycling processes include “advanced recycling” and “chemical recycling,” which are just greenwashing terms for incineration. As of 2020, the greenhouse gases created by plastic production and incineration of plastic waste equaled the emissions of 500 large coal-fired power plants.

So why are we still producing plastics in mass quantities every year? The answer is the profit motive.

Fossil fuel giants see profits from plastics as their ‘plan B‘

Around 6% of annual oil production goes to plastics. So not only do plastics provide low-cost, light-weight packaging and materials, which increases profits of corporations, but they also provide another market for fossil fuels beyond the energy sector. Plastics are seen as a “Plan B” for fossil fuel companies. As their profits are threatened by the transition to renewable energy, plastics production is being ramped up along with lobbying efforts that help to undermine a shift off their toxic products through a binding Plastics Treaty.

But there is another way. First, we need to greatly reduce waste in general and eliminate single-use plastics. Second, we can go back to using refillable glass and metal containers or biodegradable materials.

Sustainable solutions are available, but don’t generate profits for a few

Ninety percent of plastics used today could be made from plant-based materials, such as brown kelp, which degrades within 4 to 6 weeks. Kelp is one of the fastest growing plants on the planet, growing up to one meter per day. And kelp forests have other environmental benefits, such as filtering pollutants from waterways and alleviating nutrient run-off from agricultural fields and wastewater outflows, which reduces the occurrence of toxic algae blooms. Kelp forests also create vital habitat for a myriad of species, increasing biodiversity and reducing ocean acidification.

Through human ingenuity and sharing of research and technologies across borders, as well as an end to the consumer culture pushed onto the world by the West, we could find many truly sustainable solutions to the plastic pollution crisis.

Under capitalism, what is produced, how much is produced, what materials are used and how much waste is created is determined based on what is most profitable for the ruling elite who own these industries. This ruling elite, who benefit from the fossil fuel and plastics industries, will continue to undermine any attempts at environmental protections as they always have throughout the existence of capitalism.

Only through mass movements of the people—that threatened their continued profits—have any protections been won in the past. The U.S., along with the petrostates—which would collapse without the sale of their fossil fuels—will continue to be a barrier to the changes that are needed for a livable future. Only a socialist planned economy and global cooperation can solve the crisis that we are facing and move us to long-term environmental sustainability.

https://mronline.org/2025/08/25/u-s-and ... pollution/

******

Extinction by Design: How Liberal Environmentalism Narrates Our Alienation from Nature

We strip the green paint off the empire’s lies, lay out the hard facts of how capital severs us from the land, turn the whole story on its head with a revolutionary view, and end with a battle plan to break the grip of those who hoard the earth’s food and soil.

By Prince Kapone | Weaponized Information | August 16, 2025

Part I – Extinction of Experience as Class War

The scientists call it a “60% decline in nature connectedness” over two centuries. The Guardian dresses it up in the soft language of “lifestyle change” and “urban distraction.” But let’s strip away the varnish: this is not an accident of modern life. This is class war against the senses, waged by a capitalist system that treats every living thing as raw material for profit and every human being as labor-power to be drained. It is the slow, methodical confiscation of our ability to feel at home in the world that made us. And like all capitalist theft, it is deliberate, organized, and defended by an entire cultural apparatus designed to make you forget what’s been stolen.

The Derby University study confirms what millions already know in their bones: people are being born into cities where the grass is manicured into corporate logos, where the air smells of exhaust instead of rain, and where a child’s only encounter with a bird might be the animated one on a phone screen. The research traces this rupture over 220 years, mapping the erasure of nature words like river and blossom from our books, the shrinking of wildlife in our neighborhoods, and—most damning—the collapse of intergenerational transmission. Parents no longer pass down the knowledge, habits, and affections that once made engagement with the natural world as natural as breathing.

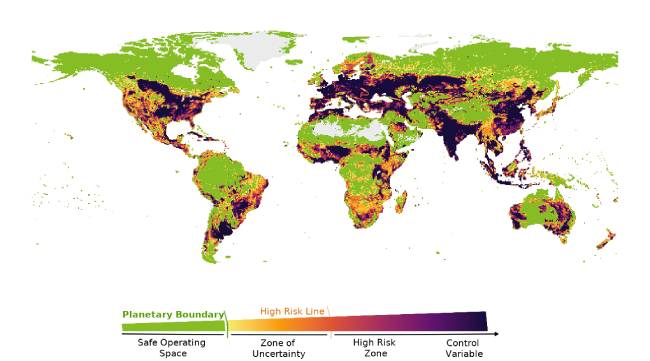

Under capitalism, this “extinction of experience” is not a bug—it’s a feature. The less we feel part of the living world, the easier it is for capital to pave it over, commodify it, and sell it back to us in the form of wellness retreats and nature documentaries. Marx understood this metabolic rift: that capitalism severs the organic interchange between human beings and the rest of nature, not because it is irrational, but because it is ruthlessly rational—from the standpoint of profit. Kohei Saito calls it the unfinished critique of political economy: to grasp that ecological collapse is not just a byproduct of capitalism, but its structural necessity.

And so the baseline drops. As John Bellamy Foster has shown, the ruling class adapts to ecological crisis by redefining it as a technical problem, solvable by market tweaks and “green growth” schemes. The Guardian article offers a gentler version of the same: schoolyard greening projects, urban parks, and “30% more green space” as balm for a century of alienation. But the Derby model says otherwise: we’d need cities ten times greener just to reverse the trend. In capitalist terms, that’s heresy—because it would mean reconfiguring land use, production, and ownership in ways that put human and ecological well-being before profit.

The ruling class won’t do it. But others have. Cuba’s post-Soviet “special period” saw a collapse in imported oil and fertilizers, forcing the turn to agroecology, urban gardens, and community food sovereignty. China’s policy of “ecological civilization” recognizes—at least in principle—that you cannot endlessly degrade the biosphere without undermining social stability. These are not utopias. They are contested, imperfect, and contradictory. But they show that the metabolic rift can be narrowed when the political will exists to subordinate private profit to collective survival.

In the imperial core, however, the logic runs the other way. The fewer people who walk barefoot in the soil, the fewer who recognize a bird’s call, the easier it is to sell the lie that nature is “out there” somewhere—external, exploitable, and ultimately expendable. What The Guardian calls “declining connectedness” is in fact the ideological groundwork for permanent ecological austerity. And unless we call it what it is—a conscious program of alienation rooted in the political economy of capitalism—any talk of “reconnection” will be just another product on the shelf.

Part II – The Political Economy of Disconnection

The polite story is that we’ve drifted from nature because of “modern distractions” — screens, commutes, busy schedules. The truth is uglier: our disconnection is the planned outcome of a political economy that treats the living world as a commodity frontier, not a commons. It’s not a glitch that urban residents spend barely four minutes and thirty-six seconds a day in natural spaces — a figure confirmed by researchers from the University of Derby in The Guardian.

Capitalism has no incentive to preserve a population’s ecological literacy. In fact, as the theory of the “metabolic rift” in global political economy makes clear — that capitalism severs nutrient and knowledge cycles between people and the land — the system benefits from replacing ecosystem fluency with brand fluency. This concept is defined in the accessible Monthly Review article on Marx’s ecological insights on the metabolic rift.

Advertisement

Environmental sociology confirms that disconnection from nature among urban populations is structural, not accidental — woven into how our cities are built and governed. Studies show that spending just 120 minutes a week in natural environments significantly boosts well-being, an insight that underscores how deeply we’ve lost connection with everyday access to nature via the protected organizational time-in-nature study.

This is why the Guardian’s suggestion of “30% more urban green space” feels like a corporate brochure. According to the Derby model, reversing disconnection would require cities to be ten times greener “we’d need cities ten times greener”. That’s not a tweak — that’s a direct attack on real estate capital, infrastructure monopolies, and the fossil-fuel economy.

Examples from socialist and post-colonial worlds show what true transformation demands. Cuba’s urban agriculture revolution of the 1990s turned vacant lots into agroecological production zones, vastly boosting local fresh produce access — documented in FAO reports by the FAO — and urban gardens produced up to 50% of Havana’s fresh produce according to US News.

Likewise, China’s ecological civilization policy integrates environmental restoration, biodiversity, and carbon targets into national planning — a sovereign vision that ties ecological health to social stability, clearly explained in an accessible paper on China’s strategy via ADB’s ecological civilization report.

Advertisement

In the capitalist core, however, the solutions on offer amount to biospheric austerity: privatized parks, “green” condos, or token corporate sponsorships of community gardens—branding nature as lifestyle, not belonging. Critical research exposes how neoliberal “green” policy turns ecological crises into fresh accumulation opportunities, rather than restoring connection in the critique of market environmentalism.

To restore genuine connection at the scale science demands would mean contesting capital’s control over land, labor, and life. The political economy of land use — which links our alienation from nature inseparably to our alienation from one another — is the terrain of this struggle. Accessible research on ecological civilization and urban land governance makes this clear via the political economy of land use analysis. Thus, forest-school nurseries to urban food sovereignty are questions of class power. Land either serves life — or it serves capital. There is no middle ground between extinction and survival.

Part III – Alienation as a Colonial Invention

If the first fact is that people are severed from the land, and the second is that capitalism requires this severance, then the third is that alienation itself was engineered as a weapon of empire. The Guardian’s data on a 60% decline in nature connectedness over two centuries does not mark a slow cultural drift — it measures the long arc of deliberate dispossession. This arc begins not in the shopping malls and screen addictions of the late 20th century, but in the enclosures, plantations, and genocides that made modern capitalism possible.

Advertisement

From the 16th century onward, European colonialism imposed an extractive land regime that criminalized subsistence, privatized commons, and redefined human beings as labor inputs. In Britain, the enclosure of common land drove peasants off ancestral soil; in the Americas and the Caribbean, plantations converted biodiverse landscapes into single-crop factories worked by enslaved Africans; in settler colonies like Australia, entire Indigenous ecologies were bulldozed to make way for sheep and wheat. Disconnection from the land was not a byproduct — it was the precondition for capitalist accumulation.

This is why the loss of “nature words” from books, noted in the Guardian study, carries a deeper meaning. Colonial-capitalist rule always seeks to erase the vocabulary of resistance — to strip the imagination of the terms in which life outside the market can be envisioned. As environmental historian William Cronon has shown, even the concept of “wilderness” was reframed by empire: once the home of Indigenous nations, it became in European eyes a raw commodity frontier or a tourist spectacle in his essay “The Trouble with Wilderness”. Language was remade to fit the ledger.

Under industrial capitalism, this alienation was rationalized as “progress.” In the 19th century, positivist science and imperial geography turned landscapes into data points, soil fertility into yield per acre, and rivers into shipping lanes. By the 20th, advertising and consumer culture had recoded the very meaning of the natural world — not as a living community to which humans belong, but as scenery, lifestyle branding, or a resource to be “managed.” These ideological shifts were not neutral; they disciplined entire populations into accepting ecological collapse as normal and inevitable.

Today, technofascism refines this tradition. Greenwashing and “net zero” pledges function as ideological counterinsurgency, pre-empting radical ecological demands by rebranding the status quo as sustainable. Nature is fed into predictive algorithms, its “services” priced and traded, while the working class is told that personal lifestyle changes are the frontline of the climate fight. This is the political economy of alienation in its most advanced form: the ruling class manufactures disconnection, then sells it back as connection.

Understanding alienation as a colonial invention forces a different conclusion. Reconnecting with nature is not simply a matter of planting more trees in cities or running school trips to the countryside. It is a matter of decolonizing land, abolishing property relations that turn ecosystems into commodities, and dismantling the ideological machinery that teaches us to see the Earth through a profit lens. Only then can the “extinction of experience” documented by the Guardian be reversed — not by nostalgia for a lost rural idyll, but by revolutionary transformation of our relationship to the land.

Part IV – Revolutionary Ecology in Practice

If the first three parts have tracked the disease — capitalist alienation from the land, deepened by the colonial contradiction — then here we turn to those rare and vital experiments where the patient was treated not with palliative reforms, but with structural surgery. We’re not talking about “green cities” built to make gentrifiers feel virtuous, or corporate tree-planting schemes calibrated to the quarterly report. We’re talking about revolutionary states and movements that reorganized production, land, and urban life so thoroughly that the metabolic rift itself began to close.

Look at Cuba in the 1990s. When the Soviet Union collapsed and U.S. imperialism tightened the blockade, the island lost over 80% of its food and fuel imports. Capitalism’s prescription would have been mass starvation, IMF shock therapy, and foreign agribusiness carving up the countryside. Instead, Cuba turned to urban agriculture on a national scale, transforming vacant lots and rooftops into organic farms, integrating food production into schools and workplaces, and drastically reducing chemical inputs. Within a decade, Havana had over 8,000 urban farms, producing hundreds of thousands of tons of fresh produce locally and covering more than 35,000 hectares of cultivation.

Or take China’s “Ecological Civilization” framework. Whatever contradictions and capitalist encroachments the Chinese model contains, it has made massive state-directed investments in ecological restoration. China mobilized large-scale ecosystem recovery across varied terrains — from mountains to coastal estuaries — through government-led programs like the Shan-Shui initiative that blend traditional practice with modern science.

Even at the municipal level, socialist-oriented governments have proven the point. In Kerala, India, the People’s Plan Campaign devolved planning power to local councils, expanded public food distribution, and embedded agricultural revival into a broader political project of social welfare. This is what it means to think beyond the charity model of “connecting kids to nature” — it’s the deliberate political construction of a society in which human survival is inseparable from ecological health.

These examples are not perfect, and they are not immune to capitalist pressures. But they are proof that when power shifts from capital to the organized people — when the logic of accumulation is replaced by the logic of survival — the so-called “inevitable” extinction of experience can be reversed. That’s the lesson imperialism fears most: not that humans can reconnect with nature in a personal, apolitical way, but that such reconnection is the by-product of dismantling the social order that alienated us in the first place.

Part V – Cities as Battlefields of the Metabolic Rift

Urban space is not neutral. It is designed, policed, and commodified to serve the ruling class. The concrete and steel that stretch across the skyline are not mere symbols of “progress” — they are the physical manifestation of capitalist priorities, where land is a speculative asset, housing is a commodity, and public space is an afterthought or a luxury. The same system that drains wetlands to build luxury condos will spend millions on artificial “green walls” to soften the blow of its own ecological vandalism. The result is cities that alienate their inhabitants from the natural world while locking them into dependence on corporate-controlled infrastructure.

This alienation is not accidental; it is an instrument of class power. As David Harvey has shown in his analysis of the right to the city, urban design is a mode of capital accumulation. Gentrification displaces working-class communities from neighborhoods with parks and mature tree cover, pushing them into heat islands with no shade, polluted air, and little access to fresh food. Public green space becomes a tool of exclusion, fenced off behind paywalls or redesigned to attract tourists and investors rather than serve local needs. Meanwhile, policing is deployed to keep the poor “in their place,” making even the act of being in a park or by the water a criminalized risk for marginalized youth.

The ecological dimension of this urban warfare is often hidden. Studies consistently show that low-income and racially oppressed communities suffer from higher environmental burdens and lower access to green space, contributing to poorer health outcomes, higher rates of mental illness, and increased vulnerability to climate shocks. The ruling class may mouth platitudes about “resilience” and “sustainability,” but their urban policies ensure that resilience is privatized and sold to those who can pay, while the rest are left to bear the brunt of ecological breakdown.

Revolutionary urbanism flips this script. In Havana, the transformation of empty lots into food-producing gardens was not simply about growing vegetables — it was about reclaiming land from the speculative market, turning it into a commons governed by the people who live there. In Caracas, communal councils have fought to integrate urban agriculture and public services into socialist planning, breaking down the divide between “city” and “countryside.” In both cases, the city is not treated as an ecological dead zone but as a living part of the biosphere — and its working-class residents are positioned as stewards rather than passive consumers of their environment.

For the urban working class in the imperial core, this lesson is critical. The fight for housing, public transit, and climate adaptation is inseparable from the fight for green space, clean air, and collective control over land use. Demands for urban rewilding, free public gardens, and community-owned renewable energy are not fringe “environmentalist” causes — they are class demands, direct challenges to the capitalist order of the city. In this sense, the battle to close the metabolic rift runs straight through the heart of the metropolis, and victory there will depend on our ability to turn every park, vacant lot, and rooftop into a node of collective survival.

Advertisement

Part VI – Soil, Seeds, and Sovereignty

The ruling class likes to pretend that food comes from the supermarket. By severing the visible link between the soil and the plate, capitalism turns the most basic human necessity into a commodity mediated entirely by corporations. The global food system, dominated by a handful of agribusiness giants, is designed to extract profit at every stage — from patented seeds to chemical inputs, from fossil-fuel-based transport to retail. In this system, the land is stripped for yield, monocultures replace biodiverse ecosystems, and rural communities are reduced to low-wage labor pools or pushed into urban slums. The result is a planetary agriculture that feeds capital while starving the earth, and increasingly, its people.

This alienation from food production is as political as it is ecological. Imperialist agriculture functions through dependency: the colonized world is locked into exporting cash crops for foreign markets, while the imperial core imports cheap food grown under super-exploitative conditions. When countries resist — when they attempt to protect small farmers, promote local food sovereignty, or reject genetically modified seed monopolies — they face economic sanctions, trade blackmail, and, in some cases, outright regime change. Food becomes both a weapon and a bargaining chip in the arsenal of hyper-imperialism.

Revolutionary movements have long understood that liberation requires control over the means of subsistence. In Cuba, the collapse of Soviet trade in the 1990s forced a radical restructuring of agriculture. The country turned to agroecology — organic inputs, urban gardens, and decentralized production — not just to survive the U.S. blockade but to create a system less vulnerable to the fluctuations of global capital. In Venezuela, the Bolivarian process sought to expand communal control over farmland, providing seeds and technical assistance to local producers to reduce dependency on imports. In both cases, food production was reframed as a collective right and responsibility, inseparable from national sovereignty.

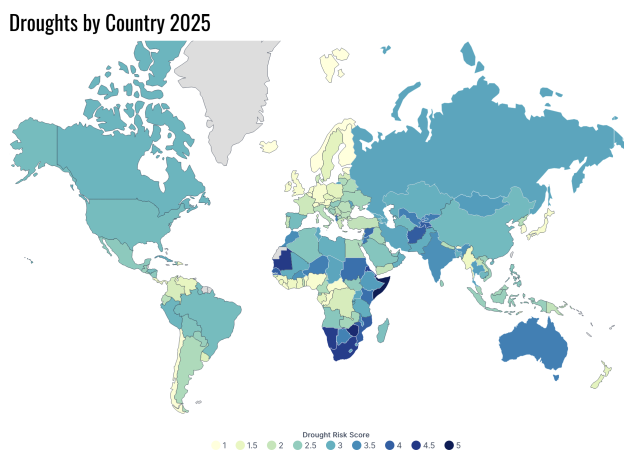

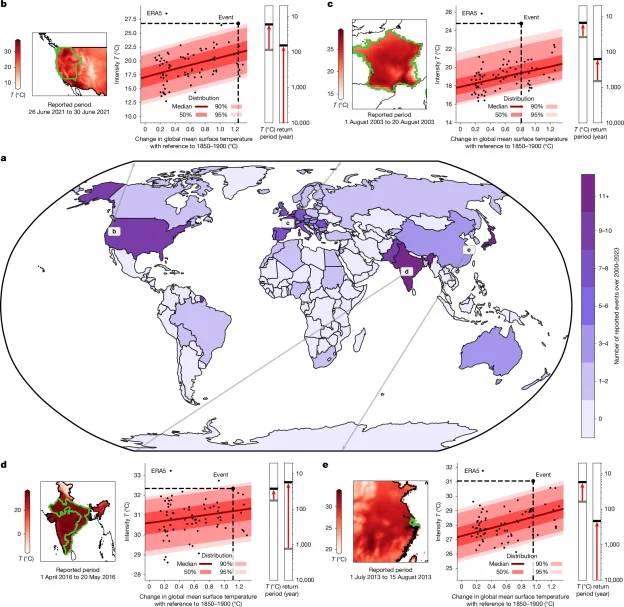

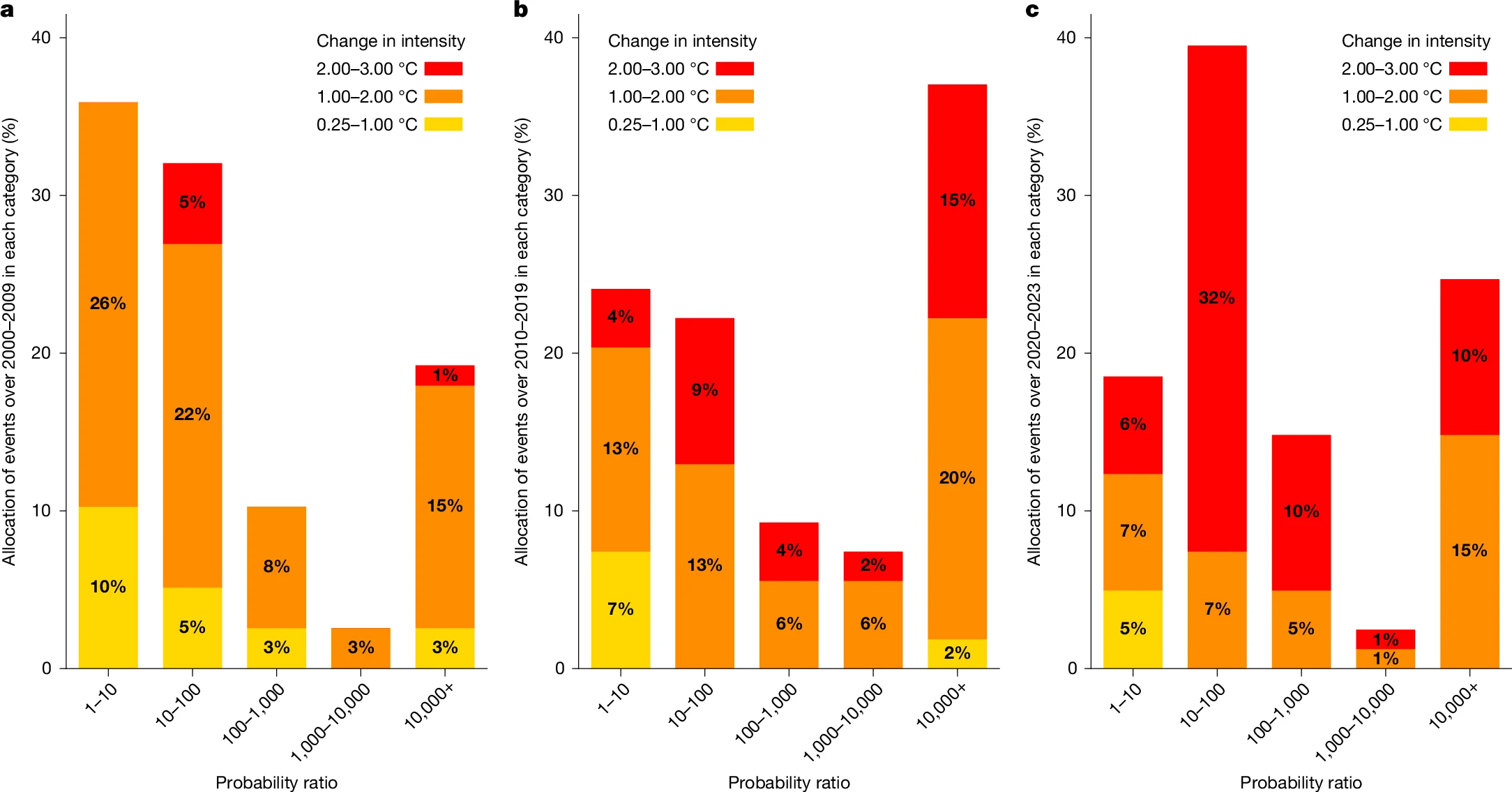

The stakes are even higher in the era of climate breakdown. Droughts, floods, and soil degradation are eroding the stability of industrial agriculture. Meanwhile, multinational agribusiness pushes “climate-smart” solutions that deepen dependency: drought-resistant GMO seeds controlled by patents, carbon offset schemes that enclose more land for private profit, and digital surveillance of farmers’ practices through proprietary platforms. The language is green, but the logic is colonial. Critics note that climate-smart agriculture serves corporate control, reinforcing concentration of power and farmers’ dependency.

Against this, food sovereignty offers not just an ecological alternative but a revolutionary horizon. It means reclaiming the seed commons from corporate control, protecting and regenerating soil health, and integrating agriculture into the cultural and political life of communities. It is about producing food for people, not profit; about linking rural producers and urban consumers in direct solidarity; about building systems resilient to both market shocks and climate chaos. In a socialist framework, this is not a romantic return to the past — it is a conscious reweaving of the human–nature metabolism on terms that serve the needs of the working class and the planet.

The lesson is clear: without sovereignty over our soil and seeds, there can be no sovereignty at all. And without breaking the imperialist food regime, the metabolic rift will only deepen. The path forward demands that we see every farm, every seed bank, and every community garden as a front in the class struggle — as vital to the liberation of humanity as any picket line or barricade.

Part VII – Ecological Civilization as Revolutionary Governance

If the capitalist world order has mastered anything, it is the art of giving the illusion of environmental care while continuing ecological plunder. In the imperial core, “green transition” often means a new round of resource grabs in the Global South — lithium from Bolivia, cobalt from the Congo, rare earths from Myanmar — all wrapped in the rhetoric of “net zero.” These policies do not challenge the logic of accumulation; they simply repaint the machine. The question for revolutionary forces is not how to green capitalism, but how to build an economy where the health of ecosystems is a governing principle, not an afterthought.

China’s framework of ecological civilization offers one such approach — not as a finished model, but as a live experiment in integrating environmental goals into the core of socialist planning. Enshrined in the constitution, the concept recognizes that economic development and ecological health must be coordinated, and that large-scale public investment in reforestation, pollution control, and renewable infrastructure is a matter of public necessity, not market discretion. By mobilizing state capacity for programs like the Grain-for-Green Program — converting degraded farmland back into forest and grassland — China has demonstrated that rapid, large-scale ecological restoration is possible when profit is not the ultimate arbiter.

Vietnam, with its socialist-oriented market reforms (Đổi Mới), has pursued a parallel path on a smaller scale, using land reforms and environmental restoration to adjust rural livelihoods and restore ecosystems, especially in coastal zones through mangrove restoration.

In the Indian state of Kerala, the Left-led government’s people’s planning campaign has linked environmental protection to participatory budgeting, ensuring that local councils have direct say over water conservation, waste management, and biodiversity initiatives. These are not simply “green policies”; they are efforts to embed ecological repair into the very mechanisms of governance, breaking from the capitalist assumption that environmental health must be subordinate to GDP growth.

Across Latin America, Indigenous-led movements have pushed the concept of buen vivir — “living well” — into national constitutions in Bolivia and Ecuador, redefining development around community well-being and ecological balance rather than extraction and accumulation through legal reforms and Rights of Nature recognition. Though constrained by the pressures of global capital, these principles have inspired tangible policy: community forestry, legal rights for rivers and forests, and the rejection of certain mega-mining projects.

In Africa, countries like Burkina Faso and Ethiopia have undertaken massive reforestation drives that, while not socialist in orientation, still illustrate how public mobilization around ecological goals can yield measurable results when tied to national development agendas.

What unites these diverse examples is not a single blueprint, but a shared refusal to accept the capitalist trade-off between ecology and economy. They show that large-scale ecological transformation is not a utopian dream; it is a question of political will, social ownership, and mass participation. Where capitalism treats nature as an externality to be managed, these experiments treat it as a foundation to be restored and sustained.

For the revolutionary movement, the lesson is strategic: ecological civilization cannot be a technocratic add-on. It must be a central line of struggle, a concrete expression of sovereignty and class power. In the Global South, it means breaking dependency on imperialist trade systems that demand ecological sacrifice. In the imperial core, it means dismantling the corporate stranglehold over energy, agriculture, and infrastructure, and reorienting production toward the restoration of the human–nature metabolism. Without this reorientation, “green” will remain just another color in the imperialist flag.

Part VIII – Cities as Commons: Urban Ecology for Proletarian Survival

Capitalist urbanization is a machine for severing people from the land. It concentrates labor where capital wants it, alienates us from food, water, and green space, and leaves the working class dependent on corporate supply chains and imported commodities. In this design, cities are not meant to feed themselves; they are meant to consume — endlessly, hungrily — until both the hinterlands and their own inhabitants are exhausted. The result is a double dependency: the urban proletariat depends on capital for survival, and capital depends on the extraction of resources from distant territories, often through imperialist plunder.

Yet the city can be repurposed. When socialist planning and popular mobilization take the urban terrain seriously, it becomes possible to turn cities into living ecosystems that sustain their people. The Cuban experience after the collapse of the Soviet Union remains one of the clearest proofs. Faced with the loss of 80% of its imports, including food and fuel, Cuba launched a nationwide experiment in organopónicos — intensive organic gardens embedded in urban neighborhoods. By mobilizing workers, students, retirees, and local committees, Havana alone produced enough vegetables to meet a significant share of its residents’ needs, without relying on chemical fertilizers or long-distance transport. This was not just agriculture; it was sovereignty, grown in the cracks of the imperial blockade.

Research from Urban Food Production for Ecosocialism confirms what Cuba demonstrated: urban agriculture under public or community control shortens supply chains, reduces dependence on fossil fuels, strengthens food security, and builds social solidarity. In cities from Rosario, Argentina to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, municipal support for community gardens, rooftop farms, and green corridors has improved nutrition, created local jobs, and restored degraded spaces. These are not boutique projects for the middle class; they are working-class infrastructure, especially when tied to broader housing, transport, and public health systems.

Vietnam’s peri-urban aquaculture systems, integrating rice paddies, fish ponds, and vegetable plots, offer another model. In Kerala, India, local self-governments have invested in urban farming cooperatives that reclaim vacant lots and rooftops for food production, guided by participatory planning. In Nairobi’s informal settlements, vertical sack gardens have allowed families to produce greens even where land is scarce, cutting food costs and improving diets. In all these cases, the practice of producing food where people live is more than an environmental gesture; it is a form of class resilience, reducing the grip of corporate agribusiness and imperialist trade dependency.

Urban greening must also confront the contradiction of gentrification. Under capitalism, green space in working-class neighborhoods often triggers displacement, as property developers and landlords see rising value. Ecosocialist urbanism demands that the benefits of ecological restoration — cleaner air, shade, cooler microclimates, food gardens — be socially owned and democratically managed, insulating them from market speculation. In this sense, the fight for the urban commons is inseparable from the fight against landlordism and speculative capital.

Turning cities into commons is not romanticism; it is strategic necessity. In the coming decades of climate instability, urban populations — especially in the Global South — will face increasing pressure from heatwaves, food price shocks, and supply disruptions. The choice is stark: allow corporate capital to manage this crisis for profit, or reclaim the means of urban survival through collective control of land, water, and green infrastructure. The examples already exist. They only need to be scaled, defended, and embedded within the broader revolutionary transformation of society.

Part IX – Healing the Rift: Political Economy of Ecological Reconnection

Marx called it the metabolic rift — the rupture in the nutrient and energy cycles between humans and the rest of nature, ripped open by capitalist production. Under the old agrarian systems, nutrients extracted from the soil by crops would return via manure and organic waste. Capitalism broke this cycle, turning the countryside into an extraction zone and the city into a sink of waste. Food, fiber, and fuel flowed in one direction, but the metabolic balance never flowed back. The soil in the colonies was stripped to exhaustion, and the working-class districts of the industrial cities rotted in filth, their refuse dumped into rivers or seas rather than returned to the land.

Today, this rift is planetary. Global commodity chains push monoculture agriculture to the edges of tropical forests, leach soils with chemical inputs, and displace rural populations into megacities. The nutrients and energy embedded in their production do not return to their source — they pile up as waste or pollution in overbuilt urban centers, while the soils that fed them become barren. This is not an ecological accident; it is the logic of capital accumulation, which thrives on linear throughput rather than circular renewal.

Ecosocialist reconstruction begins with closing this rift — not with nostalgic fantasies about “returning to the land,” but with deliberate, planned reconnection of the metabolic cycles between city and countryside. In Marx’s Ecology, John Bellamy Foster demonstrates how Marx saw this not as a technical glitch but as a class and property relation: as long as land and labor remain subordinated to capital, the rift widens. Healing it requires the abolition of capitalist property in both agriculture and industry.

The most successful attempts so far have come from societies that broke with capitalist agribusiness and placed land under collective or state control. Cuba’s post-Special Period transition integrated urban food production with rural organic farming, recycling urban organic waste back into peri-urban farms. In China’s “ecological civilization” framework, municipal waste treatment plants have been adapted to recover nutrients for agricultural use, though the depth of this transformation is uneven and contested. In Kerala’s decentralized planning, cooperatives link local markets with small-scale producers, reducing the metabolic distance between production and consumption.

Even under hostile conditions, movements are experimenting. The MST in Brazil has developed agroecological settlements that integrate composting, biogas, and diversified cropping, directly countering the soil depletion of agribusiness soy monocultures. In Zimbabwe, farmer cooperatives have rebuilt soil fertility through community-managed nutrient cycles, despite sanctions and economic sabotage. In these cases, the rift is not just an environmental wound — it is a political battlefield, where the right to control the flow of life’s basic materials is a question of class power.

The reconnection of human and ecological metabolism is not simply “sustainability” — a term capitalism has already commodified. It is about restoring the material basis of human survival on terms that serve the working class and the oppressed, not the profit margins of global capital. It requires integrated planning that treats food, water, waste, and energy not as separate “sectors” but as parts of a unified life system. And it demands that this system be democratically governed by those who depend on it, not by the technocrats of the bourgeois state.

The rift will not heal itself. Either it is closed by revolutionary transformation, or it will be closed by collapse — through soil exhaustion, water scarcity, and climate chaos. In that sense, ecosocialist planning is not just about creating a “greener” society; it is about ensuring there is a society at all.

Part X – Reconnection as Revolution

We began with the simple fact that humanity’s connection to nature has been eroded, commodified, and sold back to us in fragments — a 200-year trajectory in which the ruling class has turned rivers, forests, soils, and skies into raw inputs for profit. Along the way, this theft of connection has been dressed in the language of “progress,” “modernization,” and “development,” masking the reality that alienation from the land is not a cultural accident but a structural necessity of capitalist accumulation. The more disconnected we are, the easier it is for capital to turn the living world into dead commodities and our own labor into disposable waste.

The ecological crisis is not a side effect of capitalism; it is its metabolic truth. Urban overbuild and rural dispossession are two sides of the same coin, as are industrial monocultures and urban food deserts, climate collapse and imperialist resource wars. Each wound inflicted on the earth is mirrored by a wound inflicted on the working class — especially the colonized, whose lands are strip-mined, whose waters are poisoned, and whose children are driven into sweatshops and slums. The alienation of human beings from nature is inseparable from the alienation of workers from the means of production and the alienation of whole nations from their sovereignty.

In the Global South, revolutionary experiments have already shown that reconnection is not a utopian dream but a living possibility. Cuba’s urban gardens, the MST’s agroecological settlements in Brazil, Kerala’s decentralized planning, and Zimbabwe’s cooperative soil restoration efforts are not “green reforms” — they are acts of class struggle waged on ecological terrain. They prove that it is possible to rebuild the metabolic bond between people and the earth when land, water, and labor are taken out of the circuit of private accumulation and placed under collective stewardship.

But let us be clear: the Global North cannot outsource this revolution. The imperial core must break its own dependence on the extraction of Southern resources, dismantle the technofascist structures that manage ecological collapse for profit, and reorient production toward meeting human needs within ecological limits. This means confronting the settler-colonial land regime, abolishing agribusiness monopolies, and transforming cities from concrete prisons into nodes of ecological regeneration.

Reconnection, then, is not an individual lifestyle choice, nor is it reducible to charity-led greening projects. It is a program of revolutionary transformation that seizes control of the material flows of life — food, water, waste, energy, and land — and places them under the democratic control of the people. It is a political economy of repair, where the healing of the soil and the healing of the working class are one and the same process.

We are faced with two futures: one in which the metabolic rift is closed through the planned re-integration of humanity and nature on egalitarian and socialist terms, and another in which it is closed through collapse — by famine, forced migrations, and ecological tipping points beyond return. The ruling class has already chosen the second path. Our task is to force history toward the first.

The struggle for nature is the struggle for socialism. The struggle for socialism is the struggle for life itself. There is no middle ground.

https://weaponizedinformation.wordpress ... om-nature/

******

Eight Pangolin Species Face High Extinction Risk

A pangolin. X/ @PalmOilDetect

August 27, 2025 Hour: 9:26 am

Illegal trade, habitat loss, and lack of updated population data threaten survival despite global protections.

On Wednesday, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) published a report showing that all eight pangolin species face a high risk of extinction due to overexploitation and habitat loss.

The report said illicit trade in pangolins remains widespread and highly organized. The animal was suspected at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic of being the direct transmitter of the virus to humans, but that hypothesis was later set aside in favor of the bat origin theory. Most experts, however, believe that if there was an intermediary host, it has not yet been identified.

Pangolins are considered fully protected species in almost every country and are listed among the animals with the highest degree of protection. Their trade is strictly regulated and limited to very specific circumstances.

Nonetheless, between 2016 and 2024, seizures of pangolin products affected more than half a million animals across 75 countries and 178 trade routes, with pangolin scales accounting for 99% of confiscated parts, the IUCN reported.

Those figures, however, reflect only a fraction of the actual trade, since not all illicit shipments are detected or intercepted by law enforcement. In addition to international trafficking, local demand for pangolin meat and other products persists in many countries. The lack of updated population estimates and limited management in the landscapes where pangolins live also complicate efforts to assess their conservation status.

“Pangolins are one of the most distinctive mammals on Earth and are among the planet’s most extraordinary creatures – ancient, gentle, and irreplaceable. Today, they are under immense pressure due to exploitation and habitat loss. Protecting them is not just about saving a species, but about safeguarding the balance of our ecosystems and the wonder of nature itself. With stronger global cooperation and a united commitment – not only by governments, but across all sectors of society – we can ensure pangolins continue to thrive for generations to come,” IUCN Director Grethel Aguliar said.

“On-going pangolin trafficking and population declines underscore that trade bans and policy changes alone are not enough,” scientist Matthew Shirley said, urging the parties of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) “to work with relevant local and national stakeholders, especially grassroots, community and indigenous organizations, to incentivize effective pangolin conservation.”

“Engaging communities, Indigenous peoples, and even pangolin consumers, to co-design and implement the conservation interventions are powerful bottom-up mechanisms needed to complement the top-down policy prescriptions and achieve the desired outcomes for pangolins,” he added.

https://www.telesurenglish.net/eight-pa ... tion-risk/